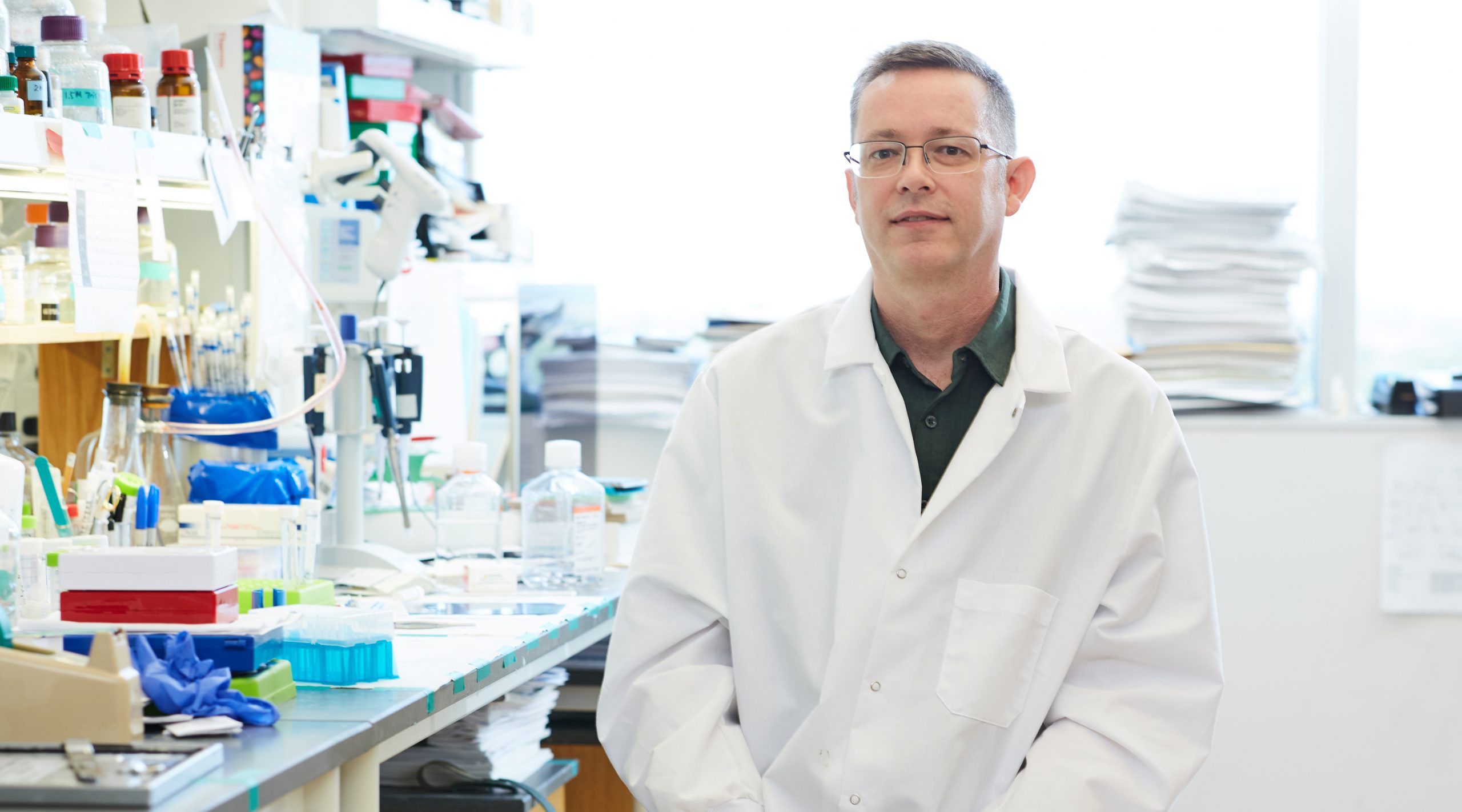

Lorin Olson, Ph.D.

Professor

Cardiovascular Biology Research Program

Scientific Director, Oklahoma Center for Adult Stem Cell Research

My 101

Our bodies have the capacity to repair themselves through an intricate process that closes wounds and returns damaged tissue to a functional state. This process works remarkably well when we are young, but it is prone to interruption as we age. Non-healing chronic wounds commonly occur in the elderly and those who have poor circulation. The opposite of a chronic wound is scar tissue, which occurs when overactive repair processes create excessive new tissue. This is known as fibrosis and it can attack any organ where local stress is not controlled. There is a tremendous need for new technology to solve the medical problems of non-healing wounds and fibrosis, and this can only come through a better understanding of the wound repair process.

Injured or stressed tissues produce a small protein signal called platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF). Some cells have specific PDGF-receptors on the cell surface that allow them to sense the protein signal. PDGF stimulates wound repair, but too much PDGF promotes fibrosis. Therefore, our bodies must maintain a careful balance of PDGF in order to achieve proper tissue repair.

A few cells in the body, called adult stem cells, have great potential to regenerate damaged tissue and influence neighboring cells to support wound repair. Some kinds of adult stem cells have PDGF-receptors. We are still uncovering how PDGF-receptors control adult stem cells, and how aberrant PDGF signaling could promote disease through misregulation of adult stem cells.

The studies in my laboratory are designed to understand how PDGF works in tissue repair and how too much PDGF leads to scar tissue. We focus on a few tissues that are rich in adult stem cells and PDGF: blood vessels, skin, fat, and skeleton. The tissue repair process appears to be similar in mice and humans, in most respects. We use genetically engineered mice with different amounts of PDGF to understand how PDGF might be acting in tissue repair. We can also mark adult stem cells while they are still in the tissue and track their behavior during tissue repair, an approach called lineage tracing. By understanding how tissue repair is regulated by PDGF and adult stem cells, we hope to suggest new therapies for tissue repair and protection from fibrosis.

We are also interested in recently discovered human genetic diseases involving too much PDGF signaling. Penttinen progeria syndrome and Kosaki overgrowth syndrome are caused by gain-of-function mutations in PDGF-receptor beta. These diseases cause connective tissue wasting in young people that resembles accelerated aging, but paradoxically, they sometimes involve connective tissue overgrowth. Do these diseases result from the misregulation of adult stem cells in blood vessels and connective tissues?

Research

The Olson laboratory is interested in how growth factors regulate connective tissue development, homeostasis, and repair. We use genetic mouse models to investigate signaling pathways and target genes by which Platelet Derived Growth Factor Receptor (PDGFR) signaling regulates skin wound healing and bone fracture repair. We are also studying human genetic diseases where hyperactive PDGFR signaling causes connective tissue overgrowth or wasting, depending on cell types and signaling pathways that are still being identified. We also seek to understand the function of mesenchymal progenitor cells that reside in niches around blood vessels throughout the body, and that express combinations of the two vertebrate PDGFRs, PDGFRα and PDGFRβ.

Wound repair:

To heal wounds in the skin, dermal fibroblasts switch from quiescence to an activated state where they migrate, proliferate, and secrete extracellular matrix (ECM) that forms granulation tissue, a temporary tissue that initially fills the wound bed. During this process some fibroblasts acquire a contractile phenotype and become myofibroblasts. Myofibroblasts support healing by generating contractile forces that reduce the size of the wound bed. Precise control of fibroblast activation and myofibroblast differentiation is critical. Too much fibroblast proliferation and ECM secretion leads to expansion of scar tissue and fibrosis, and uncontrolled myofibroblast activity leads to contractures. On the other hand, too little fibroblast activation or contraction contributes to chronic wounds. We are studying wound repair and growth factor-regulated processes in fibroblasts that are involved in granulation tissue formation and contraction. Wound healing involves not only activation and differentiation of fibroblasts, which originate from various local sources, but also the coordinated activities of epidermal, vascular, and immune cells. Growth factors, cytokines, ECMs, and cell-adhesion complexes are critical regulators of the cell behaviors required for wound healing.

We are interested in the receptors for platelet derived growth factor (PDGF), of which there are two, PDGF receptor alpha (PDGFRα) and beta (PDGFRβ). Gain of function studies in the mouse indicate a role for these receptors in the development and homeostasis of connective tissue (Olson & Soriano 2009; Olson & Soriano 2011). PDGFRα gain of function can activate fibroblasts and produce fibrosis while inhibiting progenitor cells from differentiating into adipocytes or myofibroblasts (Iwayama et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2017). This raises the question of whether PDGFRα gain of function would be beneficial for wound healing by increasing fibroblast activation, or whether it would be detrimental by inhibiting differentiation. Both PDGFRs are expressed in granulation tissue fibroblasts, albeit with different kinetics, which raises the question of specialized functions for PDGFRα vs. PDGFRβ. We are currently investigating these questions using a variety of gain of function and loss of function approaches. In the wound healing context, we are also studying the function of PDGF regulated signaling pathways and transcription factors, for instance STAT1, which is strongly activated by gain of function PDGFRβ signaling (He et al., 2015, He et al., 2017) and suppresses myofibroblast differentiation in wound healing (Medley 2020). Most recently, we created new PDGFR knockin mice for intersectional lineage tracing and mosaic mutant analysis (Sun, Sakashita et al., 2020), which will allow further investigation of the role of PDGF signaling in wound repair.

PDGFRβ mutations and human syndromes:

Gain of function PDGF signaling can cause gliomas, sarcomas, and other cancers in humans. However, in mice, gain of function PDGFRβ signaling leads to overexpression of interferon signaling genes (ISGs) and lethal autoinflammation (Olson & Soriano 2011). We showed that this PDGFRβ-driven autoinflammation exacerbates atherosclerosis and is dependent on the transcription factor STAT1 (He et al., 2015). We then showed that deletion of Stat1 could allow mice with gain of function PDGFRβ to survive into young adulthood. Strikingly, these rescued mice developed novel phenotypes involving overgrowth of the dermis and skeleton (He et al., 2017). These results are consistent with STAT1 as a negative regulator of PDGFRβ signaling and a potential genetic modifier for cancer or genetic diseases involving gain of function PDGFRβ. To investigate the cellular origin of the overgrowth phenotypes, which must involve a cell type present postnatally and capable of influencing connective tissue growth during adolescence, we are using several tissue-specific Cre drivers to express gain of function PDGFRβ in mesenchymal progenitor cells of bone and dermis.

Independently from our work, other researchers discovered by exome sequencing that congenital mutations in human PDGFRB lead to gain of function signaling in two very different genetic diseases, Penttinen syndrome (PS) and Kosaki overgrowth syndrome (KS). In PS, a mutation in the PDGFRβ juxtamembrane domain leads to connective tissue wasting with features of progeria. In contrast, the KS mutation alters the PDGFRβ kinase domain and leads to connective tissue overgrowth. Both mutations result in constitutive PDGFRβ signaling and are therefore gain of function, but the strikingly different clinical phenotypes raised the question of whether different signaling pathways might be utilized by different mutants. To us, these discoveries in humans had obvious parallels to the overgrowth and interferon-driven wasting we had characterized in mice (He et al., 2017). We hypothesize that STAT1 and other STAT family proteins are differently activated in PS and KS. Currently we have two new knockin mouse lines with mutation in either the PDGFRβ juxtamembrane domain (like PS) or in the kinase domain (like KS), which we will use to explore these questions.

Mesenchymal progenitor cells in the perivasculature:

PDGFRα and PDGFRβ are expressed by mesenchymal progenitor cells that reside in perivascular niches within the adventitial layer of blood vessels found in most organs of the body. Work from our lab and others has shown that these progenitor cells can differentiate into adipocytes or myofibroblasts, depending on inductive cues in vivo (Iwayama et al., 2015, Sun et al., 2017). Do PDGFRα and PDGFRβ regulate progenitor cell function during postnatal growth, homeostasis, and tissue repair? To answer this question, we have generated knockin-in alleles that allow Cre/lox-mediated mutation of Pdgfra or Pdgfrb with genetically linked Flp/frt-mediated cell labeling. This dual-recombinase system labels single mutant cells and their progeny with a fluorescent reporter, which can be used for genetic mosaic mutant analysis and intersectional lineage tracing. Utilizing this system, we performed lineage labeling to compare the adipogenic potential of Pdgfra and Pdgfrb cell lineages at different developmental and postnatal stages (Sun, Sakashita, et al., 2020). Mosaic mutant analysis of Pdgfra loss of function and Pdgfrb loss of function progenitor cells showed increased adipocyte differentiation, and conversely, Pdgfra gain of function progenitor cells were inhibited from undergoing adipocyte differentiation (Sun, Sakashita, et al., 2020). An important remaining question pertains to how PDGF signaling exerts these effects over progenitor cell fate.

Brief CV

Education

B.S., Brigham Young University, UT, 1996

Ph.D., University of California, San Diego, CA, 2004

Postdoc, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA, 2005-2008

Postdoc, Mt. Sinai School of Medicine, New York City, NY, 2008-2010

Honors and Awards

American Cancer Society Postdoctoral Fellowship, 2007-2009

Best Publication in 2009 Award, Mt. Sinai School of Medicine Office of Postdoctoral Affairs, 2010

Pew Scholar in Biomedical Research, 2012-2016

Springer Junior Investigator Award, North American Vascular Biology Organization, 2012

Fred Jones Award for Scientific Achievement, OMRF, 2013

10th Annual Tucker Collines Lecturer (Boston Children’s Hospital), 2018

Joined OMRF scientific staff in 2010

Publications

Recent Publications

Yang J, Zhu L, Pan H, Ueharu H, Toda M, Yang Q, Hallett SA, Olson LE, Mishina Y. A BMP-controlled metabolic-epigenetic signaling cascade directs midfacial morphogenesis. J Clin Invest, 2024 March, PMID: 38466355, PMCID: PMC11014657

Nandadasa S, O'Donnell A, Murao A, Yamaguchi Y, Midura RJ, Olson L, Apte SS. The versican-hyaluronan complex provides an essential extracellular matrix niche for Flk1(+) hematoendothelial progenitors. Matrix Biol 97:40-57, 2021 March, PMID: 33454424, PMCID: PMC8039968

He X, Cheng R, Park K, Benyajati S, Moiseyev G, Sun C, Olson LE, Yang Y, Eby BK, Lau K, Ma JX. Pigment epithelium-derived factor, a noninhibitory serine protease inhibitor, is renoprotective by inhibiting the Wnt pathway. Kidney Int 91:642-657, 2017 March, PMID: 27914705, PMCID: PMC5313326

Selected Publications

Sun C, Sakashita H, Kim J, Tang Z, Upchurch GM, Yao L, Berry WL, Griffin TM, Olson LE. Mosaic Mutant Analysis Identifies PDGFRα/PDGFRβ as Negative Regulators of Adipogenesis. Cell Stem Cell. 2020 May 7;26(5):707-721.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2020.03.004. Epub 2020 Mar 30. PMID: 32229310, PMCID: PMC7214206.

Medley SC, Rathnakar BH, Georgescu C, Wren JD, Olson LE. Fibroblast-specific Stat1 deletion enhances the myofibroblast phenotype during tissue repair. Wound Repair Regen. 2020 Jul;28(4):448-459. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12807. Epub 2020 Mar 24. PMID: 32175700, PMCID: PMC7321860

Sun C, Berry WL, Olson LE. PDGFRα controls the balance of stromal and adipogenic cells during adipose tissue organogenesis. Development 2017 Jan 1;144(1):83-94. PMID: 28049691, PMCID: PMC5278626

He C, Medley SC, Kim J, Sun C, Kwon HR, Sakashita H, Pincu Y, Yao L, Eppard D, Dai B, Berry WL, Griffin TM, Olson LE. STAT1 modulates tissue wasting or overgrowth downstream of PDGFRβ. Genes Dev. 2017 Aug 15;31(16)1666-16678. PMID: 28924035, PMCID: PMC5647937

He C, Medley SC, Hu T, Hinsdale ME, Lupu F, Virmani R, Olson LE. PDGFRβ signalling regulates local inflammation and synergizes with hypercholesterolaemia to promote atherosclerosis. Nat Commun. 2015 Jul 17;6:7770. PMID: 26183159, PMCID: PMC4507293

Iwayama T, Steele C, Yao L, Dozmorov MG, Karamichos D, Wren JD, Olson LE. PDGFRα signaling drives adipose tissue fibrosis by targeting progenitor cell plasticity. Genes Dev. 2015 Jun 1;29(11):1106-19. PMID: 26019175, PMCID: PMC4470280

Contact

Cardiovascular Biology Research Program, MS 45

Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation

825 NE 13th Street, Oklahoma City, OK 73104

Phone: (405) 271-7535; (405) 271-7390

Fax: (405) 271-7417

E-mail: Lorin-Olson@omrf.org

For media inquiries, please contact OMRF’s Office of Public Affairs at news@omrf.org.

Lab Staff

Longbiao Yao, M.D.

Staff Scientist

Hae Ryong Kwon, Ph.D.

Research Assistant Professor

Bharath Holenarasipura Rathnakar, Ph.D.

Postdoctoral Scientist

Sunhye Jeong, Ph.D.

Postdoctoral Scientist

Alex Rackley

Research Technician IV

Jang Kim, Ph.D.

Graduate Student

John Woods

Graduate Student

Grace Hammonds

Administrative Assistant II

News from the Olson lab

July A pair of OMRF scientists take a different approach to the study of healing. Time, it’s said, heals all wounds. But we all know that’s not quite true. “Everything must work just right for proper wound healing to take place,” says OMRF’s Dr. Lorin Olson. “It’s a delicate balance.” Olson studies a compound in the […]