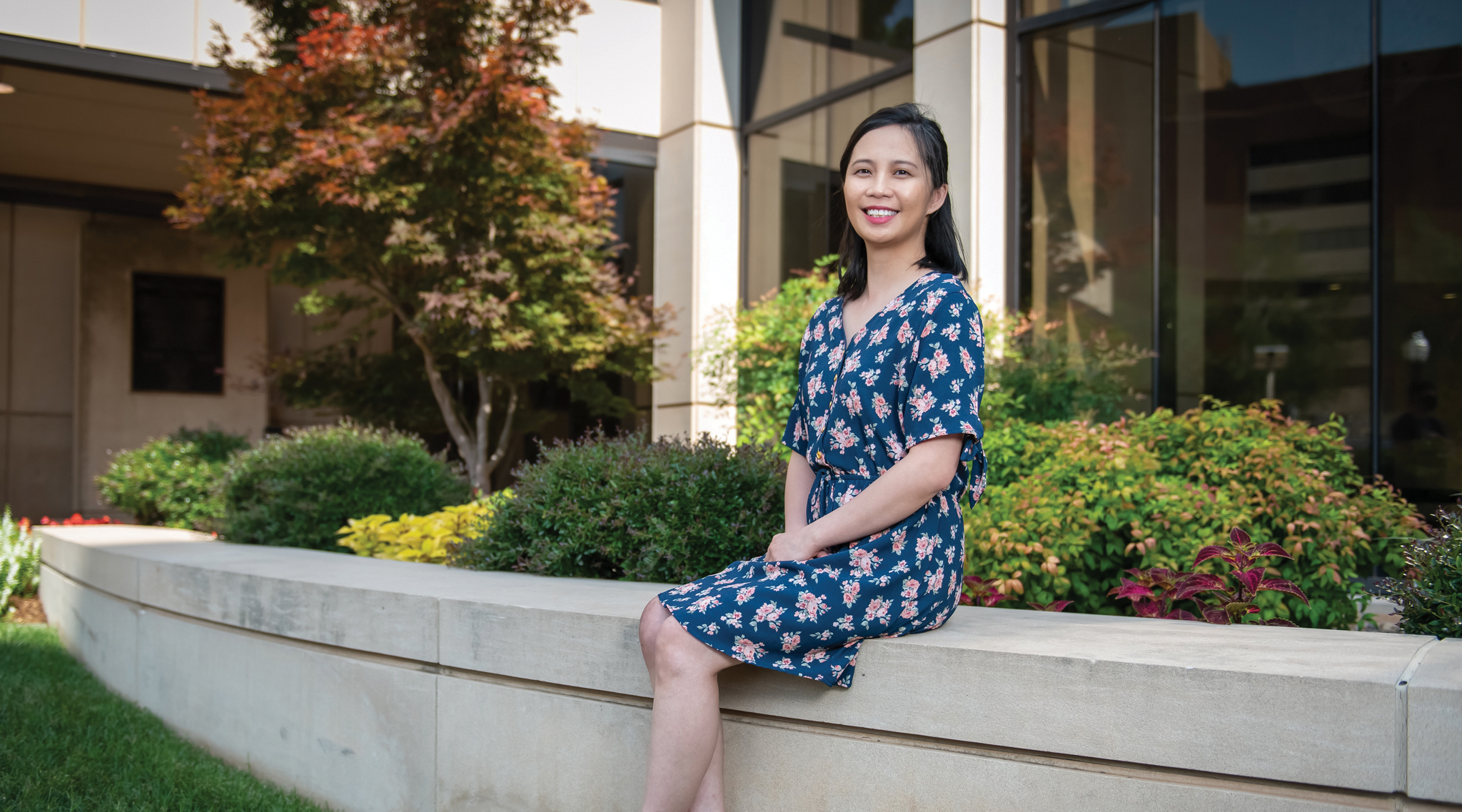

Jennifer Chan will never forget her first visit to OMRF.

It was almost two decades ago, and the foundation was renovating the Rheumatology Research Center of Excellence. Caregivers were temporarily seeing patients in a mobile clinic in the parking lot.

“It was a trailer,” she laughs. “But it was a light at the end of the tunnel. I saw I could have a normal life.”

Three years earlier, Chan’s doctor diagnosed her with lupus, an autoimmune disease that strikes women at disproportionate rates.

Lupus occurs when the immune system becomes unbalanced, leading to antibodies and chronic inflammation that damage the body’s organs and tissues. People with the condition experience periodic disease flares, affecting organs that can include the kidneys, lungs, skin and joints, and the cardiovascular system.

Chan, of Oklahoma City, was 14 years old when her symptoms first appeared. Six months passed before she learned the cause of her chickenpox-like rash and an unrelenting, seizure-inducing fever.

“It was scary,” says Chan, now 36. “But I decided if my body was going to fight me, I was going to find a way to fight back.”

That path led to OMRF’s Dr. Joan Merrill. A physician-scientist, Merrill was devoted to caring for patients like Chan. But she also wanted to be immersed in research to transform the landscape of lupus diagnosis and management.

At Columbia University, where Merrill worked as a rheumatologist prior to coming to Oklahoma, she was too busy with patient care to study the disease. At OMRF, she could do both. “My entire job was the thing that I’d always dreamed of doing,” she says. “I could see patients, and almost all of it was about research.”

The centerpiece of that research was the Oklahoma Lupus Cohort, which Merrill established at OMRF in 2001. Known today as the Oklahoma Cohort of Rheumatic Diseases, it’s a collection of tens of thousands of blood, urine, saliva and tissue samples donated by research volunteers. Researchers at OMRF have used those samples to delve deeper into lupus, and they’ve also shared them with research collaborators at dozens of institutions around the world.

All told, the samples have contributed to more than 500 research studies published about lupus. And since the birth of the cohort, three new medications for lupus have earned Food and Drug Administration approval. All went through clinical trials at OMRF, tested by cohort patients.

For patients like Chan, participating in research presents a chance for empowerment, an opportunity to turn the tables against a disease that too often wreaks havoc on their lives.

“I was practically beating down the door to join the cohort,” she says. Chan imagined the possibility of having a younger sibling or a child with lupus. “I wanted the future to be better for them.”

And today, says Merrill, it is.

“The downstream effect of the growing knowledge base is earlier diagnosis, flare prediction and intervention, and customized treatment,” says Merrill.

A 2021 analysis published in the journal Environmental Research and Public Health found that OMRF leads the U.S. in research productivity on systemic lupus erythematosus, the most common form of the disease. Over the past half-century, the foundation has contributed to more research papers on the disease than any other institution in the nation – nearly 10% of all lupus studies have a foothold at OMRF.

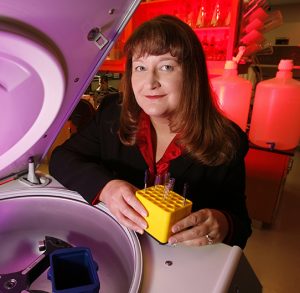

That’s attributable in no small part to the cohort, says OMRF Vice President of Clinical Affairs Dr. Judith James. Beyond its worldwide contributions to the understanding of lupus, James says the cohort fundamentally shifted research at the foundation.

“It opened our eyes that we could do different kinds of science here,” says James.

Recently, that has included progress on what James calls “the cutting edge of precision medicine for lupus.” Her lab collaborated with Merrill last year to publish new research that, through studying years of blood samples from cohort patients, showed how lupus changes at the molecular level over time.

“We have never been able to do that,” says James. “That may help us as we pick the right treatment for a patient.”

Merrill also pioneered novel clinical trial designs to improve testing new therapies for lupus. “We hadn’t done investigator-initiated clinical trials at OMRF before Dr. Merrill,” says James.

In those studies, a scientist at a research institution like OMRF, rather than at a pharmaceutical company, develops and leads the trial efforts.

One study Merrill designed revealed that to test new lupus drugs effectively, doctors must first scale back patients’ current medications. The Lupus Foundation of America called the work “precedent setting.”

Merrill feels certain that OMRF’s environment, which blends clinical and lab research with world-renowned experts in autoimmune disease, has allowed the cohort to thrive. “It would have never had the same impact without OMRF,” says Merrill. “It was the conjunction of planets.”

The trailer-turned-clinic where Chan first met Merrill is long gone. One day soon, Chan believes, lupus will join it in the scrap heap of history. “If not in my lifetime, it will be solved for future generations,” she says. “Because of research.”

For information on joining OMRF’s lupus studies, call 405-271-7745 or email clinic@omrf.org.

—

Read more from the Winter/Spring 2022 issue of Findings

Family Matters

Lessons in Philanthropy

Go East, Young Man

Hitting the Target

How Yellowstone’s hot springs paved the way for DNA testing

Voices: Nancy Yoch

Strange Things