Every few months, my friend Robert and I try to get together for lunch. Robert is not his real name, but we really have been grabbing burgers (his: ham; mine: veggie) and onion rings for probably 20 years.

Every few months, my friend Robert and I try to get together for lunch. Robert is not his real name, but we really have been grabbing burgers (his: ham; mine: veggie) and onion rings for probably 20 years.

Last week, I bought, as Robert had just celebrated a birthday. This one, he said, had proven particularly tough.

Not the day itself, which he’d enjoyed by having dinner with his parents. “For some reason, I just took the opportunity to tell them each the things that I loved and appreciated about them,” he said.

The next morning, his mother called. “Your father wants to talk to us both,” she said. He showered and hurried over.

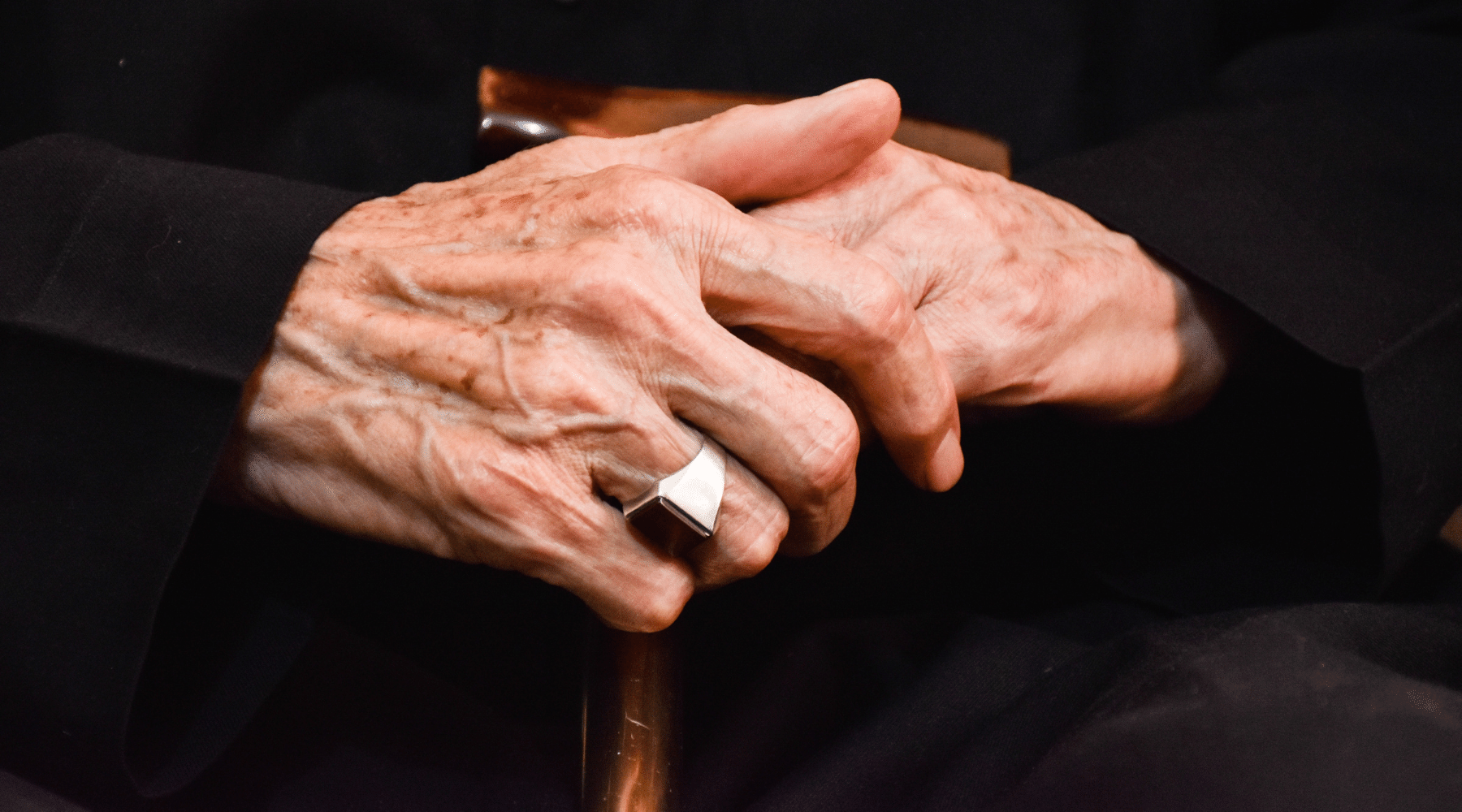

Robert’s dad had long suffered from Type I diabetes, which he’d managed through a careful combination of drugs, diet, exercise and medical care. But at 87, the disease had been getting the best of his body for some time. He felt miserable.

Robert’s dad had long suffered from Type I diabetes, which he’d managed through a careful combination of drugs, diet, exercise and medical care. But at 87, the disease had been getting the best of his body for some time. He felt miserable.

“If I just went to sleep and didn’t wake up,” he told his wife and son that morning, “that would be ok.” He explained the only thing that got him out of bed each morning was the fear he’d let down his loved ones if he left this world.

He’d enjoyed a loving marriage for more than 60 years. He’d had a fulfilling career and been a doting father and grandfather. “He’d lived a great life,” said Robert. “But he was ready to be done.”

Robert and his mother phoned his father’s long-time physician, who came to their home. He confirmed that Robert’s father’s condition was deteriorating and would not improve.

If Robert’s father ceased taking his medications and stopped eating, explained the physician, the end would come soon. Robert’s father said that he would like to do that. The family called hospice care.

Over the next few days, friends and family came to see Robert’s dad. He remained, said his son, very much himself. Caregivers provided some pain medication to counteract any discomfort caused by stopping his diabetes drugs and food, and he seemed comfortable.

He interacted with his visitors, talking, listening, laughing and smiling. Robert watched as his father spent time with his grandchildren, who hugged him and told them how much they adored him.

Robert thought, if it were me, after a life-affirming experience like that, I’d start eating again. “Does that change your mind?” he asked his dad, hopefully.

“No,” his father answered.

As his father grew weaker, Robert lay next to him in bed. His dad slept for longer and longer, his slumbers growing deeper and deeper. And, finally, one night at 3:15 a.m., when Robert rolled over and checked on him, he’d stopped breathing.

Robert got his mom. They cried together for 20 minutes. Then they called hospice, who came and took Robert’s father’s body.

The process, from that morning with the doctor to a quiet death in the small of the night, had taken just under a week.

“He left on his own terms,” said Robert, who’d held a half-eaten burger the entire time he’d told me the story. “In his own home. No hospital.” No machines. No adult diapers. None of the potential indignities that come when our aging bodies betray us.

“Even in death, he was showing us profound grace and resolve,” Robert texted me later.

At the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, our mission is to help people live longer, healthier lives. But, perhaps, like so much of the healthcare sector, it would behoove us also to focus more on another, equally important part of the equation: the end of life.

“You don’t have to spend much time with the elderly or those with terminal illness to see how often medicine fails the people it is supposed to help,” Dr. Atul Gawande wrote in his excellent book on the subject, “Being Mortal.”

“The waning days of our lives are given over to treatments that addle our brains and sap our bodies for a sliver’s chance of a benefit,” said Gawande. “They are spent in institutions – nursing homes and intensive care units – where regimented, anonymous routines cut us off from all the things that matter to us in life.”

Unlike most, Robert’s dad was spared this fate. Or, more accurately, he took matters into his own hands and spared himself.

In his final days, he told Robert about an envelope of cash he’d socked away in a desk. Be sure to take it and put it to good use, he instructed his son.

And Robert has. One by one, he’s been donating the neatly stacked $100 bills to local charities. “It’s what my dad would have done.” He smiled. “And every time I give one away, it makes me think of him and how much I love him.”

—

Adam Cohen is OMRF’s senior vice president & general counsel and interim president. He can be reached at contact@omrf.org. Get On Your Health delivered to your inbox each Sunday — sign up here.