Many folks of my vintage share certain opinions about today’s youth. Among those of us requiring reading glasses to make out this text, one prevalent view is that Gen Zers demand immediate gratification.

(Note from someone who had to look this up: The Pew Research Center and many others define Generation Z as those born from 1997 on.)

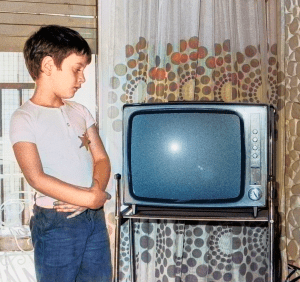

At gatherings of the no longer young, we bemoan how screens have made patience as antiquated as rotary phones. If kids today have to cool their heels any longer than the few milliseconds it takes a device to deliver exactly what they want – games, videos, all manner of digital content – they’re not interested.

Or so we grumble righteously to one another. Because, clearly, we had it much harder. I mean, we played board games for fun. We actually had to wait for our favorite show to come on at a certain time once a week. And if we missed it, we missed it.

Or so we grumble righteously to one another. Because, clearly, we had it much harder. I mean, we played board games for fun. We actually had to wait for our favorite show to come on at a certain time once a week. And if we missed it, we missed it.

When our parents didn’t show up on time to pick us up from somewhere, we just had to stand there. We couldn’t text or call them. No Instagram or YouTube to distract us. To amuse ourselves, the menu of options looked something like:

- kick an acorn

- see how long you can hold your breath

- try to remember the lyrics to Bohemian Rhapsody

- all of the above, at once

Like all curmudgeons, we believe that makes us superior to youngsters who’ve known no such deprivation. But before we spend too much time patting our own backs, we should, well, wait. Because it turns out that patience isn’t the exclusive province of those who grew up watching reruns of Gilligan’s Island.

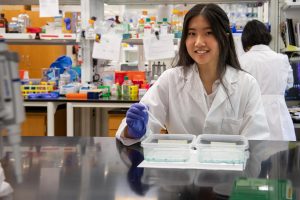

In February 2020, the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation chose 14 Oklahoma students as its 65th class of Sir Alexander Fleming Scholars. That group, all undergraduates or soon-to-graduate high school seniors, was selected from almost 100 applicants from across the state.

For nearly all of them, it would be their first chance to explore laboratory research in an in-depth way. And they’d get to do it for an entire summer.

For nearly all of them, it would be their first chance to explore laboratory research in an in-depth way. And they’d get to do it for an entire summer.

But we all know what happened next: Covid-19.

There was just no way to sequence DNA, pipette or dissect a fruit fly over Zoom. Laboratory research is, by its very nature, hands-on. So, we were forced to cancel the program.

But, we told the students, if you’re still interested, we’ll be glad to have you next summer. Assuming the pandemic cooperates.

And, for the most part, it did. When we contacted our would-be scholars in late spring, we were quite pleased when all but two of them said yes.

Those dozen students just wrapped up their summers at OMRF. And when we asked them whether it had been worth the wait, the resounding answer was yes.

For Cindy Li of Stillwater, she used the intervening year to build her scientific knowledge through coursework as a neuroscience major at the University of Pennsylvania. So, when she joined the lab of Dr. David Forsthoefel at OMRF this summer to study the regenerative properties of tiny flatworms, she was able “to pick up the technical processes and concepts more quickly,” she said. “I was able to get much more out of this experience than I would have previously.”

Edmond’s Estella Seagraves had a similar take. A cellular and molecular biology major at Oklahoma City University, she spent her summer at OMRF learning about antiviral immunity, a topic that’s particularly relevant these days.

“This program gives students the opportunity to truly learn how research works,” she said. “I know it made a significant impact on me as a person and a scientist.”

By its very nature, biomedical research is a waiting game. Experiments can take months, and sometimes years, to generate data. Even then, those results may be the opposite of what a scientist had hoped for. Which means back to the starting line for a new experiment. And more waiting.

So, perhaps, this waiting game doubled as a form of training for our would-be scientists.

Of course, we didn’t plan to keep these talented students on ice for a year-plus. But one of the unexpected silver linings of the pandemic may be the patience we’ve all had to exhibit when things don’t turn out as expected.

After all, the best things in life are worth waiting for. That, it seems, is a lesson both young and old can learn.

–

Adam Cohen is OMRF’s senior vice president & general counsel and interim president. He can be reached at contact@omrf.org. Get On Your Health delivered to your inbox each Sunday — sign up here.