Multiple sclerosis threatened to rob a young opera singer of her future. An OMRF physician helped her get it back.

By Lindsay Thomas | Photography by Brett Deering

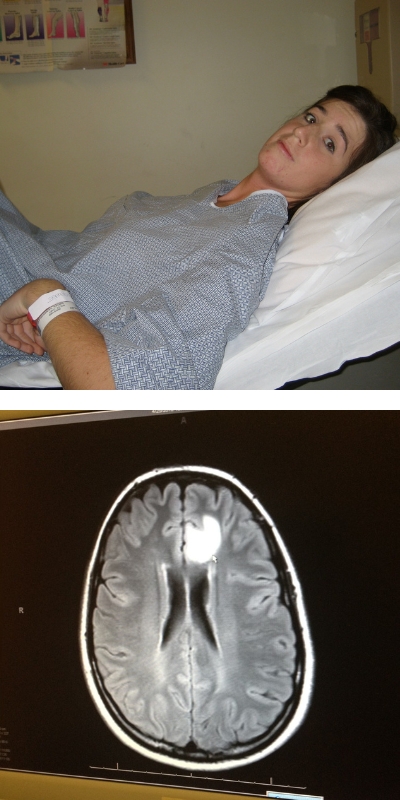

The stoplight turned yellow, then red. Or at least that’s what Kelsey Stark thought it did. As she sat behind the wheel of her car, she realized she could barely see the traffic signal.

Then 23, Kelsey had first noted problems in her vision months before. She’d gotten glasses, but when her eyesight continued to worsen, she’d returned for a new prescription and, again, for contacts. The aspiring opera singer chalked the eye issues up to long hours of studying and rehearsals to earn her master’s degree in vocal performance.

After the sight in her right eye further deteriorated, she’d concocted another simple explanation: a scratched cornea. Once her finals and auditions for summer internships were wrapped up, she’d resolved to make an appointment to see a local ophthalmologist.

But now, at the New Jersey intersection, the center of her vision had gone completely black. Around the edges, everything appeared shattered, almost like someone had dropped a brick on her windshield.

Later, Kelsey would scroll back in her mind to this instant and understand. But in the moment, she just cocked her head and looked to the sky. When she spied a shard of green at the edge of the darkness, she drove on.

•••

Kelsey went back to the optometrist who prescribed her contacts. A staff member examined her and immediately phoned the on-call ophthalmologist, who referred her to an eye hospital in Philadelphia.

She enlisted a friend to take her. In the exam room, a nurse flipped on the eye chart on the opposite wall. An oversized, black capital “E” glowed back at them. “What do you see?” the nurse asked. Kelsey blinked. “I said, ‘I can’t see anything,’” Kelsey remembers. “My friend nearly fell out of his chair.”

A physician diagnosed the young soprano with optic neuritis, which occurs when inflammation damages the brain’s optic nerve. She was admitted, and her symptoms rapidly worsened: her knees became numb, her face started to tingle, and she lost all sensation of temperature from the waist down. After two nights in the hospital and a battery of tests, her medical team told her she might have multiple sclerosis, or MS.

Kelsey had never heard of MS. “I was young. I thought I was indestructible, and a good night of sleep was all I needed,” Kelsey says. She just wanted to wake up from this bad dream. “I didn’t have time for a disease in the middle of my pursuit to become a classical singer.”

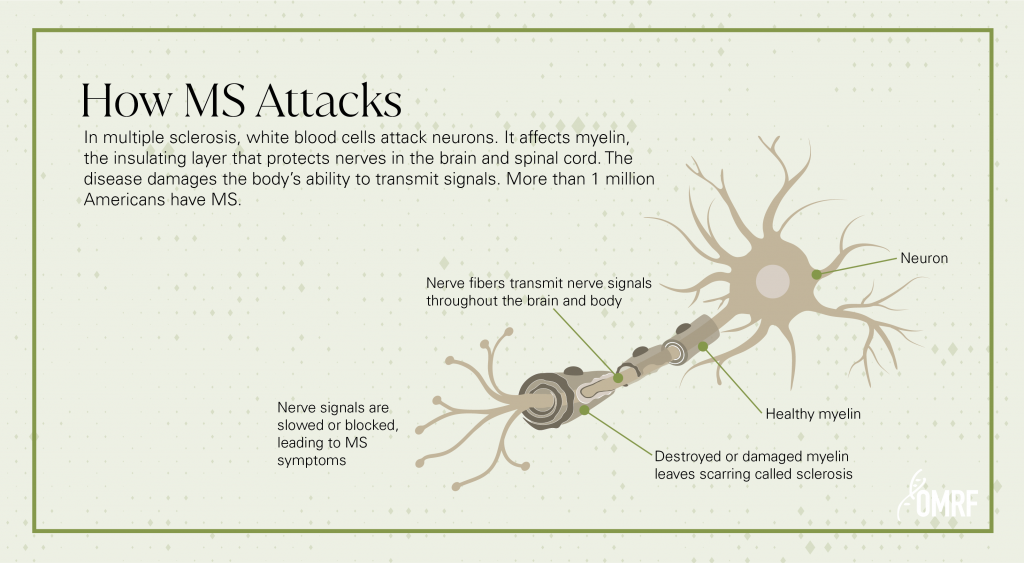

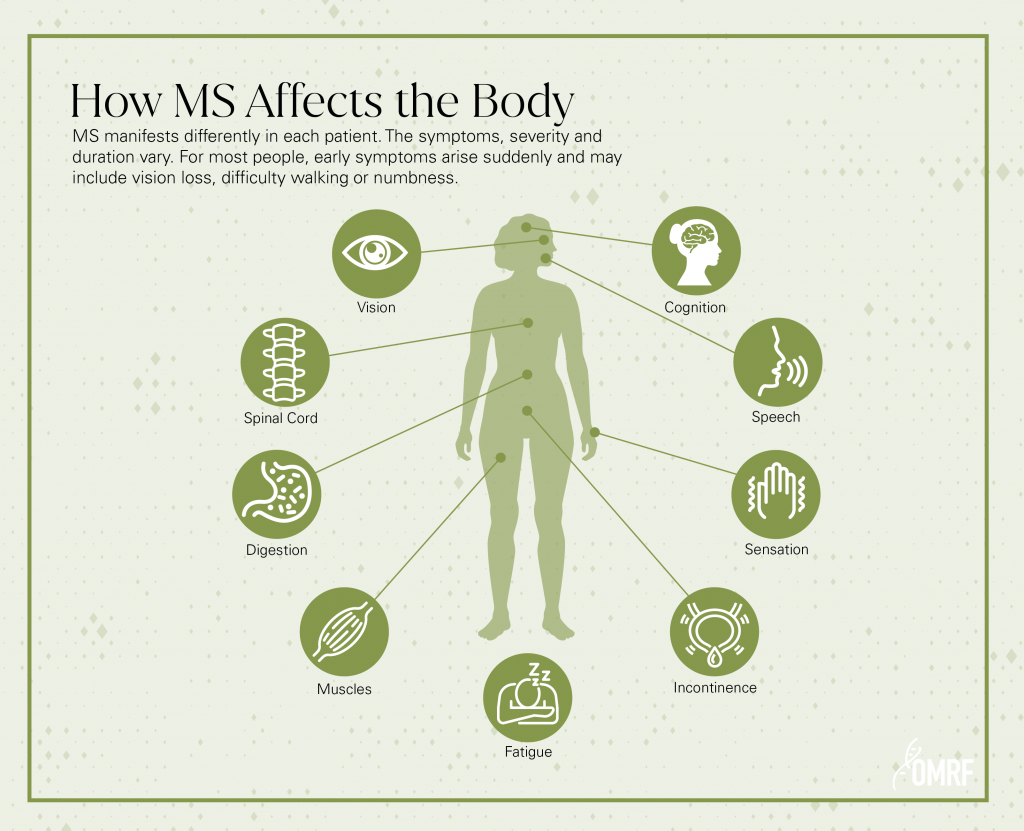

In MS, the immune system attacks the body’s myelin, the insulating layer that protects nerves in the brain and spinal cord. The disease damages the nervous system’s ability to transmit signals throughout the body. Although the condition manifests differently in each person, symptoms often include vision impairment. But the disease can also bring problems with balance and coordination, incontinence, muscle weakness and control, fatigue, numbness, and difficulty with speech, memory and concentration.

Research has found that for nearly 20% of patients with MS, optic neuritis is the first symptom of the disease. The condition occurs when the optic nerve’s protective layer is stripped away, resulting in temporary blindness.

At some point, researchers estimate, more than half of all people with MS will experience the phenomenon. Disease flares can exacerbate vision loss, but with treatment, sight usually comes back. In some cases, though, the damage can become permanent.

In the hospital, Kelsey underwent an MRI. The images showed a tumor-like lesion in her brain nearly the diameter of a golf ball.

Within days, physicians delivered a definitive diagnosis. She had MS.

As with most patients, Kelsey’s MS began in a relapsing-remitting form. However, she had “active” relapsing-remitting MS, which meant frequent disease flares. Despite daily injections and intravenous steroids, every subsequent MRI showed more damage. Over time, the illness progressed, resulting in growing levels of disability.

Kelsey lost feeling from the waist down. She had debilitating headaches. Optic neuritis returned – in both eyes – twice. She felt tired all the time, and walking became challenging. Her medications even changed her voice, taking her ability to hit high notes with the clarity she had cultivated for a decade.

Her boyfriend, Gerard D’Emilio, was training for his own operatic career at the same school. He could see the daily toll that MS – and its treatments – took on her. “She had all the side effects of the medications with none of the benefits,” he says. “The disease just got worse.”

Kelsey returned to school and worked hard to hide her disease. She bought stiff shoes to disguise her difficulty walking and refused the cane that helped stabilize her. In a seminar one afternoon, her left leg went numb. Class adjourned, and she couldn’t get out of her chair.

“I realized that this disease was stronger than I was,” she says.

Still, Kelsey was determined. She was cast as the lead in an opera. But to accommodate her deteriorating mobility, the director had to arrange the set so that she could use furniture as stabilizers or seats to disguise her struggles. “My disease was so unpredictable, we had to change course daily. After wrapping the show, I realized I couldn’t hide it anymore,” she says.

“That was her lowest point,” says Gerard.

The pair married and moved to Minnesota, where they joined an opera company. Kelsey’s medications were so ineffective that she wondered if doctors had misdiagnosed her. Even a phone call could exhaust her.

If her body lacked the stamina to deal with everyday life, she knew it couldn’t meet the demands of an operatic career. Even more devastating, she believed she and Gerard would never become parents; unable to care for herself, she certainly wouldn’t be able to care for another human being.

After three years of taking medications that didn’t help her, Kelsey decided she was done with MS treatment.

Seeing the state of his wife’s mental and physical health, Gerard believed she needed a familiar landscape. He convinced her to return to Oklahoma, where she’d grown up, and where her parents still lived. And where, soon, she’d meet Dr. Gabriel Pardo.

•••

•••

Before starting medical school, Pardo thought he’d become a pediatrician. But by his residency, he’d found a deeper calling: neuro-ophthalmology.

The field focuses on the relationship between the eyes and the brain. Pardo was fascinated by how the pair worked together to create vision, and he went on to complete a fellowship in the subspecialty. While there, he began to encounter patients with multiple sclerosis.

The disease takes a toll on every part of the body. It has no cure, and its damage builds over time. Because symptoms are different in everyone, it can go undiagnosed for years.

“One patient could come to you with double vision, and another could have issues with bladder control. That’s it. And they both have MS. No single symptom is present in every patient,” says Pardo.

Pardo joined OMRF in 2011 as the founding director of OMRF’s Multiple Sclerosis Center of Excellence. Envisioned as a one-stop shop for people with MS, the center would become the only comprehensive MS center in the region, providing neurology, ophthalmology, physical therapy, general wellness education, an onsite laboratory for patient samples, plus an infusion suite and access to clinical trials.

Kelsey wasn’t eager to begin treatment again. But her mother, Mary Stark, knew OMRF’s reputation for MS care, and she convinced her daughter to see Pardo in 2016.

In their first visit, Pardo assessed Kelsey’s situation. Her MS was not well controlled, and standard therapies had proven ineffective. He recommended she enroll in a clinical trial of ocrelizumab, a medication that wasn’t yet commercially available. The drug attacked the disease in a novel way, going after a particular immune cell that incites inflammation in the body.

Even though she’d just met him, Kelsey felt seen and heard by a physician in a way she hadn’t experienced. “He was the first doctor who explained the science behind the medication,” says Kelsey. Pardo gave her an overview of the research scientists were doing at OMRF. She sensed he didn’t want to merely manage her disease. “He was looking for a cure,” says Kelsey. “I felt the entire MS Center of Excellence was part of my team to overcome this disease.”

She and her family also saw that OMRF offered a patient-centered environment. “Trying to treat my MS used to be a full-time job,” says Kelsey. “But once I came to OMRF, what used to take six months took one day.” Instead of the patchwork of different sites for labs, infusions and appointments with specialists she was accustomed to, everything happened in the same facility. The staff knew her name. Even the parking was convenient.

“As soon as she walked in those doors, everyone cared about her,” says Mary.

Kelsey opted into the trial. Six months after her first dose, an MRI found her brain and spinal lesions were nearly gone.

Soon, feeling returned in her body where it was lost. Her headaches calmed, vision improved. Walking was no longer a chore. Energy returned. And unlike other drugs, it didn’t affect her singing voice. “I got my life back,” says Kelsey.

She hasn’t had a relapse since starting the drug, which she continues to receive by infusion every six months at OMRF.

The Food and Drug Administration approved the medication in 2017. Today, Pardo says, it’s the most-prescribed MS drug in the world.

•••

•••

Once Kelsey was on an effective medication, she was able to return to music. She earned her doctorate in vocal performance from the University of Oklahoma and joined the faculty at Shawnee’s Oklahoma Baptist University, where she rose to chair its music division. Earlier this year, she and Gerard welcomed Luca, the son they thought they would never have.

Just before their first grandchild was born, Kelsey’s parents, Jack and Mary Stark, met with Pardo to express their gratitude. They also told him they wanted to find a way to help more families have this same experience.

To receive a $1.5 million challenge grant from the Stark Family Foundation, OMRF must raise a matching $1.5 million. “OMRF gave Kelsey her life back,” says Mary Stark. “Jack and I want everyone facing MS to have access to the same life-saving care and treatment our daughter found at OMRF.”

Funds will be used to recruit a new physician-scientist to the MS Center, expand psychosocial care for its more than 3,000 patients, and grow the center’s technological infrastructure.

You can join the challenge today at

omrf.org/MSAdvocate.

In February, the Stark Family Foundation announced a $1.5 million challenge grant to OMRF. The gift, which requires OMRF to raise a matching $1.5 million, will be used to increase the center’s patient and research capacity by adding a new physician-scientist and a social worker, purchasing an MRI machine, and expanding the foundation’s biorepository to store more patient samples for research.

“These funds will allow Dr. Pardo to expand his resources to meet the needs of his growing patient base,” says Jack.

One person who’s particularly excited about the growth is OMRF’s Dr. Bob Axtell, who studies MS. “Having more people looking at a problem is always a good thing,” he says.

Axtell’s team is working to find new targets for MS medications and develop prognostics to improve clinical care. His lab recently identified new blood biomarkers for the disease, which could help detect a relapse sooner or perhaps even prevent it. That work, he says, is fueled by patients like Kelsey, who not only visit OMRF for care but also to participate in research studies that help deepen scientists’ understanding of MS.

He walks into work every day alongside the people he’s trying to help. “Seeing each patient and knowing that they may be gracious enough to donate samples for our work is very meaningful,” says Axtell. “I also see their challenges. Understanding that we could impact them and people who haven’t even been diagnosed yet is a day-to-day reminder of what we’re trying to do.”

Since Axtell joined OMRF a decade ago, the FDA has approved a dozen new therapies for MS. The advances are thanks in no small part to patients like Kelsey, who participate in clinical trials of investigational drugs. And though her experience with ocrelizumab has transformed her life, her challenges haven’t disappeared.

Her medication suppresses her immune system and makes her more susceptible to infection. She’s extremely sensitive to heat. Her mobility challenges are a fraction of what they once were, but they aren’t gone.

Still, Kelsey says it’s the closest thing to a cure she’s ever felt. “Miracles can come in the form of scientific advancements,” she says. “I think that’s what I experienced.”

She knows that with MS, questions continue to outnumber solutions. But she’s confident the place that helped get her life back on track can do the same for others. “OMRF was an answer to our prayers. It’s where hope begins.”

Give Today: Join the MS Advocate Challenge

—

Read more from the Summer/Fall 2023 issue of Findings

Oklahoma’s Treasure

Voices: Jim and Norma Freeman

Ask Dr. James: Preventing Alzheimer’s Disease

Matters of the Heart

Unfinished Business

The Aerialist

77 for 77

End of an Era