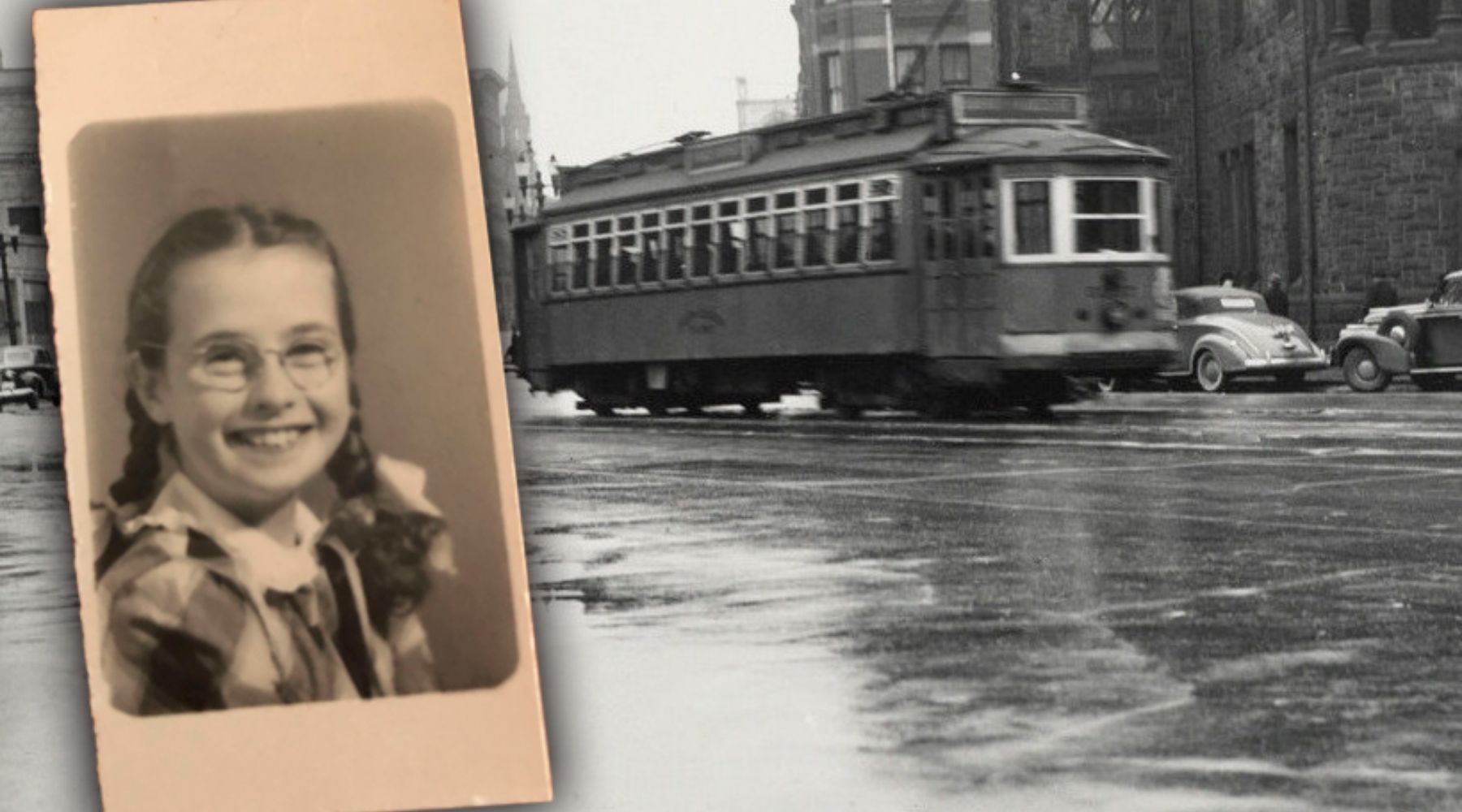

I’d like you to meet my mom.

I’d like you to meet my mom.

Regina Buckley was born in South Boston during the Great Depression. Her mother died when she was 6, and Mom remembers eating freshly baked jelly doughnuts she’d purchase each morning before climbing onto the streetcar to attend girls’ Latin school.

A strong student, she skipped a grade and earned a chance to attend the University of Chicago on a full scholarship following her junior year of high school. But her father worried about sending his 16-year-old daughter to the Windy City, so, instead, she headed to Goucher College, an all-women’s institution in Baltimore. She earned her degree and entered graduate school in math.

She met my dad while working a summer job. They married, and when he landed a faculty position at the University of Pennsylvania, she moved her graduate studies to UPenn. But she stopped short of her Ph.D. when her advisor left for another institution.

Like many women at that time, she then put her career on the backburner to have kids. She threw herself headlong into parenting my brother, sister and me, packing our lunches every day in neatly lettered brown bags, ferrying us to and from after-school activities in the family’s mustard-yellow Plymouth, then helping us with assignments once she’d cleaned up the dinners she’d cooked for us.

Math, of course, was her specialty. But her real superpower was keeping an even keel.

One day, when I was on the verge of melting down over a particularly challenging math problem, she handed me a tennis ball. On it, she’d written the word “fit.”

I gave her a puzzled look. “This way, you can do your homework and throw a fit,” she said. I giggled, forgetting my frustration. Crisis averted.

When we kids were old enough, Mom found her way back into the workforce teaching math, first in high school, then as an adjunct instructor at Villanova University. In her late 50s, after surviving breast cancer, she earned the doctorate that many years earlier had eluded her. And those twin watersheds, along with the fact that my siblings and I had emptied the nest, seemed to set her free.

She left my father and took a tenure-track faculty position at Villanova. Outside the classroom, she was like the Energizer Bunny, traveling whenever she could, skiing, biking, going to the gym, dating. She ran a half-marathon, training in her careful, mathematical way by running laps around a track until she’d built up to 53 (!), the number required to exceed 13.1 miles.

She ostensibly retired from Villanova when she turned 65, but it was retirement in name only. After six months, the department chair asked if she’d be willing to take on a semester’s worth of classes. She’d missed the students, the intellectual stimulation, so she agreed – and that semester eventually stretched into another 17-plus years at the blackboard.

In between, she crisscrossed the country, splitting time between New Mexico, where my brother lives, and Oklahoma, where she doted over my kids. Even with her retirement (for real this time) from Villanova the month she turned 83, it seemed like she might continue to confound Father Time.

But, of course, that guy is undefeated.

The last two-and-a-half years have taken quite a toll on Mom. Circulatory problems have dogged her, leading to a loss of mobility and balance, as well as repeated falls and fractures. Now in a wheelchair, her dream of one more trip to Europe seems just that.

We discovered, too late, that she’d failed to pay her taxes during the pandemic. Her conversations more and more have taken on the flavor of monologues, often looping back decades and revisiting well-traveled ground. I mentioned this to my neighbor, a physician who primarily treats the elderly, and he suggested she could be grappling with early signs of dementia. “It’s toughest to diagnose in patients like her,” he said. “They have so much excess capacity that it can stay hidden for a long time.”

Over Thanksgiving, my kids and I visited Mom, who now lives in a carriage house behind my sister’s home, renovated to suit my mother’s needs. Caretakers come each day to help her.

On the final night of the visit, Mom couldn’t grasp the idea that we were having dinner, not breakfast, thinking it was morning rather than evening. A few days later, testing revealed borderline memory loss.

When I learn about new approaches to understanding and treating dementia, like the studies Dr. Mike Beckstead is conducting at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation to understand the role of the brain chemical dopamine in Alzheimer’s, I feel hopeful. Still, I know that any novel insights or breakthroughs will likely prove too late to help Mom.

As we flew home, my son Will said he felt saddened that my nieces – aged 6, 6 and 8 – would not know the same Grandma he had. The one who’d been a fixture at his youth baseball games, played Scrabble with him, hiked alongside him up one of New Hampshire’s tallest mountains.

Although Will is right, I’m trying to think about the situation differently. I want to cherish the time Mom and I have had together. And to make the most of what remains.

—

Adam Cohen is OMRF’s senior vice president & general counsel and interim president. He can be reached at contact@omrf.org. Get On Your Health delivered to your inbox each Sunday — sign up here.