Saturday will mark a half-century since Neil Armstrong became the first human to walk on the moon. In the 50 years since, space missions have had an unlikely touchpoint right here in Oklahoma—at OMRF.

In 1978, Shannon Lucid, Ph.D., then working as a post-doctoral researcher at OMRF, was selected as part of the first class of female astronauts in NASA’s space shuttle program. Her time at OMRF, where she’d studied how chemicals cause cancerous changes in cells, had not prepared her for the media onslaught that followed the announcement.

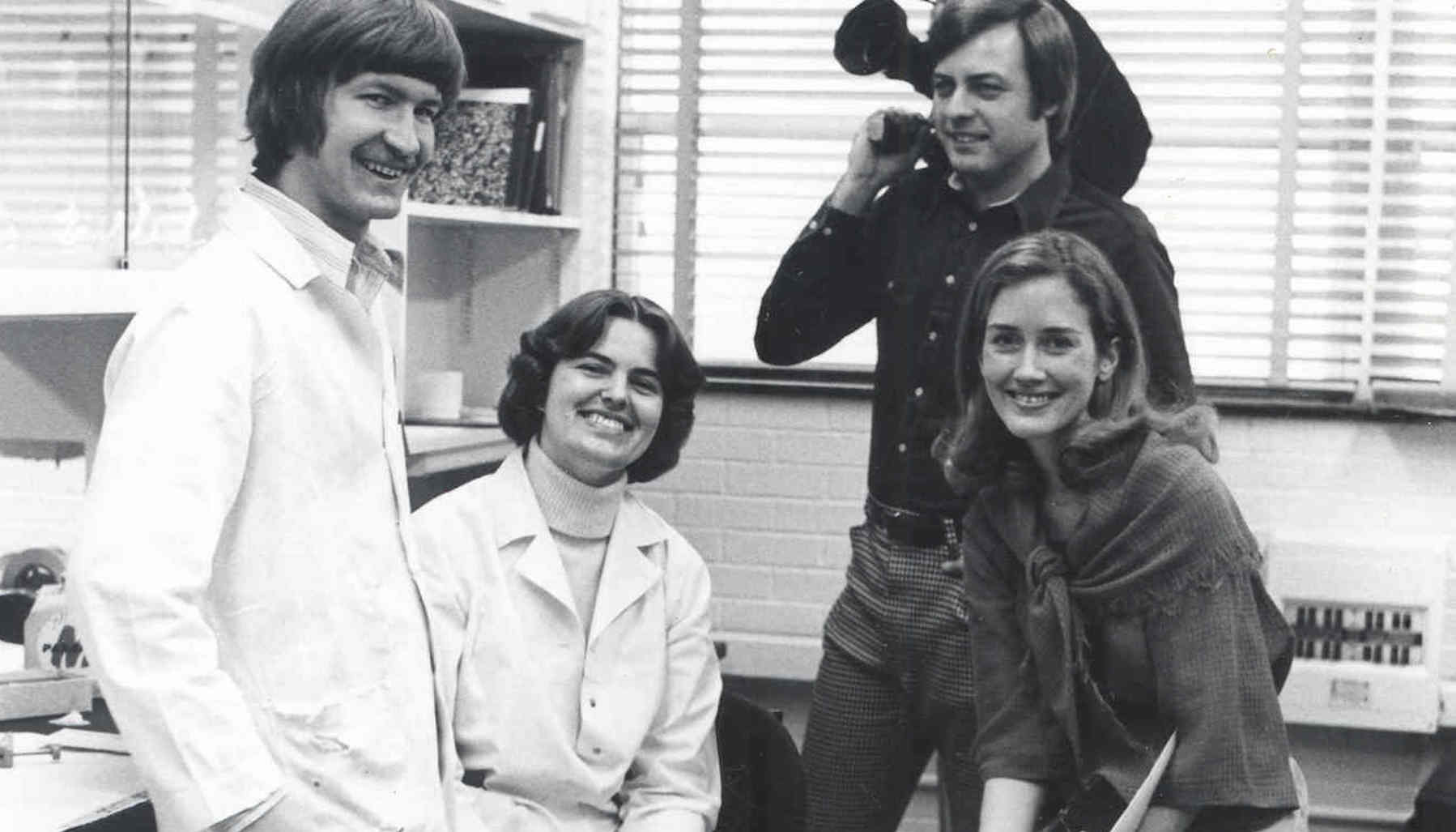

Local and international news outlets, including crews from Time, Life and People magazines, came to OMRF to interview Lucid. She even appeared on the CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite.

Despite Lucid’s newfound fame, she remained “very down to earth,” said Don Gibson, who worked in the lab with Lucid during the six-plus years she was at OMRF. She spent several months wrapping up her scientific projects at the foundation, determined not to leave any loose ends for her colleagues.

It took seven years of training, but in 1985, Lucid became the sixth American woman to reach space. And as a mission specialist aboard three different space shuttles, she put her scientific training to use.

She conducted a project on the growth of ice crystals and studied the effects of space on wild wheat. She observed quail embryos and, in a nod to her days at OMRF, even did a project with lab rats.

“On the Columbia, we had 48 rats to tend, and I worked with them every day,” Lucid told OMRF’s Findings magazine in 2016. “No one else on the mission had ever done that sort of thing, so I was a natural for that task.”

While NASA’s research has focused on what transpires far above the earth’s surface, many of the projects on space flights also aim to change things right here on our planet. That was the case with a pair of experiments that OMRF’s Allen Edmundson, Ph.D., sent into space in 2003 aboard the shuttle Columbia.

The experiments involved taking cells from cancer patients in their natural, liquid form and transforming them into solid crystals. Once the cells had been crystallized, which happens more readily in the gravity-free atmosphere of space than under earthbound conditions, Edmundson planned to bombard them with radiation to study their structure. He hoped that unmasking the cells’ structure might lead to new cancer treatments.

However, after 16 days in space, the Columbia disintegrated upon re-entry to the earth’s atmosphere. All seven astronauts on the shuttle died.

When Edmundson later viewed photos of shuttle debris found near Nacogdoches, Texas, he was stunned. There, amidst the wreckage, was a small, aluminum container that had held his experiments.

“I couldn’t believe that our little box could have survived a fall from 200,000 feet,” he said. Still, his experiments did not.

The Columbia tragedy put a temporary halt to human space flight, but those missions eventually resumed. This past March, Vice President Mike Pence announced that NASA was aiming for a new generation of Americans to reprise Armstrong’s lunar landing by 2024.

“We still have so much to learn from space,” said OMRF President Stephen Prescott, M.D. “Judging from history, I feel confident that Oklahoma scientists will continue to contribute to this process of exploration and discovery.”