New findings from OMRF have revealed clues that could lead to new strategies to combat age-related muscle loss.

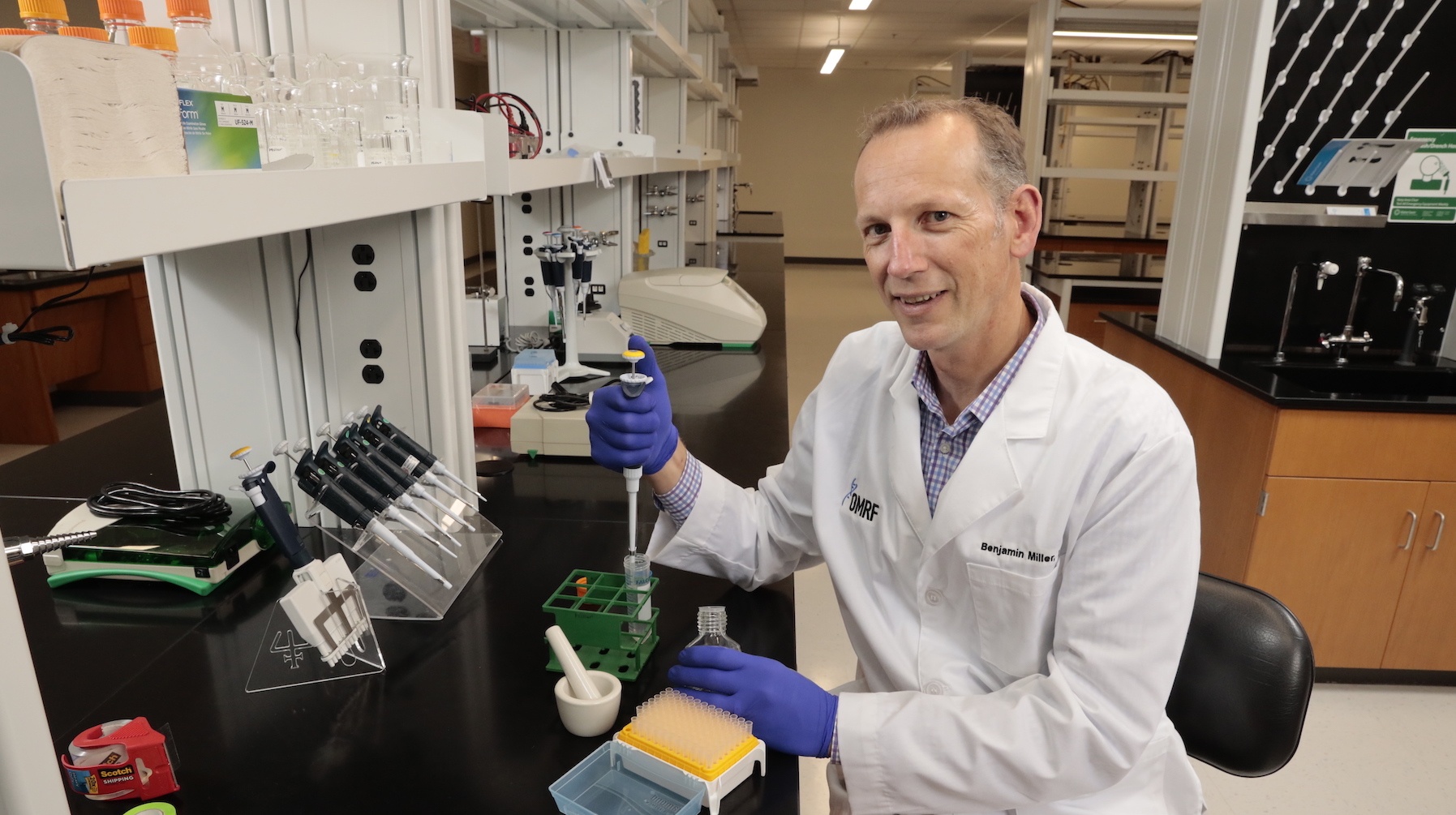

The study was led by OMRF scientist Benjamin Miller, Ph.D., and researchers from the University of Iowa. The biggest breakthrough came from identifying an age where the ability to regrow muscle after a period of loss is greatly impaired. Further, they show that these changes vary by muscle and not all muscles are the same.

The researchers looked at rats and found they could regrow muscle after a period of loss until 24 months of age, but at 28 months this ability dropped off. Miller said this translates to humans in their 70s.

The goal of the study was to better understand the two trajectories by which people lose muscle over time. The first occurs through the gradual loss of muscle that comes with aging. The second results from acute periods of loss that take place after situations like bedrest or following an injury. A better understanding of these two courses could lead to intervention strategies and treatment options.

“The gradual loss over time is something we all go through, but these other critical periods when you are bedridden that can have long-lasting consequences. You can lose muscle mass really quickly during periods of immobilization,” said Miller, a physiologist in OMRF’s Aging and Metabolism Research Program. “Young people have the ability to gain that back quite well, but this seems to be impaired in older individuals.”

This inability to regain muscle sets older people on a new trajectory of loss because they can never really rebound. This can be catastrophic for the elderly, leading to a loss of mobility and independence that often cannot be recaptured.

“Our lab is focused on learning how to maintain muscle, which is critical for maintaining independence and a healthy metabolism,” said Miller. “We want to keep people able-bodied for longer so they can get the most out of their years. This research will give us new targets to aim for toward this goal.”

The second significant finding was that changes with age or from atrophy differ from muscle to muscle. Miller said the results led to additional questions about the underlying mechanisms by which some muscles are maintained during aging, while others are not.

“From a public health perspective, this broadens our knowledge and shows us we need to consider muscles on a case-by-case basis,” said Miller. “This also identifies a critical period where, if someone has an extended period of inactivity, we need to target the regrowth and learn what we can do to intervene.”

The findings were published in the Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle. OMRF scientists Justin Reid and Rick Peelor contributed to the research.