Would you like a doughnut? A beer? A day off?

Perhaps you’d prefer cold, hard cash. Fifty bucks? Or maybe $100? Okay, what about $500?

These are just some of the incentives cities, states, businesses and employers are offering to encourage people to get Covid-19 vaccinations.

These are just some of the incentives cities, states, businesses and employers are offering to encourage people to get Covid-19 vaccinations.

It will not come as news that, in the U.S., the vaccination effort has rapidly transformed from an exclusive shopping event to a fire sale. As in, we just can’t give this stuff away.

Relatedly – and, again, in the not-news category – surveys indicate that a big chunk of the American public remains skeptical about the vaccine. A Kaiser Family Foundation poll found that 13% say they definitely won’t get vaccinated, 17% are taking a wait-and-see tack, and 7% will do so only if required.

It’s little wonder that The New York Times ran a story this past week in which health experts expressed skepticism that the country would ever reach herd immunity. With the steady emergence of new, more contagious variants, experts have been steadily upping their calculations as to what percentage of the population would need to be vaccinated to effectively banish the virus. Most now agree the target is at least 80%, and it will climb if more fast-spreading strains enter the mix.

“It is theoretically possible that we could get to about 90% vaccination coverage, but not super likely, I would say,” Marc Lipsitch, an epidemiologist at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, told the Times.

Against this backdrop, public health experts and private employers are increasingly asking one question: What can we do to goose vaccination numbers?

Vaccine mandates seem unlikely. There appears to be little to no energy in this direction on the governmental front, and private-sector support among employers also seems to have ebbed.

In December, at a summit hosted by the Yale School of Management, a survey of 150 CEOs of leading businesses found that 78% said vaccines should be required at work. By March, a similar poll by Willis Towers Watson found that only 23% of employers were planning or considering a vaccine requirement for employees to return to the workplace, with just 10% considering making shots a condition of employment.

In December, at a summit hosted by the Yale School of Management, a survey of 150 CEOs of leading businesses found that 78% said vaccines should be required at work. By March, a similar poll by Willis Towers Watson found that only 23% of employers were planning or considering a vaccine requirement for employees to return to the workplace, with just 10% considering making shots a condition of employment.

So, the stick is pretty much out. That leaves the carrot.

Or, more precisely, carrots. Because it seems that just about everyone is trying a different approach.

In New Jersey, proof of vaccination will get you an IPA from participating breweries. Krispy Kreme will give you – surprise! – a doughnut. West Virginia is offering savings bonds to young people who roll up their sleeves. And employers like Whirlpool ($200), the state of Maryland ($100) and Oklahoma’s very own Love’s ($75) are handing out cash to workers who do the same.

But will any of it work?

Social science evidence is notoriously difficult to rely on, especially when it attempts to predict behaviors. But in a recent study by the UCLA Health and Politics Project, about a third of unvaccinated participants said a cash payment would make them more likely to get a shot. (In the no-duh category, the percentages went up as proposed payments got bigger.)

However, this uptick was partially offset by those unvaccinated folks (15%) who said they’d actually be less likely to take a vaccine if it came with a cash incentive. And this makes perfect sense. Because someone who’s already wary about the vaccine might think, “Hey, they wouldn’t have to bribe me if this thing was safe and effective.”

In an interview with the Association of American Medical Colleges last month, Dr. David Asch, who heads the Penn Medicine Center for Health Care Innovation, expressed skepticism that any carrot would prove effective. “Financial incentives can help people who are already interested in a behavior like quitting smoking,” he said. But “what we’re really trying to do here is motivate people who don’t want to get vaccinated, … [and] I’m not sure there’s an amount of money we’d be willing to offer that would also work.”

That’s pretty much where we’ve come down at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation.

That’s pretty much where we’ve come down at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation.

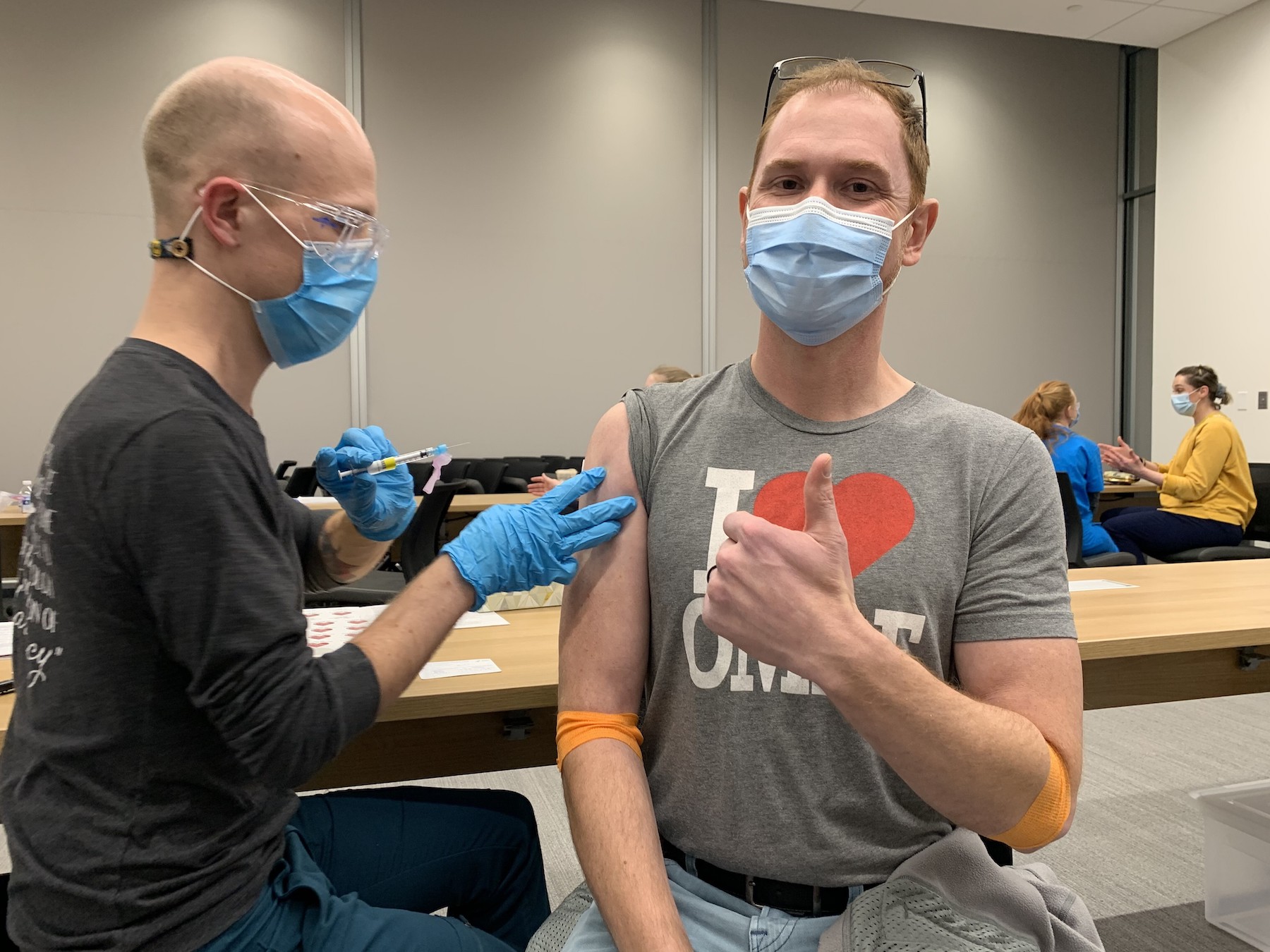

We’ve done our best to encourage our workforce to get vaccinated, and we’ve even held an onsite vaccine clinic. That’s brought our overall (self-reported) vaccination rate among our workforce to 81%.

We’ve contemplated what we can do to get that final 19% inoculated. We could dangle some sort of cash or other incentive, but as you can see from those numbers, we’d mostly end up paying folks who’d already done something voluntarily. And among the unvaccinated, a significant number likely wouldn’t budge.

Like just about everyone who cares about this issue, we’ll keep thinking about it. Maybe we’ll even try some experiments, because, hey, that’s what we do at OMRF.

In the end, though, we might well end up right where we are now. Because, to borrow from Winston Churchill, voluntary vaccination may prove the worst way to end the pandemic, except for all the other ways that have been tried.

–

Adam Cohen is OMRF’s senior vice president and general counsel. He can be reached at contact@omrf.org. Get On Your Health delivered to your inbox each Sunday — sign up here.