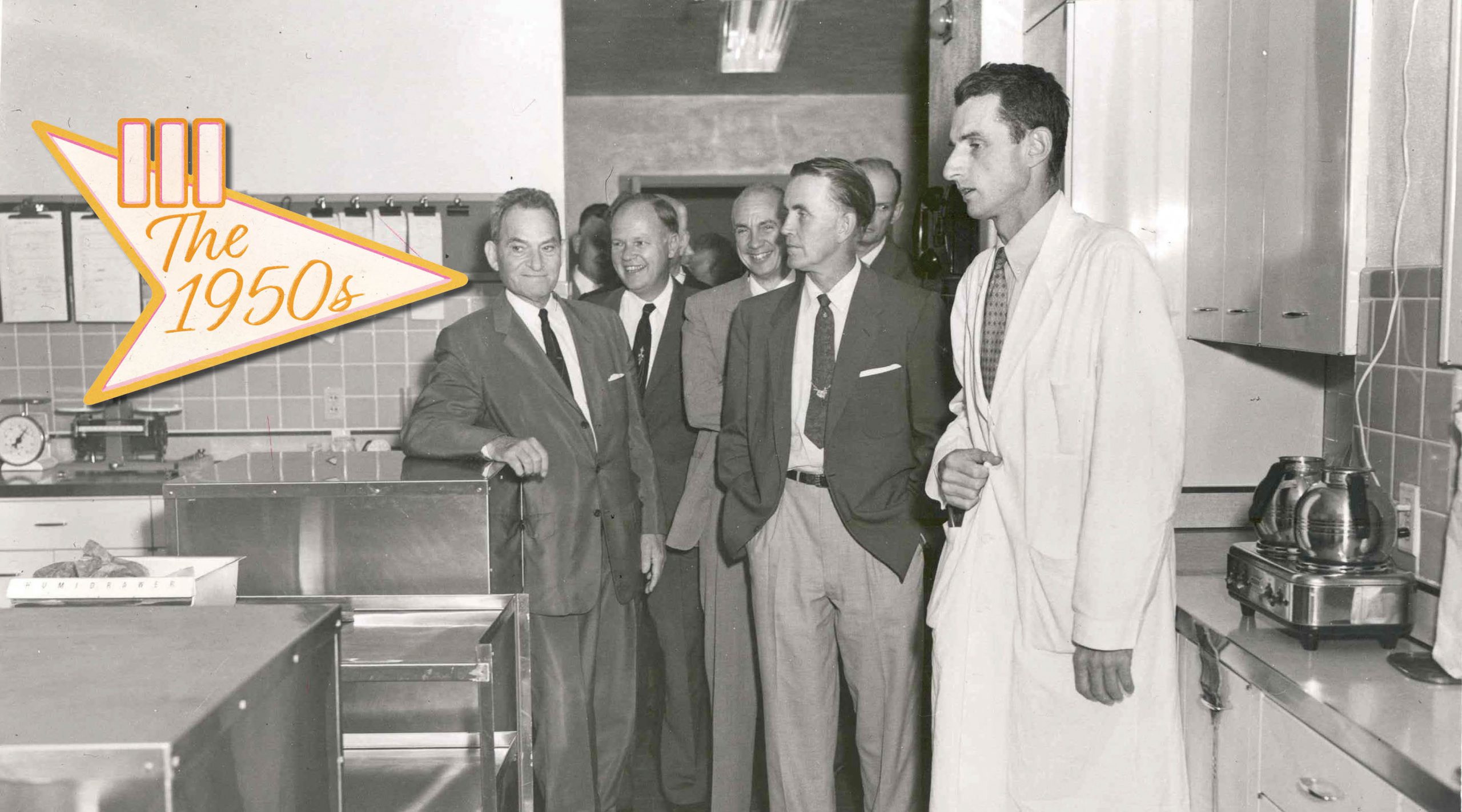

Construction of OMRF’s first research labs wrapped up in the fall of 1950, and the foundation christened the facility with an open house that welcomed 4,000 visitors.

“Areas drawing particular interest included the system of tunnels, the radio-isotope laboratory, the controlled temperature lab, a display of scientific equipment, the animal wing and its first ‘occupants,’ a colony of white rats,” crowed an early OMRF newsletter. Visitors “were interested in the new lobby furniture and draperies, as well as the modern architecture in the lobby.”

The building initially housed 11 laboratories and administrative offices, along with a floor of shelled space for eventual expansion. Within the next year, thanks to a grant from the National Institutes of Health, OMRF opened a 16-bed research hospital.

The foundation recruited researchers from throughout the U.S. – and beyond. OMRF “is contributing mightily to the medical sciences of the world,” explained a fundraising proposal, “not only in productive research but in the training of devoted young men and women from countries around the world who are dedicating their lives to medical research.” An accompanying photo showed scientists from Argentina, Jordan, Denmark, Iran and, from China, a pair of laboratory technicians: Kuen Tang and her husband, Jordan, who would go on to become perhaps the best-known and best-loved scientist in the foundation’s history.

Research initiatives first specialized in cancer, heart disease and metabolic disorders, the program that hired Dr. Mary Carpenter as OMRF’s first female principal investigator in 1954. These “basic” research programs paired with clinical studies in the research hospital, where nurses and physicians treated some of Oklahoma’s sickest patients with experimental therapies. Soon, the research hospital became internationally recognized for its work with childhood cancers.

“I was a patient in your research hospital as a teenager in the 1950s,” wrote Huguette White in 2005, “and I wanted to tell you that I still consider OMRF to be my home.” A native of Lebanon, White traveled to the foundation for treatment of her Ewing’s sarcoma, a rare and deadly bone cancer. “I know I wouldn’t be here now if OMRF hadn’t been there to take care of me.”

‘I watched them build this building.’

“My parents had seven sons, followed by seven daughters. I was born on our farm outside Stroud, the baby of the family – the number 14 child. Mama called me ‘the last button on Gabriel’s coat.’

I watched them build this building. ‘Lord,’ I said, ‘send me somewhere that I can keep my temper.’ And He sent me here.

My first day of work at OMRF was September 16, 1952, in the research hospital. I brought the patients their meals from University Hospital on a cart through the tunnel under 13th Street. We had about 20 employees when I came to work here. And they all wanted to be in charge.

OMRF was segregated in the ’50s. It was a reflection of the times. The Black employees weren’t allowed to participate in parties. We had to eat at a different time than the white employees in the cafeteria. That gradually changed, but I still remember it well.

We always had a Christmas tree in the clinic for the patients and staff. Every year I’d crawl under that tree and peek at my gift. One year while I was under there, the tree fell on me. I was yelling, ‘Help me, help me!’ and everybody came running. So, I got found out!

My first paycheck was for $125. I thought I was rich. I had never been paid more than $90 a month before that. It would go a long way in those days.

My favorite memory would be my patients. I loved them. I cried when they closed the hospital like it was mine.”

Janet Lawrence (front row, left)

OMRF employee, 1952-2005

Condensed from a 2005 interview

—

Read more from this issue of Findings

1940s: A Dream Becomes Reality

1950s: Opening the Doors

1960s: All Hands on Deck

1970s: Finding Firm Footing

1980s: A Time of Growth

1990s: Making A Mark

2000s: Eureka Moments

2010s: Research on the Rise

2020s: A Promising Future