I first learned about the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation a few years after I arrived in Oklahoma. I’d received a freelance writing assignment from Oklahoma Today magazine, and my editor tasked me with writing a profile of Dr. Jordan Tang.

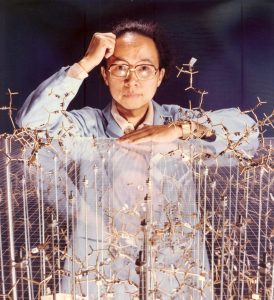

Tang had recently discovered the enzyme believed responsible for Alzheimer’s disease, cloned the enzyme, and then developed an experimental inhibitor that stopped the enzyme. When I sat with Dr. Tang in his office overlooking Northeast 13th Street, he explained the mind-bogglingly complicated work using metaphors that even I, an attorney and English major, could understand. The enzyme, he said, was like a Pac-Man that cut proteins, and he and his OMRF research team had invented a chemical chewing gum that would stop the waka-waka-waka.

“These are monumental discoveries,” Dr. J. Donald Capra, then OMRF’s president, told me when I interviewed him for the article. “I will be stunned if a decade from now, corner drugstores are not selling a drug to inhibit Alzheimer’s disease that came out of this foundation.”

That was twenty years ago. And, as anyone reading this column knows, despite Dr. Tang’s best efforts, Alzheimer’s remains a disease without an effective treatment.

But this is not a story about failure. In fact, it’s quite the opposite.

This weekend marks the 75th anniversary of the day in 1946 when Oklahoma’s Secretary of State signed OMRF’s charter. The articles of incorporation set forth, in lawyerly language, a charge that was both simple and daunting: “conducting scientific investigations in medicine.”

Over the ensuing three-quarters of a century, OMRF researchers have done just that. And, for a relatively small place – OMRF employs a bit under 500 employees in total, whereas a major academic medical center like Harvard Medical School counts 12,000 faculty members alone – the foundation has punched well above its weight.

Today, health care providers around the world use three different lifesaving drugs born at OMRF to help patients. Soliris and Ceprotin treat life-threatening blood disorders and a debilitating neurological disease. And Adakveo, now approved in the U.S. and 43 other countries, is the first targeted therapy approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for sickle cell disease, a debilitating and potentially fatal condition that affects an estimated 100,000 Americans, most of African descent.

OMRF has also become a national and international leader in the quest to understand, manage and prevent autoimmune diseases. Foundation scientists have helped identify and confirm more than 60 genes tied to lupus. They’ve assembled a world-renowned collection of biological samples from patients and their families that researchers from across the globe have tapped for hundreds of studies. Their work also gave birth to Vectra DA, a disease management test used by rheumatologists everywhere to help guide the care of patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Medical research is, by nature, experimental. And not every experiment that OMRF scientists performed has succeeded. Far from it. But that’s okay.

As we’ve been reminded time and again during the pandemic, science is an iterative process. We think we know things, but until researchers have had time to kick the tires – from every angle and over a prolonged period – we can’t tell for sure. And even what we thought we knew a month, a year or a decade ago may turn out to be wrong. Or at least different.

Like nature itself, science requires constant adaptation. Observation and creativity are crucial to the process, but so is a willingness to change course when a hypothesis proves faulty. When an experiment fails.

Dr. Tang passed away last year at the age of 89. He spent more than 50 of those years at OMRF. And while he never reached that holy grail of an Alzheimer’s drug, his work pushed the field forward significantly. Many of the experimental treatments currently in development rely upon insights that Dr. Tang and his research team made.

Dr. Tang’s spirit also lives on in protease inhibition drugs that transformed the therapeutic landscape for patients with HIV and AIDS. His expertise provided pharmaceutical companies with a key element in overcoming drug resistance in treatments for the deadly disease. Now, when taken in combination with other antiretroviral drugs, protease inhibitors add decades to the lives of people with HIV and AIDS, decreasing viral loads to undetectable levels and allowing patients to effectively manage and live with the disease.

That’s quite a legacy.

As we blow out the candles on OMRF’s first 75 years, it’s worth remembering the words of Sir Alexander Fleming, the British physician-researcher who discovered penicillin. When he spoke at OMRF’s dedication, he wondered what the future would hold for the young foundation.

“You might call it a frightful gamble, just as it is a gamble when a baby is born into this world, or when a bore is sunk for oil,” he said. “But the results of the work done here may prove a thousand times more valuable to humanity than all the oil in Oklahoma.”

Has OMRF has yet met that lofty charge? At the very least, our scientists have already made a good dent. And unlike a human being who’s been around for the better part of a century, a 75-year-old research institute can look to the future and confidently say the best is yet to come.

—

Adam Cohen is OMRF’s senior vice president & general counsel and interim president. He can be reached at contact@omrf.org. Get On Your Health delivered to your inbox each Sunday — sign up here.