After 36 years at OMRF, Dr. Rod McEver hangs up his lab coat

In retrospect, the path of life can seem clear, even foreordained. Yet as we live it, daily existence often feels like a random smattering of minor events and decisions. Most add up to little in the grander scheme, mere raindrops in the river. But every so often, a gush makes the water swell beyond the banks, pushing the stream in a direction it might not otherwise have flowed.

Dr. Rod McEver had just this sort of moment during his third year of medical school at the University of Chicago. Actually, he had two.

During his rotation in the hematology ward, he treated an elderly patient for a blood disorder. Her husband visited frequently, and the pair grew fond of the slender doctor-to-be with a soft drawl forged during formative years split between Louisiana and Oklahoma. The patient’s condition improved, and when she was discharged, the couple, both Jewish, told McEver they would donate money to plant a tree in his honor in Israel.

During his rotation in the hematology ward, he treated an elderly patient for a blood disorder. Her husband visited frequently, and the pair grew fond of the slender doctor-to-be with a soft drawl forged during formative years split between Louisiana and Oklahoma. The patient’s condition improved, and when she was discharged, the couple, both Jewish, told McEver they would donate money to plant a tree in his honor in Israel.

While on that same rotation, McEver also took care of a 20-year-old poet with leukemia. When McEver explained to him that the chemotherapy drug used to treat his blood cancer derived from a purple, flowering plant, he composed “Ode to the Periwinkle Plant,” a meditation about how a thing of such beauty could also treat a deadly disease. He gave McEver a book of his work when he left the hospital. However, the patient’s leukemia proved intractable, and he died a year later.

When it came time to select a specialty, McEver remembered those patients. He chose hematology, which focuses on the physiology of the blood. He did so knowing that the path ahead would often be difficult. Indeed, treatment had failed the young poet he’d befriended. But the human bonds he’d forged – and the challenging medical problems that the blood presented – called to him.

McEver completed his medical school residency and hematology fellowship in the ensuing decade. He launched a career as a physician-researcher and soon pinpointed a protein in the blood that no one had identified before. The body rapidly mobilized that protein, which came to be known as P-selectin, to sites of injury and infection. “We knew we had discovered something very important in immune challenges and bleeding,” says McEver. “It was quite exciting.”

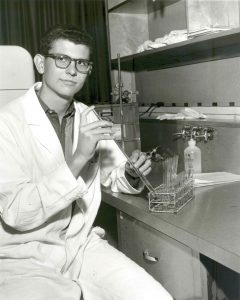

Around that time, McEver decided to join OMRF. As a teen, he’d gotten his first taste of medical research at the foundation as a Sir Alexander Fleming Scholar. When he returned, he hit the ground running. Within three years, his team had found P-selectin’s function: mobilizing white blood cells to hunt down and stop invaders such as bacteria in the body.

Over the next 30 years, he studied the protein from just about every imaginable scientific angle. His hope was always to find a bridge between insights in the lab and ways to improve treatments for patients. But, he says, that connection could never be forced. “You stay committed to fundamental science. You pursue interesting questions with tenacity, no matter where they take you.”

For McEver, that pursuit eventually brought him to sickle cell disease. An antibody he developed to block the effects of P-selectin showed promise as a therapy for the genetic illness, a debilitating and sometimes fatal blood disorder that affects an estimated 100,000 Americans. In 2019, Adakveo, a drug based on McEver’s work, became the first FDA-approved treatment for the pain crises that accompany sickle cell disease.

McEver considers the drug “a cherry on top” of his life’s work. “It’s the dream of every physician, and certainly every scientist,” he says, “to do something that can make a difference with patients.”

To Dr. Lijun Xia, who came to OMRF to train with McEver and ultimately succeeded him as chair of the foundation’s Cardiovascular Biology Research Program, the arc of his mentor’s professional life “connects all the dots” – from physician not satisfied with available therapies to scientist who developed a drug. “That’s a perfect career.”

In his final years at OMRF, McEver applied many of the lessons he’d learned in the lab in a new role: vice president of research. When he agreed to take on the role of the foundation’s chief scientific officer, “I knew we were in good hands,” says Dr. Courtney Griffin. “I knew he would keep the best interests of OMRF’s scientists front and center.”

Under McEver’s watch, National Institutes of Health funding at OMRF grew substantially, led by a major new Centers of Biomedical Research Excellence grant. Despite a plan to retire in 2021, he stayed on for an additional two years to help lead the foundation through the presidential transition that followed the death of Dr. Stephen Prescott.

When Dr. Andrew Weyrich had a full year under his belt as OMRF’s 11th president, McEver finally retired in March, on his 75th birthday. Before he did, though, he spent months working with Griffin, his successor. She was struck, in particular, by one Saturday in which he devoted 2½ hours to guiding her through “every inch” of the foundation. Though Griffin had joined OMRF 15 years earlier, McEver wanted to ensure she understood every nook and cranny of scientific space for which she’d be responsible. That attention to detail, Griffin says, “gave me the confidence I needed.”

The foundation’s Board of Directors named McEver a Distinguished Career Scientist, one of only nine in OMRF’s history. That means he will maintain an office and occasionally come by the foundation to lend, on request, a bit of his wisdom. But, he says, not too much. “I’m not going to try to micromanage.”

With his wife, Gigi, he has leaned into a pair of hobbies: exercising and reading. They’ve also embarked on an ambitious travel schedule, with trips this year already to New Orleans, Australia, Iceland and Greenland. Next up are visits to Switzerland and the Galapagos Islands.

When he’s home, McEver still looks at that book of poetry every once in a while. And he likes to imagine that somewhere in Israel, a tree planted in his honor grows tall and strong.

Illustration: @zehotavio @levycreative

—

Read more from the Summer/Fall 2023 issue of Findings

Oklahoma’s Treasure

Voices: Jim and Norma Freeman

Ask Dr. James: Preventing Alzheimer’s Disease

Matters of the Heart

Unfinished Business

The Aerialist

77 for 77

A New Beginning