OMRF kicked off the 1960s with a liberating milestone, retiring the mortgage for construction of the foundation.

Tulsa oilman and philanthropist John Mabee donated $150,000 to pay off the debt. That major gift would prove the first of many from the fortunes of Mabee and his wife, Lottie, whose namesake foundation has since donated more than $4.8 million to brick-and-mortar projects at OMRF.

Despite the retirement of OMRF’s initial mortgage, the 1960s dawned with no shortage of financial uncertainty for the young foundation. With OMRF having grown to 140 employees, Executive Vice President Hugh Payne reported to the board of directors that “by the skin of our teeth, we are making the payroll and paying invoices.” Thanks to studies in breast cancer and leukemia, cholesterol, and the effects of stress on any number of physical conditions, OMRF scientists were now securing competitive research grants from the National Institutes of Health, American Cancer Society, American Heart Association and other funders. But these grants only covered a portion of OMRF’s operating costs, which now totaled almost $1 million annually. This left Payne and his staff to raise the balance through a series of campaigns targeted to different professions – bankers, dentists, nurses, physicians and pharmacists – as well as broader initiatives throughout the state.

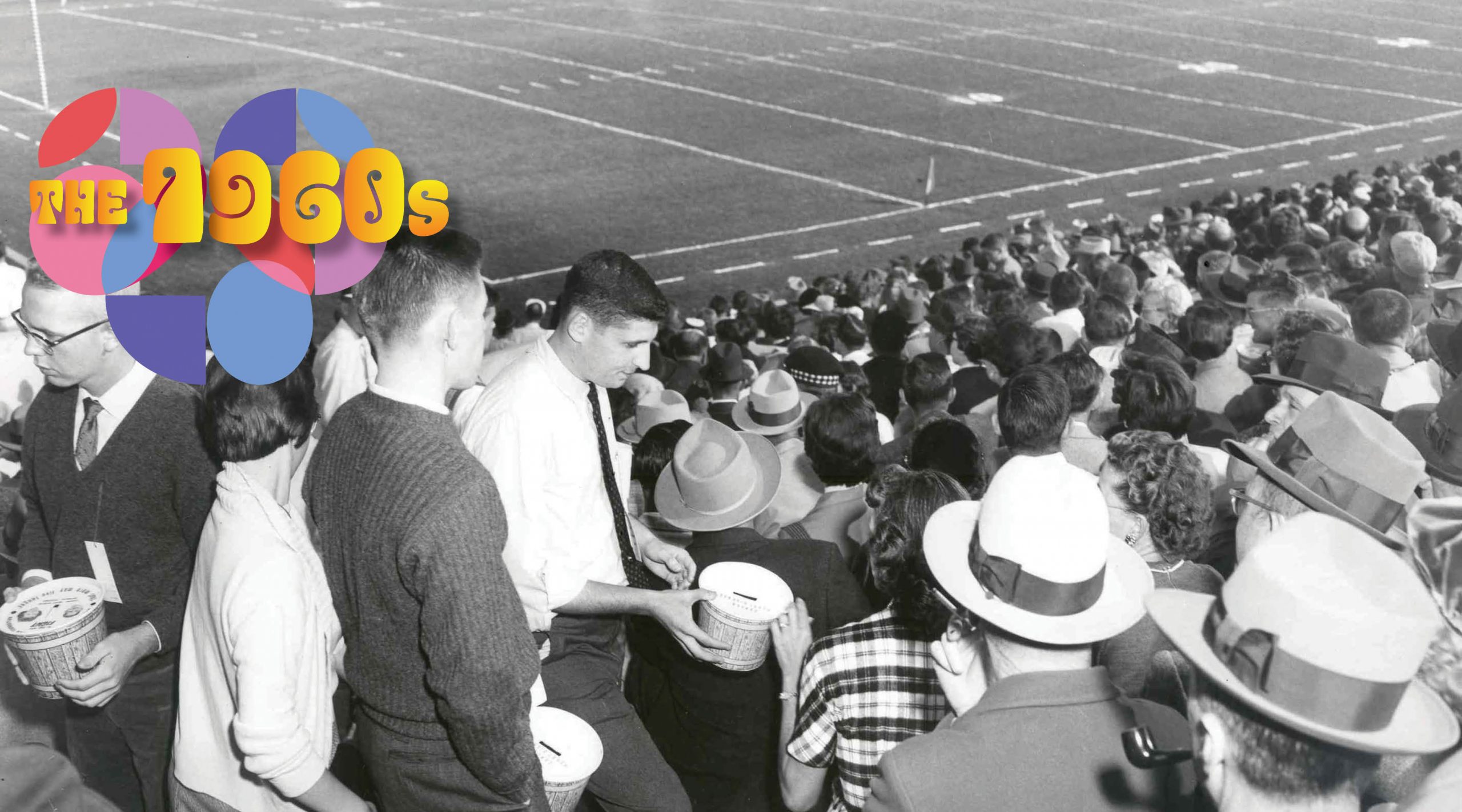

One high-profile effort was Formation Research, where volunteers and even members of the band passed buckets at football and basketball games to collect for OMRF. Along with scores of state high schools, Oklahoma’s largest universities also took part. “If the average individual contribution of those attending a game at OU, OSU and TU were only a quarter (the price of a pack of cigarettes), it would amount to $18,750 for research,” read the message on the back of a 1960 football schedule for the three universities. “Of course, contributions of any amount, $20.00 bills, $10.00 or dollar bills would be even more effective.”

These sorts of campaigns didn’t raise large amounts of money, but they did raise the foundation’s profile. So did public service announcements by celebrities, a list that ultimately included Lloyd and Beau Bridges, Larry Hagman, James Garner and Leonard Nimoy.

Over time, these efforts strengthened OMRF’s funding base. Still, the late 1960s saw a major drop-off in competitive grants, followed by the resignation of OMRF’s longtime research director. As the decade drew to a close, OMRF’s prospects mirrored those of a country mired in the Vietnam War and civil unrest: uncertain at best.

‘For the benefit of all mankind’

“In the interest of creating new medical knowledge through the efforts of the scientists of the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation for the benefit of all mankind, regardless of age, creed or color, I join with all others in the business and professional fields in lending my aid.

This grain of wheat reminds me of the endeavor of all of us who grow wheat to provide for this year’s harvest, to give as many bushels as we possibly can for the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation. When my wheat is harvested, I will deliver 200 bushels to a public grain elevator for the account of the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation.”

1961 pledge signed by Oklahoma wheat farmers

—

Read more from this issue of Findings

1940s: A Dream Becomes Reality

1950s: Opening the Doors

1960s: All Hands on Deck

1970s: Finding Firm Footing

1980s: A Time of Growth

1990s: Making A Mark

2000s: Eureka Moments

2010s: Research on the Rise

2020s: A Promising Future