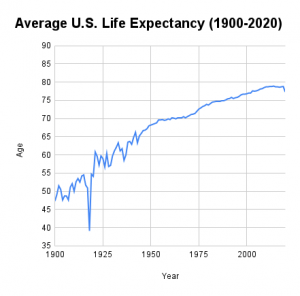

In the United States, we’re used to curves that go in one direction over time: up.

Think stock markets. Household income. Life expectancy.

My grandparents born in the U.S. in 1900 could expect to live 47 years. By 2000, the year between the birth of my two sons, that number had climbed to almost 77 years.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, we can thank public health advances for 25 of those added 30 years. The CDC cites a list of 10 factors largely responsible for this jump, topped by things such as vaccinations, improvements in vehicle safety, safer workplaces and control of infectious diseases.

Not surprisingly, recent years have seen those gains level out. With most of the low-hanging fruit already picked, continued progress has proven more challenging. From 2000 to 2014, the average life expectancy in the U.S. climbed by only two years.

Over the next five years, we saw no increases at all. Experts attributed this plateau (really, a small dip followed by a slight rebound) to the opioid epidemic and other so-called deaths of despair, with any health gains offset by suicide and addiction deaths.

So, some of us may have grown accustomed to the dispiriting prospect that our children may not outlive us, or at least not by much. Still, that doesn’t make the latest life expectancy data – released by the government on Wednesday – any easier to swallow.

According to the National Center for Health Statistics, in 2020, life expectancy in the U.S. dropped by almost two years. Now at 77.3 years, it’s essentially the same as it was 20 years ago.

Covid-19 accounts for most of this drop, the largest since World War II. The rest was largely attributable to overdoses, homicides, diabetes, chronic liver disease and cirrhosis.

That’s quite a bleak picture.

Fortunately, experts do expect the lion’s share of this drop to become a statistical blip, disappearing as we put the pandemic behind us. For example, in 1918, the flu pandemic shaved a whopping 11.8 years off U.S. life expectancy, and the number rebounded fully the following year.

However, this time around, variants such as delta and accompanying resurgences in cases and deaths will likely slow that process. And with vaccination rates varying widely, we can expect further echoes of a trend we’ve already seen with the virus: disproportionate effects on certain communities.

In 2020, life expectancies dropped most among the Latinx community, which lost an average of three years. Black Americans felt a similar impact, with a loss of 2.9 years. Meanwhile, white people’s life expectancies decreased by only 1.2 years.

In Oklahoma, we enjoy a Covid-19 vaccination rate of about 40%. With only 2 out of every 5 people fully vaccinated against the virus, we can expect ongoing mortality effects in those areas – rural communities; those heavily populated by people of color – where inoculation numbers remain stubbornly low.

Of course, even pushing aside the impact of the virus, our state’s health picture has considerable room for improvement. As The Oklahoman reported earlier this week, among the 100 most populous cities in America, the American College of Sports Medicine’s American Fitness Index ranked Tulsa 99th and Oklahoma City dead last for fitness. Key contributors to these rankings were low rates of exercise, along with high rates of smoking, high blood pressure, obesity, diabetes and heart disease.

Often, we seek solutions to health problems in the form of a pill. And scientists at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation and around the world devote their careers to developing a deeper understanding of and new treatments for human disease.

Nevertheless, for so many of the health challenges that cut decades from our lives, we already know the answers. Exercise regularly. Eat a diet high in fruits, vegetables and fiber. Take it easy on the processed foods. Don’t smoke. Drink only in moderation. When faced with addiction or mental health crises, don’t try to go it alone.

For most of us, there’s no magic bullet we need to add years to our lives. It’s simply a matter of making better choices.

With the pandemic, the situation is now quite similar. Vaccines are available everywhere, and most have proven extremely effective at preventing infection, severe illness and death, even when it comes to the new variants. Side effects are very rare.

This past week, the stock market shuddered briefly as it processed news related to the delta variant. Maybe that economic recovery wouldn’t be as V-shaped as experts had predicted.

Let’s hope that’s not the case. And, likewise, we’ll look for the U.S. life expectancy curve to bend its way back upward soon. But, really, that’s up to us and the choices we make as a country.

–

Adam Cohen is OMRF’s senior vice president & general counsel and interim president. He can be reached at contact@omrf.org. Get On Your Health delivered to your inbox each Sunday — sign up here.