Putnam City Schools has raised millions to support cancer research at OMRF. And they’re not done yet.

It started with love. And loss.

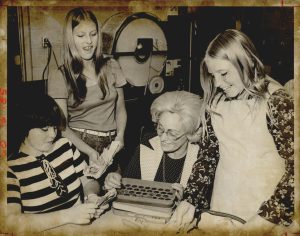

The year was 1974, and Lois Thomas, a Putnam City High School journalism teacher, was grieving the death of four dear colleagues and the recent diagnosis of the district’s superintendent, Leo Mayfield. The common thread? Cancer.

In her youth, Thomas had gone door to door to raise funds to combat polio for the March of Dimes. So, she made up her mind to start a similar effort to fight another disease that touches so many.

Thomas, with the help of fellow journalism teachers throughout the district, organized a change drive, and soon a legion of Putnam City students were canvassing their neighborhoods to fight cancer. When word of the campaign got out, charities deluged Thomas with phone calls, hoping to benefit from the effort. But when she learned that OMRF performed cancer research, “I called them up,” she said in a 2006 interview. “I asked them, ‘What’s the chances of my school collecting money for cancer and giving it all to you?’ They said, ‘Absolutely, you can do that.’ I said, ‘Put me down.’”

Thomas also wanted to ensure none of the funds they collected would be diverted to administrative costs. “The Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation pledged that all of the funds would go to research,” Thomas remembered in a 2003 interview with this magazine. “That’s why every penny we’ve ever collected has gone to OMRF.”

“Mom was a pretty high-energy, get-’er-done kind of person,” says her daughter, Carolyn Churchill. “She wouldn’t stop until it was done and done well. She really did think, ‘If everybody gave pennies, look how much money that would be.’”

Thomas’ brainchild has led to what may be the longest-running school district-cancer research partnership in history. Since an inaugural donation of $24,000, Putnam City Public Schools has raised more than $3.8 million for cancer research at OMRF.

Those funds reflect the efforts of hundreds of thousands of Putnam City students, teachers and staff members. They also point to how one school district has cultivated, nurtured and sustained a culture of giving across multiple generations. In that time, a simple coin drive has mushroomed into much more: a massive effort that includes bake sales, car washes, crazy hat days, dunk tanks, garage sales, carnivals, taco suppers, benefit concerts, 5K runs and countless other student-driven activities.

—

Thomas’ granddaughter, Becky Landry, remembers her grandmother visiting schools regularly to promote the Cancer Fund Drive after her retirement in 1981. She continued the practice until the spring before her death in 2007.

“She’s the only person I know who could get everybody in that gym to be quiet,” says Landry, who taught at Putnam City West. “She’d just put her fingers up to her lips, and you could hear a pin drop with all the kids in there.” Landry also recalls the competitive spirit of the Cancer Fund Drive, and her grandmother’s irritation any time PC West’s Patriots raised more than her beloved Pirates of PC “Original.”

In one of the drive’s early years, cafeteria staff sold homemade cinnamon rolls and donated the proceeds, baking their way to a $6,000 contribution. Since the 1980s, the district has contracted with Sodexo for cafeteria services, and PC Superintendent Dr. Fred Rhodes recalls a year when dozens of Sodexo staffers signed up for the Cancer Classic run. Like every other event in the drive, proceeds from the annual 5K go to OMRF.

Fundraising reaches a fever pitch every spring at the district’s three high schools, when students participate in a weeklong series of events culminating in a carnival. It’s easy to understand why, considering the collective energy of the more than 5,000 students that attend PC Original, PC West and PC North.

“I didn’t know what it was or what to expect,” says Brett Bradley, lead principal at PC Original. “And then when I experienced my first one, it was amazing.”

Over the years, he says, the Pirates have developed a formula that works. Think “Crazy Olympics” competitions between students and faculty. Or tugs of war, relays and “chariot” races, where two people pull a third splayed on a sheet. Food trucks and restaurant vendors add to the festivities – and fundraising.

After Covid-19 forced carnival cancellations the past two school years, students are working hard to bring the tradition back in spring 2022. Seniors Shyla Woody and Kaleb Whitaker are helping to lead this year’s campaign at PC Original. Both have a personal stake.

“When I was in middle school, my mother was diagnosed with stage 3 breast cancer,” says Woody. “It really encourages me to do more. I could see how she struggled.”

Whitaker agrees that fundraising doesn’t feel like someone else’s job when it comes to a deadly disease that affects millions upon millions. “I know countless people at this school who have either dealt with somebody having cancer or dying of it,” he says. “My godmother died of lung cancer right before I entered high school, so to bring awareness to it made me happy and made me want to insert myself in it.”

Michael Hardesty, the school’s activities director, oversees the work of student organizers like Woody and Whitaker. Each year, he says, the Pirates put together a paper chain link with the names of loved ones affected by cancer. “It usually goes clear around the gym floor,” he says. “Everybody knows somebody.”

—

The millions PC Schools has donated to OMRF over the past four-plus decades supports scientists in multiple research programs across the foundation. In a dozen labs, OMRF researchers work to unlock cancer’s mysteries. One of those labs is Dr. Gary Gorbsky’s, whose experiments in the Cell Cycle & Cancer Biology Research Program help illuminate what goes wrong in cancer by understanding how healthy cells typically function.

“We’re trying to write the shop manual about how the normal cell works,” says Gorbsky, who holds the W.H. and Betty Phelps Chair in Developmental Biology. “Cells are so incredibly complicated. We have a lot more to do.”

Scientists at OMRF also focus on translating their experiments into novel experimental treatments for cancer. Dr. Rheal Towner, director of OMRF’s MRI facility, has been studying brain tumors for the past 15 years. He’s no spy, but his collaboration with fellow OMRF researcher Dr. Robert Floyd resulted in an experimental compound partially named for one.

“The drug is called OKN-007,” says Towner. “The 007 was just for fun.”

Floyd originally developed the compound decades earlier in hopes it would help treat strokes. That effort proved unsuccessful, but when he learned Towner had developed a model to study tumor growth in glioblastoma, the most aggressive form of brain cancer, the two joined forces.

Working with Dr. James Battiste, a neuro-oncologist at the University of Oklahoma Health Stephenson Cancer Center, the team of scientists eventually made an important discovery. When the experimental drug was combined with the usual standard of care for glioblastoma, OKN-007 prevented the fast-moving chemotherapy resistance commonly associated with the drug temozolomide.

In clinical trials in patients, says Towner, “We’re now extending overall survival beyond 22 months with that combination,” nearly doubling the usual life expectancy after a glioblastoma diagnosis. Some patients, says Towner, are now cancer-free. “Enthusiasm for OKN-007 is very high,” he says.

—

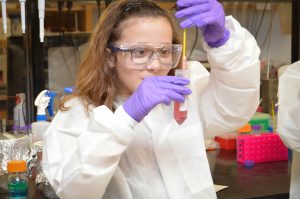

Since 1979, OMRF has thanked its youngest philanthropic partners through the Putnam City Junior Scientist Program, opening its laboratory doors to students from each of the district’s schools for a day of onsite learning and discovery. OMRF has also welcomed 27 students from PC Schools to its Sir Alexander Fleming Scholar Program. Selected from among Oklahoma’s most promising young scientists, Fleming Scholars undertake eight weeks of paid, intensive summer study in OMRF’s world-class research laboratories. On the last day of the program, the scholars formally present their work.

PC Superintendent Rhodes never misses those talks. “We’ve had students I knew as elementary students who are now young adults,” he says. “They’re presenting their research, and it’s just awesome.”

Rhodes’ own philosophy has been integral to strengthening the PC-OMRF partnership in recent years.

“What we learn in school is so much more than the reading and math and writing and academics we get grades for,” he says. “Our job as educators is to foster within a child everything we can to prepare them for their future. If we can create the desire within a child to give back to the community, then I feel like we have accomplished so much more. OMRF fits that.”

And to think, he says, “It started with one teacher.”

—

Read more from the Winter/Spring 2022 issue of Findings

Family Matters

Go East, Young Man

Hitting the Target

Life Changer

How Yellowstone’s hot springs paved the way for DNA testing

Voices: Nancy Yoch

Strange Things