For Dr. Jake Kirkland, research has always been a “go where the science takes you” proposition. As a postdoctoral fellow at Stanford University, he was part of a team that identified genes that seem to predict which patients’ tumors will respond to a particular chemotherapy drug.

That drug, doxorubicin, is known as the “red devil” because of its Kool-Aid-like color and punishing side effects.

When it came time to open his own lab, Kirkland decided to follow that work. Specifically, he set a goal of better identifying those whose tumors won’t respond to the therapy. That way, he might be able to help spare patients from a futile course of treatment that can lead to collateral damage ranging from heart and brain damage to infertility. “If success is highly unlikely,” says Kirkland, “a patient shouldn’t have to go through all that.”

A lifelong Californian, Kirkland zeroed in on OMRF because of the “rigorous scientists” in the foundation’s Cell Cycle & Cancer Biology Research Program. And when that group of scientists met Kirkland, the attraction proved to be mutual.

“His enthusiasm was obvious,” says Dr. Susannah Rankin, who led the hiring process at OMRF. “He’s working on important projects, tackling things that are closer to the clinic than what the rest of us in the program do.” She and her colleagues saw an opportunity to lift all boats: “He’s going to make us better, and we’ll make him better.”

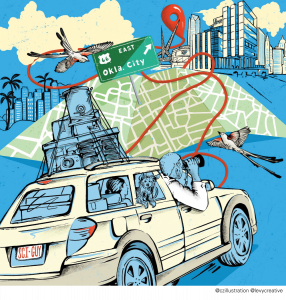

When Kirkland and his wife, Brionna Seley, arrived this past spring in Oklahoma City, its energy struck them. “Lots of cities claim to be on the rise, but you can really feel it here,” he says.

The couple thought their new home would be just for the two of them, plus their 10-year-old rescue mutt, Zoe. But when they found a stray, visually impaired Australian Shepherd dodging cars in the city’s Plaza District, Cherry (named for her pink nose) joined the family.

Cherry represents but the latest addition to a life that’s already full to the brim. Outside the lab, Kirkland is an avid birder and wildlife photographer, a woodworker, a chef, and an amateur herpetologist. His home brewery also awaits reassembly in his garage following the trip from Silicon Valley.

His hobbies, he says, “involve lots of quiet time,” which clears Kirkland’s head to devise new hypotheses and experiments. “Some people think best in the shower. I do my best thinking out in the field with my camera and binoculars.”

These days, much of that thought revolves around why doxorubicin works so unpredictably. “In breast cancer, the success rate for this chemotherapy is around 50%. We want to raise that number,” he says.

He also aims to understand what’s causing some people’s bodies to resist treatment – and whether scientists can change that. “If we can do that,” Kirkland says, “the drug could help them.” For those patients, breakthroughs from Oklahoma’s newest cancer researcher can’t come soon enough.

—

Read more from the 2022 Winter/Spring issue of Findings

Family Matters

Lessons in Philanthropy

Hitting the Target

Life Changer

How Yellowstone’s hot springs paved the way for DNA testing

Voices: Nancy Yoch

Strange Things