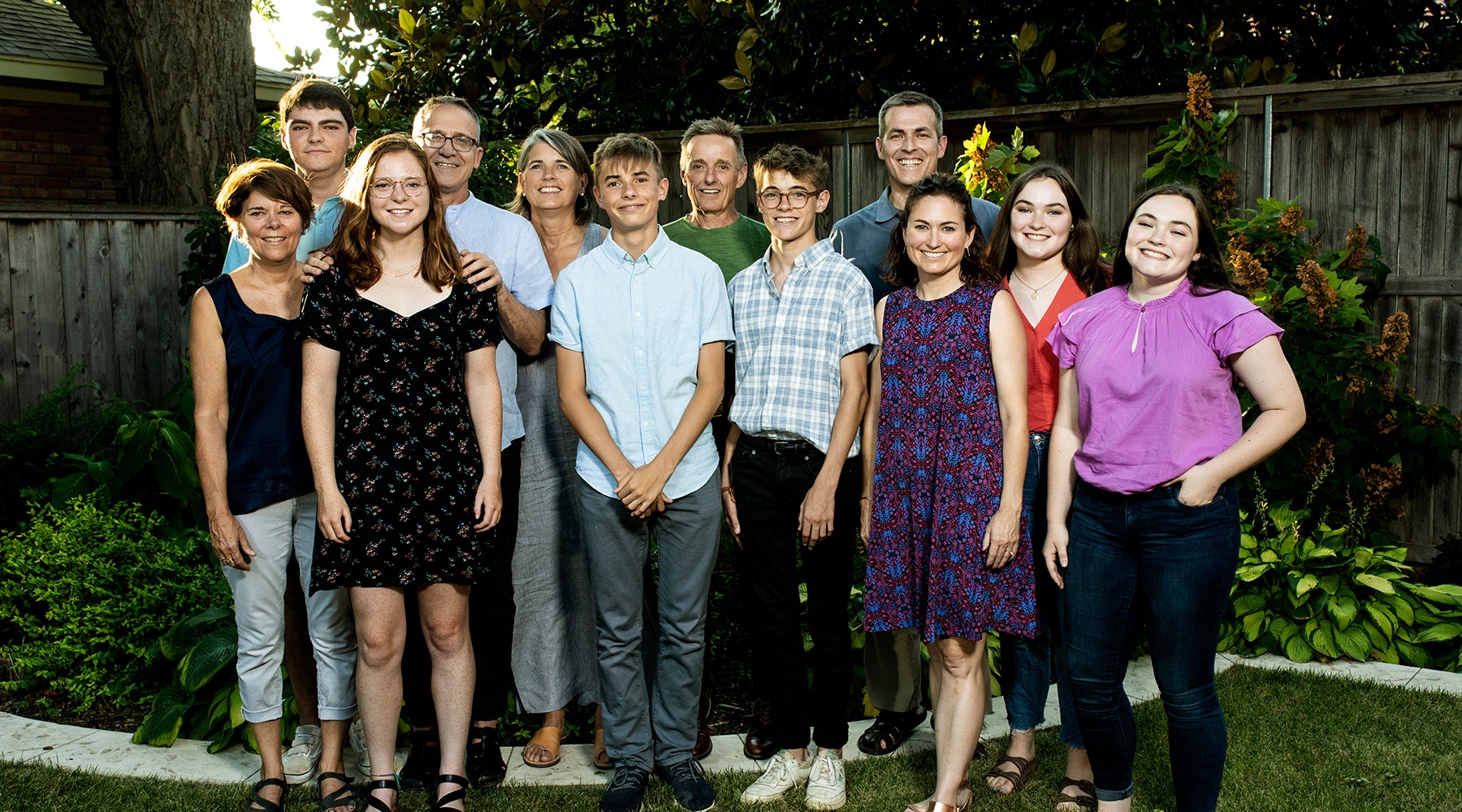

Three Pairs of OMRF Scientists, Three Sets of Twins

Dr. Susannah Rankin remembers when her twin sons, Grady and Zeke, first realized they were separate beings. She and her husband, Dr. Dean Dawson, each took one boy, then only a few months old, from the crib they shared and stood a few feet apart. The infants looked around until they locked eyes on one another. Baby grins and giggles followed. “It was kind of like a game of peek-a-boo,” she says. “It was super cute.”

By 2006, the boys, then 3, had swapped their shared crib for separate beds, and their parents—both cellular biologists—had moved from labs in Boston to OMRF. Once in Oklahoma, the researchers found a ready-made playdate for Zeke and Grady: Drs. Susan Kovats and Pepe Alberola-Ila, who’d come to OMRF the previous year, also had young twins of their own. When Drs. Courtney and Tim Griffin joined OMRF in 2008, it marked the foundation’s third straight joint faculty recruitment where the couple brought not only sterling scientific credentials, but also a set of twins.

The kids were all within two years of one another, and the three families became fast friends. In the ensuing decade, they’ve shared Christmases and New Year’s Eves, sent the kids to many of the same summer camps, and spent countless hours together. “It’s been really special, because none of us have families nearby,” says Tim Griffin. “So, this is like our extended family.”

Being scientists, the parents couldn’t help but make the stray “nature versus nurture” observation when their children shared (or didn’t) certain behaviors or traits. But, mostly, says Susan Kovats, raising twins “helps take you away from the stress of research.”

Having two children at once, says Kovats, “certainly was more efficient.” Still, none of the parents miss the “chronic” sleep deprivation that came with caring for two babies. “I remember driving to work and literally falling asleep at traffic lights,” says Courtney Griffin.” Each of the couples divvied up the child-rearing tasks, which helped ensure they’d have ample—or at least enough—time to pursue their research.

As they grew, the kids learned to keep the drama to a minimum at certain times. “We see how much stress our parents are under when they’re writing grants,” says Olivia Griffin. That’s when they stay up until the wee hours, says Isabel Alberola, “clacking on the computer.”

As the offspring of scientists, the twins have enjoyed a slightly different perspective on life than their peers. Bringing tanks of frogs to class to explain genetics seemed pretty normal. Ditto when your mom lights junk food on fire in order to demonstrate its fat content. And no one seemed surprised when the parents swapped out candy for math problems, word games and trivia at the annual Easter egg hunt.

This fall, Zeke and Grady Dawson and Delancey and Olivia Griffin will all be juniors at the Classen School of Advanced Studies. Meanwhile, the Alberolas will head to college, with José attending UCLA and Isabel off to Barnard College in New York.

The transition may prove tough for their parents, not to mention the quartet of twin friends they’re leaving behind. But it looks like OMRF scientists will continue seeing double: This past year, Drs. Bob Axtell and Rose Ko welcomed twin baby boys, Oliver and John. If the past is any indicator, they should have no trouble finding playmates.