10:00

The LCD numerals on the face of the countdown timer reminded me of the clock by my bed. Jackie Keyser, a nurse at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, set the little, white rectangle down in front of me and hit the start button.

In less than 10 minutes, I’d know if I still had antibodies to Covid-19.

9:59, 9:58, 9:57…

Exactly six months earlier, I’d received my second shot of what was either the Pfizer/BioNTech Covid-19 vaccine or a placebo. The study was blinded, meaning I had no idea which I’d received.

At OMRF, Dr. Judith James had been kind enough to enroll me in an antibody study she and her research team were doing. Everyone else in the study had recovered from Covid-19, so she was investigating what kind of immune responses their bodies made following infection.

I, on the other hand, had not to my knowledge been infected. So, if testing showed that I possessed antibodies, it likely meant that I’d received the actual vaccine rather than a placebo.

And when Jackie first tested me at the end of September, I did show antibodies to Covid-19. Specifically, I had what’s known as immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies, which offer long-term protection against infection.

I was, of course, ecstatic.

7:34, 7:33…

I stared at the little antibody test as the timer counted down. It looked like a pregnancy test, only it had a drop of my blood in one window. My eyes were fixed on the other window, where I tried to discern a line in the midst of a pink square.

Nothing.

When I got my two shots late last summer, no one knew whether any of the then-experimental vaccines would work. Or if they’d produce dangerous side effects.

I’d decided to participate in the trials because after many months of feeling powerless and frozen in the face of the pandemic, here was something, however small, I could do to help end it.

And the vaccines have proven effective, beyond just about any scientist’s wildest dreams. In both the trials and subsequent real-world studies, they’ve offered robust protection against the virus, particularly severe illness. They’ve also shown themselves extremely safe, producing only garden-variety aches and pains in the vast majority of those who experience any side effects at all.

5:07, 5:06…

Still no line.

Based on my early antibody test results, I felt almost certain I’d received the real McCoy in the trial. My suspicion was finally confirmed in February, when Pfizer “unblinded” me.

Still, I continue to participate in the trials. Each week, I complete a report of whether I’ve experienced symptoms. (I haven’t.) Periodically, I also return to the trial site for blood work. (Those results aren’t shared with me.)

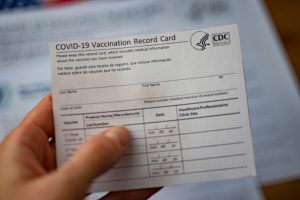

When I went to the trial site earlier this month, at the end of my visit, the trial coordinator presented me with my vaccination card. While I’d long suspected I’d been vaccinated, holding that physical proof in my hand – even if it was just a slip of paper – made me feel like I might float away for a moment.

“I’ve really found this whole experience of being a guinea pig great,” I said, my mask not managing to conceal a big grin.

The coordinator frowned. “You’re not a guinea pig. Guinea pigs don’t have a choice,” she said. “You’re a volunteer.”

“Yes, I’m a volunteer,” I nodded, trying to look chastened. But I’m pretty sure I was still smiling.

3:48, 3:47…

Could that be a faint line? I blinked. Tough to tell how much I was seeing, how much I was imagining.

As Dr. James’ research study at OMRF progressed, her team became more interested in my results. I was the first person in the study to receive the vaccine (they later enrolled others), so I’d become something of a canary in a coal mine.

In other words, the longer the vaccine conferred immunity for me, the better it bodes for everyone else who gets vaccinated.

Dr. Jay Wohlgemuth, chief medical officer at Quest Diagnostics (and my former brother-in-law), reminded me that there are other forms of immunity that will protect us even after antibodies fade. That immunity, though, can’t be tested easily. “So,” he said, “it’s reassuring to see those antibodies.”

2:26, 2:25…

Yup. No mistaking it. That was a line.

Jackie took a look. “It sure is,” she said.

Six months after my last shot, I still had antibodies.

With cases and hospitalizations dropping and the vaccine rollout in full swing, it’s easy to feel like we’ve reached the finish line. But for every Texas-has-reopened-for-business story, there continue to be stark reminders that we’re still fighting a deadly pandemic.

For my girlfriend, the most recent came when a dear friend died of Covid-19 pneumonia last week. He was 48 and left behind a wife and three children, aged 6 to 14.

For him, the vaccine rollout comes too late. But for the rest of us, there is hope.

In the meantime, as we work toward vaccinating enough of our population to achieve herd immunity, the steps we take forward should be measured and slow. Especially with the new variants circulating, we want to ensure we’re protected before we tear off our masks and crowd into restaurants, bars and sporting events.

0:00

0:00

Jackie started to pick up the antibody test. Then she stopped.

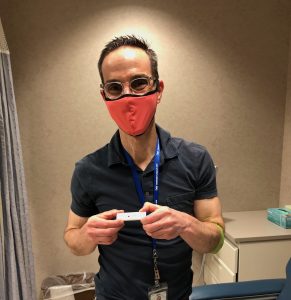

“Some people like me to take a picture of them with their results,” she said. “Would you?”

Even though the pink line had grown a bit more pronounced in the last few minutes, it wasn’t much to look at. But it symbolized so much. The power of science. The resilience of the human spirit. The brighter days that lie ahead.

“Yes, I’d like that,” I said. And when Jackie snapped the photo, I think you could tell I was smiling beneath my mask.

__

Missed the beginning of this series?

Becoming a coronavirus vaccine guinea pig

My life as a vaccine guinea pig, part II

My life as a vaccine guinea pig, part III

Adam Cohen is OMRF’s senior vice president and general counsel. He can be reached at contact@omrf.org. Get On Your Health delivered to your inbox each Sunday — sign up here.