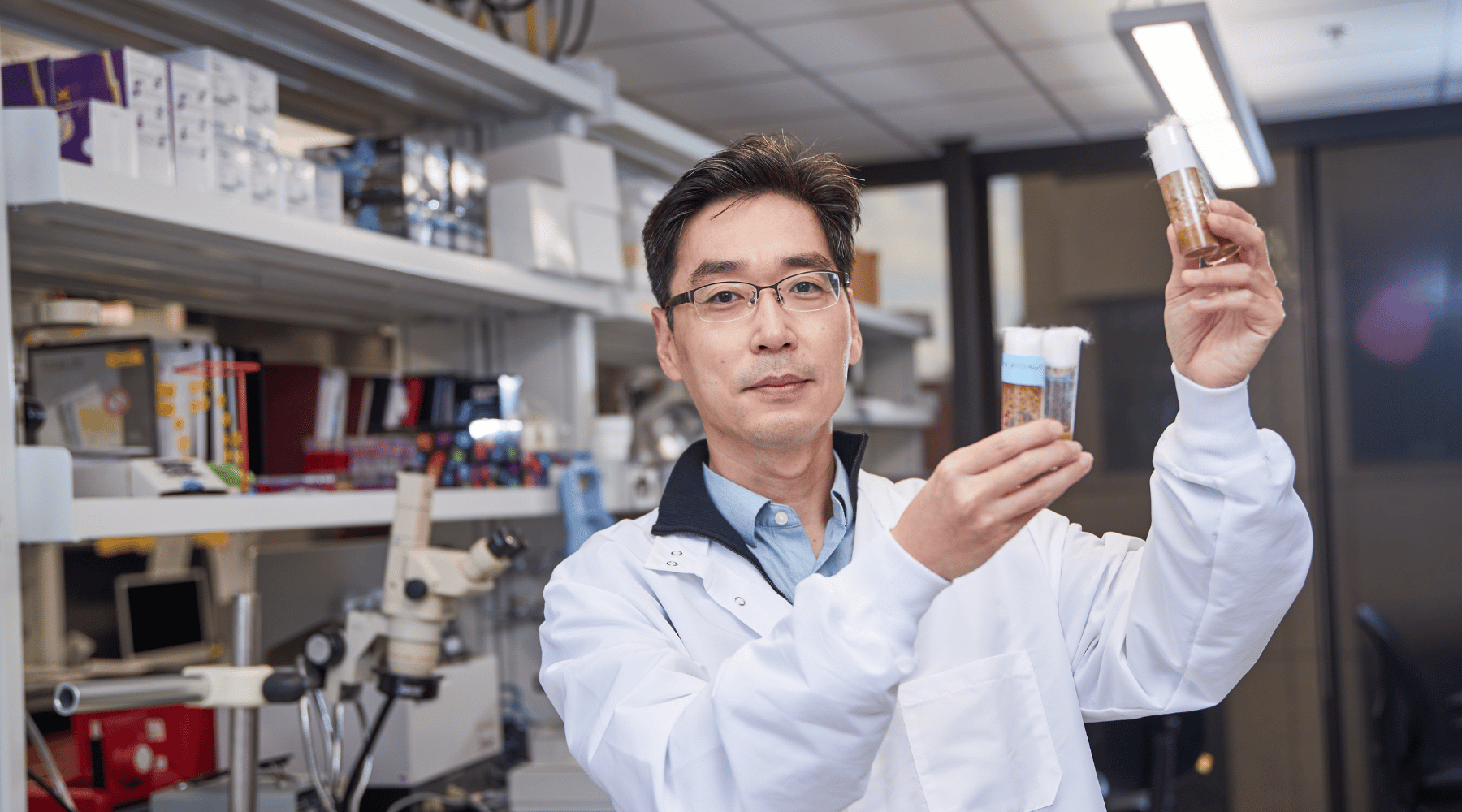

Wan Hee Yoon, Ph.D., has proven so adept at unraveling rare neurological diseases that two of them bear his name.

The Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation scientist now hopes his newest grant will help him identify a potential treatment for one of those genetic conditions.

With a four-year, $150,000 grant from the Israel-based Binational Science Foundation, Yoon will focus on a genetic variant that causes Harel-Yoon Syndrome, a condition he co-discovered in 2016.

The disease is characterized by a wide range of symptoms, which include intellectual disability and muscle weakness and spasticity. In the most severe cases, life-threatening complications such as respiratory failure begin immediately after birth. Milder forms cause developmental delay, brain malformations, and eye and heart abnormalities.

“As recently as three years ago, there were only a few dozen confirmed cases,” Yoon said. “We now think there are more than 100, and the number will continue to grow through continued research and genetic testing.”

Yoon normally pinpoints rare neurological conditions using the common fruit fly, or drosophila, as his research model. About 75% of the fruit fly’s genes mirror those in humans.

In this case, Yoon will focus on a gene known as ATAD3A. That gene plays an important role in the mitochondria, often called the powerhouse of the cell. In people born with a broken copy of ATAD3A, the mitochondria can’t produce energy properly.

Yoon will test a form of gene therapy – the use of a molecule that he hopes will either silence or fix the defective copies of ATAD3A without harming the healthy versions.

“A genetic variant is a like a typo in an instruction manual, but in a human being a typo can have awful consequences,” Yoon said. “Our proposed remedy would serve as an eraser for that typo.”

Yoon will try the experimental treatment on the cells of human patients of Harel-Yoon disease, using a technology that converts skin cells into neurons. Additionally, scientists in Israel will test this theory on a paperclip-sized species called zebrafish.

“If these experiments succeed,” said Benjamin Miller, Ph.D., who heads OMRF’s Aging & Metabolism Research Program, “we hope to be one step closer for families affected by this disease in the future.”