Most of us know someone, or are someone, who has heart disease. It causes more deaths in the U.S. than cancer, taking 600,000 lives each year and millions more worldwide.

One of the most common forms of heart disease is aortic stenosis. It occurs when the main valve of the heart — the aortic valve — becomes stenotic or narrowed. The narrowing of the valve overworks the heart, eventually leading to heart failure or even sudden death.

According to the American Heart Association, aortic stenosis affects more than 20% of older Americans. In addition to causing heart failure, research studies have also linked it to a higher risk for complications and severe illness with viruses like Covid-19.

According to the American Heart Association, aortic stenosis affects more than 20% of older Americans. In addition to causing heart failure, research studies have also linked it to a higher risk for complications and severe illness with viruses like Covid-19.

The only approved treatment for advanced cases of aortic stenosis is an invasive, risky valve replacement surgery. But Dr. Jasimuddin Ahamed aims to change that.

In his lab at OMRF, Ahamed studies how fibrosis, the formation of scar tissue, can damage the heart. He and his research team discovered that a particular naturally occurring protein contributes to scar tissue formation in the aortic valve, leading to stenosis. This finding suggests that targeting this protein with a drug could potentially treat or prevent the condition.

“Once aortic stenosis is fully developed, little to nothing can be done,” says Ahamed, who joined OMRF in 2015 from Rockefeller University in New York City. “But early intervention with a new drug might halt its progression and keep the heart working as it should.”

Using specially engineered mice that mimic the symptoms of aortic stenosis in its earliest stages, Ahamed is testing drugs to do just that.

The work has attracted the attention of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, which in 2020 awarded Ahamed a four-year grant to support the research. “This could result in a major breakthrough in heart health for our aging population,” says Ahamed.

He’ll utilize a method he’s developed to test compounds that could halt the disease process. “Our new, highly predictive experimental model can be used to test drugs to prevent the progression of this disease by targeting it in its initial stages,” says Ahamed.

Still, progress takes time. And any experimental compound, even a promising one, faces long odds of reaching the clinic.

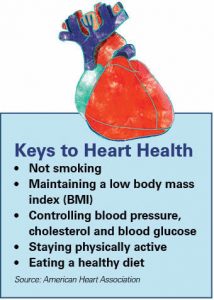

All of which reminds us to focus on those elements of heart health we can control. “Especially over the last year, many of us have become less physically active and slacked on healthy eating,” says Dr. Stephen Prescott, OMRF’s president and a cardiologist.

He recommends small changes, like regular walks and a diet heavy in vegetables, whole grains and lean proteins. And that’s important, because if we take care of our hearts, they should beat more than 2.5 billion times in our lives.

Illustration by John Jay Cabuay

—

Read more from OMRF’s 2020 Annual Report

A Year of Challenges

New Hope for Treating Vision Loss

A Homecoming of Sorts

Honoring a Recovered Texan

An Anti-Aging Pill?

Old Drug, New Tricks

From Bedside to Bench

How 2020 Changed Science