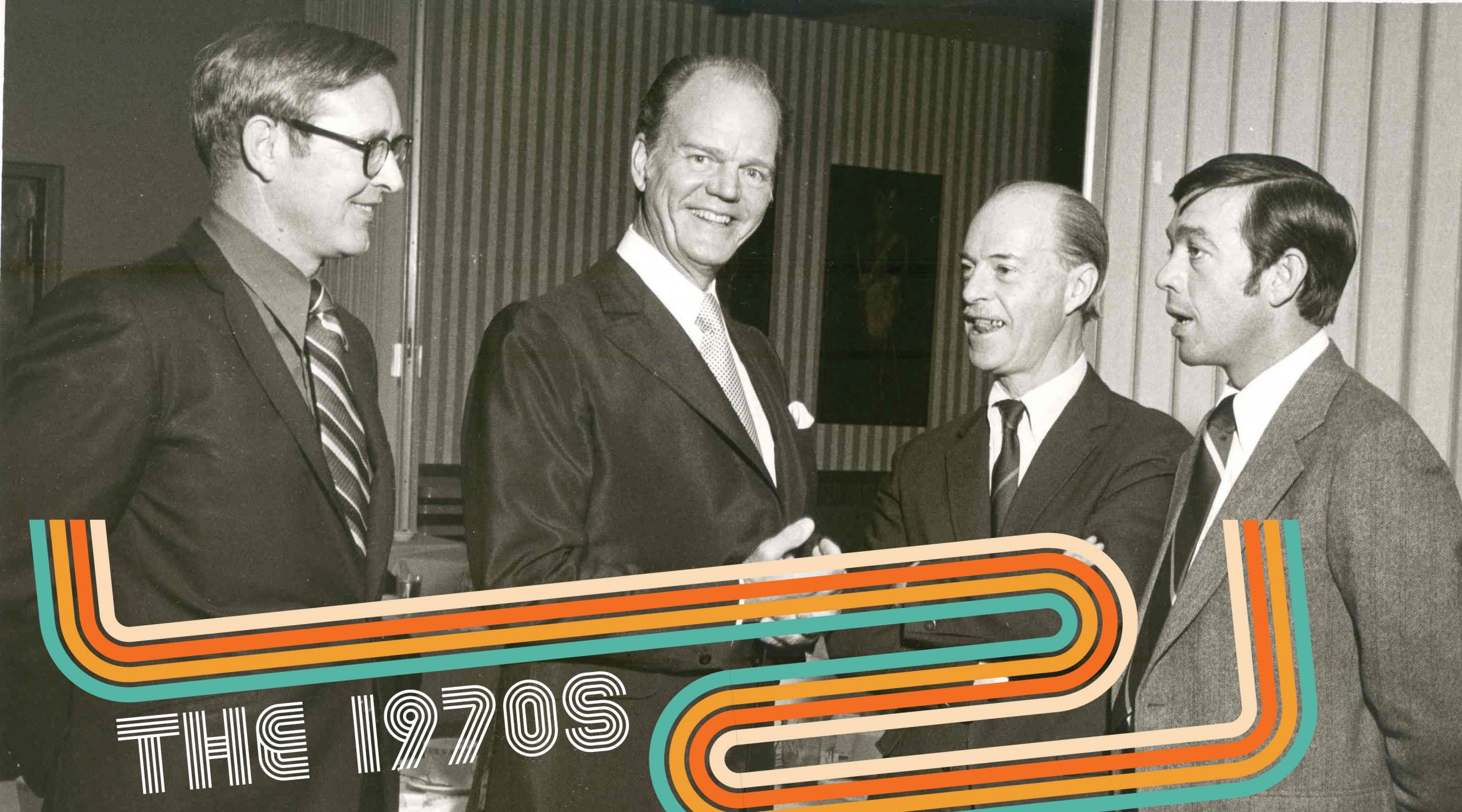

Twenty-six years after he co-authored a paper identifying DNA as the “transforming principle” that determines specific characteristics in the course of human reproduction, Dr. Colin MacLeod became OMRF’s first full-time president in 1970.

Up until that time, representatives from OMRF’s board of directors – who also held day jobs as businesspeople and attorneys – served as president, while day-to-day management of the foundation fell to administrative staff and a research director. However, with OMRF now grown to 300 employees, the time was right to shift to a different model.

A former scientific advisor to both Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, MacLeod brought a resumé the likes of which Oklahoma had never seen. His seminal work on DNA came in 1944, paving the way for Drs. James Watson and Francis Crick to identify the molecule’s structure nine years later. The journal Nature and many others contended MacLeod should have shared in Watson and Crick’s subsequent Nobel Prize, but MacLeod shrugged off the slight. “You know, they make too big a fuss out of that,” he once told a young colleague at OMRF. “The most important thing is we did the work right.”

Unfortunately, only 18 months into his tenure at OMRF, MacLeod died, suffering a heart attack while traveling on foundation business. Still, his leadership and scientific profile helped lay the groundwork for success and stability at OMRF in the ensuing decade.

Another key factor to setting the foundation on a sustainable path were watershed donations from James and Leta Chapman of Tulsa. When Leta died in 1973, it triggered annual distributions to OMRF from the last of a trio of perpetual trusts the couple had established for the benefit of the foundation and a handful of other charities. As of 2021, payments to OMRF from those trusts totaled more than $300 million.

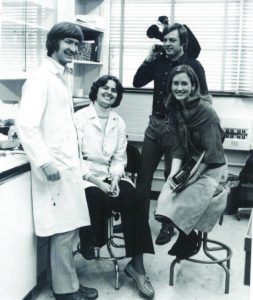

In 1978, NASA selected Dr. Shannon Lucid, then a post-doctoral researcher at OMRF, as a member of its first class of female astronauts in the space shuttle program. Seven years later, she became the sixth woman to reach space, where she’d ultimately log 5,354 hours, a mark that stood for American astronauts until 2007. As a mission specialist, Lucid performed experiments of all kinds. One carried particular echoes of her earthbound days at the foundation.

“On the Columbia, we had 48 rats to tend, and I worked with them every day,” she remembered. She was “a natural for the task,” she said. “I had the experience of doing similar work in the lab at OMRF.”

‘I have finished! I have finished!’

“I jumped out of bed, put on my clothes, and drove to my lab. It was 7:00 when I started to calculate all the data again. By 10:00, I knew I had finally finished. After seven years of working on this project, it was a wonderful feeling. In the whole world, I was the only person who knew the amino acid sequence of the stomach acid pepsin.

I put away my things and started to go home. It was Sunday morning. The hallways were dark, and the building seemed deserted. As I came to the lobby, the head nurse of the OMRF hospital came out from the east wing.

I had seen her a few times and did not know her name. But she was the first human being I saw after I had finished the project. In a moment of excitement, I yelled to her, ‘I have finished! I have finished!’

Then I gave her a hug and ran out of the building.”

Dr. Jordan Tang, 2019

Condensed from his autobiography, “Searching for Rainbows”

—

Read more from this issue of Findings

1940s: A Dream Becomes Reality

1950s: Opening the Doors

1960s: All Hands on Deck

1970s: Finding Firm Footing

1980s: A Time of Growth

1990s: Making A Mark

2000s: Eureka Moments

2010s: Research on the Rise

2020s: A Promising Future