How would your life change if you were immune?

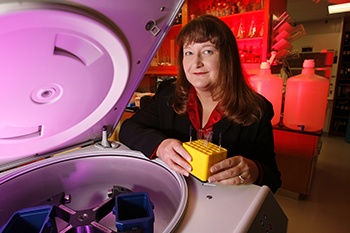

That was a question I asked myself as I awaited the result of my Covid-19 antibody test. The nurse had just pricked my finger. She compressed its tip, raising a pinhead-sized bubble the hue of a maraschino cherry. She then used a small capillary tube to suck up the blood and deposit it onto a window at the center of what’s known as a lateral flow assay.

“It’s like a pregnancy test,” the nurse said. And, indeed, the rectangular plastic box bore more than a passing resemblance to that product that has made countless people squirm in anticipation, its chemicals working like some biopharmaceutical Magic 8 Ball.

I knew the future held no babies for me. But the results of this test might have a similarly profound effect on my future.

In August, I enrolled in the final phase of the Covid-19 vaccine trial sponsored by drugmakers Pfizer and BioNTech. As a result, I am now one of the tens of thousands of people who’ve received a pair of booster shots that contained either doses of an experimental vaccine or squirts of saline solution.

The problem is, I didn’t know which.

After both shots, my arm had grown sore, and I’d developed a headache, a slight sore throat and general fatigue. Or so I thought.

In 18 years of working at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, I’ve learned I have a strong predisposition toward what’s known as medical student syndrome. This psychological phenomenon happens when a person who reads up on a disease comes to believe they suffer from it.

Here, I’d pored over accounts of those who’d experienced short-term side effects of the experimental vaccine: pain at the injection site, minor flu-like symptoms. I certainly didn’t put it past my brain to make me believe I’d felt these sensations, especially because the phenomena people reported were far from black and white.

When I asked Dr. Judith James, an immunologist and OMRF’s Vice President of Clinical Affairs, whether a shot of salt and water could also produce these symptoms, she demurred. “Everything you’re describing could be your immune system kicking into gear in response to the vaccine. But without testing, it’s impossible to know.”

On my follow-up visit, the clinical trials coordinator told me they’d be taking a couple of vials of blood to analyze. I perked up. “For antibodies?”

She nodded.

“Will I find out the results?”

She shook her head. “No, at least not until the study is over” – another two years.

So, I decided to arrange for an independent antibody test. If the results were negative, it meant I’d gotten the placebo, or my body hadn’t formed an immune response to the vaccine. Either way, I’d know I wasn’t protected against future infection. And that the pandemic life I’d come to know would continue.

At the antibody testing site, I did my best to gird for this outcome. As we awaited the results of my assay – “These things take a few minutes,” the nurse said – she explained that even in people who’ve experienced symptoms consistent with Covid-19, most tests come back negative.

I, however, turned out to be one of the lucky ones. My test revealed immunoglobulin G (or IgG) antibodies, which signal long-lasting protection against viral infection.

I nearly broke out skipping. In the clinical trial, I had received the real McCoy. And it had worked. From an immunological perspective, I looked just like someone who’d been infected with the virus and now was, presumably, immune.

This would be my get-out-of-jail-free card. And before long, with FDA approval and widespread vaccination, it would be all of our get-out-of-jail-free cards.

But, of course, the reality is murkier.

“Unfortunately, we don’t yet understand what an immune response to Covid-19 means,” said Dr. Stephen Prescott, OMRF’s president. “We don’t know whether it confers total protection. We also don’t know how long it lasts.”

Still, he explained, based on our experience with other viruses, “if we don’t enjoy complete immunity, there’s nevertheless a good chance it will blunt the force of future infections,” making them milder.

As I write this, I’m awaiting the results of a confirmatory test. (As you may recall, antibody tests have been plagued by false positives.) Regardless of the outcome, though, my life won’t change much, at least in the short term.

I’ll keep wearing my mask. I’ll continue to social distance, wash my hands and avoid spending sustained amounts of time indoors with others.

Do I believe the vaccine worked? Yes, I do. And that belief gives me great comfort, both for myself and for what it means for all of us.

But belief is the operative word here. Unless and until it becomes knowledge, I’ll behave as if I’m still at risk, and still a risk to others.

That last part is the important one. Because I could live with the consequences of my own behavior. But getting someone else sick because of my recklessness? That’s a weight none of us should ever bear.

__

Read the rest of this series

Becoming a coronavirus vaccine guinea pig

You’re here: My life as a vaccine guinea pig, part II

My life as a vaccine guinea pig, part III

My life as a vaccine guinea pig, continued

Adam Cohen is OMRF’s senior vice president and general counsel. He can be reached at contact@omrf.org. Get On Your Health delivered to your inbox each Sunday — sign up here.