To understand Dr. Andrew Weyrich, it helps to get to know Sam.

Sam Weyrich, Andy’s son, came into this world uneventfully. Doctors administered Apgar tests as soon as Sam arrived. Heart rate: normal. Muscle tone: normal. Respiration, reflexes, appearance: check, check, check.

But a few months into his young life, Sam started crying. Not just typical infant mewling, he wailed inconsolably and nonstop. Then, his parents noticed his eyes weren’t tracking light or objects.

Doctors first suspected blindness. But an MRI led to a devastating diagnosis: Sam had been born with a rare condition known as a leukodystrophy.

The myelin sheath, the fatty insulation that covers nerve fibers, hadn’t developed properly. Without that protective layer, leukodystrophy patients have decreased motor function, muscle rigidity and eventual deterioration of sight and hearing. The disease is fatal, with no cure and extremely limited treatment options.

“They basically told us, ‘Go home and enjoy him,’” says Amy Weyrich, Sam’s mother and Andy’s wife. “His life expectancy was two years.”

The diagnosis understandably staggered his parents. “You always think your children are going to outlive you,” says Andy. But he and Amy quickly made a pact. “We decided we were going to try to be phenomenal parents to Sam during his time, however long that was.”

That was 21 years ago.

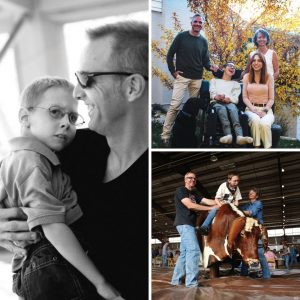

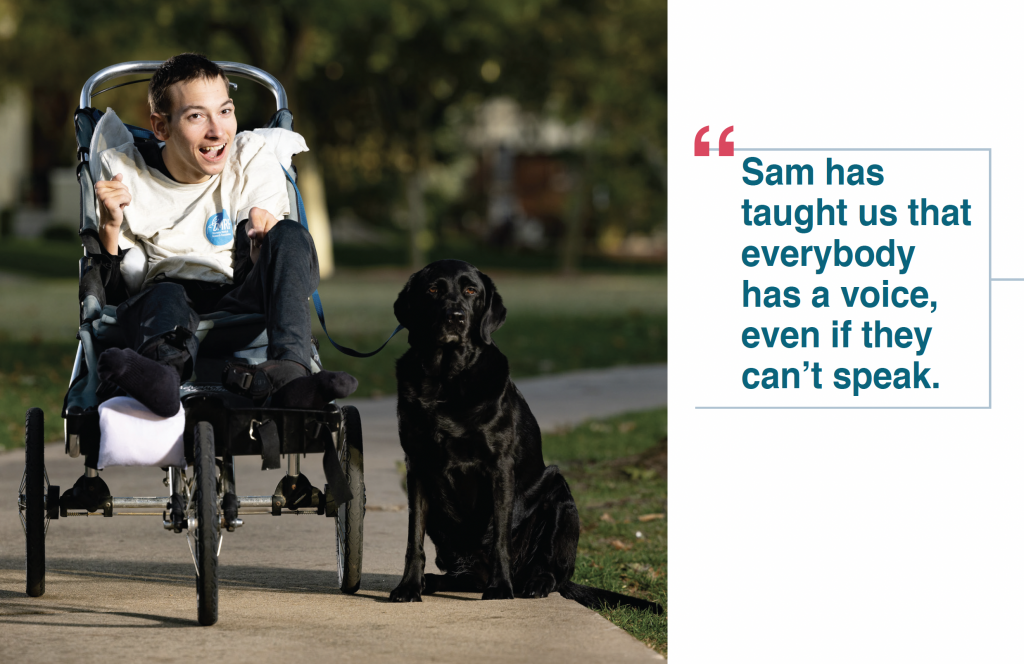

Since that time, Sam – with a lot of help from Amy and Andy, as well as from Sam’s older sister, Sarah – has grown up. If you met him, you might observe that Sam doesn’t walk or talk. That his limbs are so weak he cannot raise his hands or even grasp objects. That he spends his life in a wheelchair, his every need attended to with great care by his mother and father.

Andy, though, would say you are missing the point.

“Sam has taught us more than we could have ever imagined,” says Andy. As their son’s life stretched beyond expectations – into elementary school, then his teens, now his 20s – the Weyrichs learned to ignore predictions and, instead, focus on what they could do to improve the odds.

They also grew to understand what it meant to listen in a world where, too often, the loudest noises drown out all others. “Sam has taught us that everybody has a voice,” says Andy, “even if they can’t speak.” Andy and Amy trained their gaze on every dart of their son’s eyes, each twitch of his head, to understand his subtle, nonverbal language. It wasn’t that Sam wasn’t talking; it was simply that the world wasn’t listening.

And as Andy and Amy grew to understand their son’s messages, they found he conveyed joy in even the tiniest of gestures. “Sam loves everybody. He doesn’t distinguish,” Andy says. That lesson of unconditional acceptance provided a signpost for Andy in every aspect of his life.

Over time, the Weyrichs also figured out that, despite Sam’s fragile shell, he was no egg. He enjoyed adventures, novel experiences. He went skiing and horseback riding, even took a five-day raft trip in the Grand Canyon. “That trip stressed us in a lot of ways,” says Amy. “But from the moment we got there, he was on. He loved every minute of it.”

Soon after Andy took the job as OMRF’s president, he and Amy brought Sam to Oklahoma City. They wanted him to see the place that would become his new home.

On most weekends, Andy takes Sam running. Often, they’ll share a pair of AirPods, so that father and son can enjoy the same music.

But this time, Amy joined them, and they left the music behind. “Andy wanted to talk to him about the place,” says Amy. As they jogged, Andy provided commentary, pointing out landmarks – Scissortail Park, the Wheeler Ferris Wheel, the Devon Tower. Throughout, Sam stayed attentive to his father. “His head was up, he was smiling, he was looking around,” says Amy.

What Sam couldn’t say in words, he spoke with eyes. His grin. The effort it took for him to hold his head up for an hour as Andy pushed him through midtown and downtown Oklahoma City.

Dad, he seemed to say, I couldn’t be more excited for this new adventure.

Andy grew up outside of Columbus, Ohio, the son of an Episcopal priest and a real estate professional. From an early age, he remembers his parents’ commitment to social justice and the civil rights movement. At the age of 5, Andy recalls his family delivering food and supplies to the Black Student Caucus, a group of his father’s fellow divinity students who staged a 19-day lockdown of the school in 1968 that resulted in more Black representation on the faculty and board of trustees and the creation of a Black Church Studies program.

In addition to regularly volunteering at food pantries and homeless shelters, he and his two brothers also devoted a good deal of their extracurricular time to basketball and baseball. All three went on to play baseball at the collegiate level.

Andy attended Baldwin Wallace University in Ohio. As a middle infielder and, eventually, a first baseman, he earned Academic All-American honors. “I wish it was because I’d been a better baseball player,” he says, “but it was really more due to my academics.”

Growing up, he says, math and science had always come naturally to him. “I was good with flashcards, and I enjoyed those subjects a lot.” In college, he majored in biology. He didn’t know exactly where his studies would lead him, so, like many undecided students approaching the end of their undergraduate careers, he applied to graduate school. When he received an offer to join the master’s program in exercise and health science at Wake Forest University in North Carolina, he jumped at it.

There, he focused on cardiac rehabilitation, working with patients recovering from heart attacks, strokes and various procedures. He also spent time with athletes, testing them for exercise performance thresholds. He enjoyed the interaction with patients, he says, “but I discovered my real passion was for the science.” So, he decided to pursue his Ph.D. at Wake Forest’s Bowman Gray School of Medicine.

Harkening back to his days on the diamond, he published his first paper on baseball and kinesiology. “We were looking at how balls came off a wood bat versus an aluminum one,” he says. He also continued to study the physiology of endurance athletes as they pushed their bodies to the edge. Soon, though, those efforts took a backseat to lab work.

In the laboratory, he immersed himself in the mechanics of blood clotting. He earned his doctorate in physiology and pharmacology, then accepted a postdoctoral fellowship at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia. But he didn’t go alone.

In graduate school, he’d begun dating Amy, who earned her master’s in the same program. Another former collegiate athlete – she’d played field hockey at the College of William & Mary – Amy had grown up in New Jersey, just across the bridge from Philadelphia. The couple got a place in New Jersey and married the next year.

Each day, Andy commuted into the city, where he studied molecules found in the blood, known as selectins. That work led him to a second fellowship, this time at the University of Utah. And that’s where he first came to the attention of Dr. Rodger McEver.

McEver had joined OMRF a few years earlier, and he, too, studied selectins. He’d established a research collaboration with a group of scientists in Utah that included Andy’s mentor. As part of that partnership, McEver traveled to Utah and sat in on lab meetings.

“I heard Andy present his work in 1993,” recalls McEver, who is now OMRF’s vice president of research. “My impression was that he was very intelligent and had a calm, articulate way of expressing himself.” As is often the case in science, the discussions proved “lively,” says McEver, with researchers challenging each other’s hypotheses and findings. “Andy took feedback well. He would listen to advice and ideas.”

McEver struck up an ongoing research collaboration with Andy, publishing several papers with him over the years. “I thought, ‘This is a sharp guy. He’s going to do well.’”

And he did. Andy shifted his research focus to platelets, cells that circulate in our blood and bind together when they recognize damaged blood vessels. He delved into how platelets communicate with other cells. In the process, he discovered that platelets, previously thought to be inert – “like a sack of glue,” says Andy – actually altered their genetic makeup in different inflammatory diseases. “That meant they don’t just act the same all the time,” Andy says. That discovery had profound implications for managing illness in patients.

It also represented a major shift in how researchers understood blood clotting. The change was so profound that, at first, Andy didn’t even believe his own results. But when he continued to redo his experiments and get the same outcome, a mentor urged him to have confidence in his work. “He said, ‘You have to believe your own data,’” Andy remembers.

Eventually, he did. And not long after, the cardiovascular biology world caught on, too. “I’m amazed to see all the follow-up work people have done. Those initial studies turned out to be super impactful,” says Andy.

Andy published the work in some of the world’s leading scientific journals. “He made a big splash with those papers,” says McEver. “But when you have new observations, you better be sure they are correct.” Decades later, says McEver, the findings have held. And that pioneering work, he says, “opened a new avenue for understanding blood clotting, inflammation and infectious disease.”

On the strength of this work, Andy climbed Utah’s academic ladder, first as a research professor, then as a faculty member who would earn tenure and an endowed professorship. Still, the path forward would not always prove smooth.

—

Amy and Andy had their first child, Sarah, in 1998. Two years later, they had Sam. Despite Amy and Andy’s resolve to make the best of the situation, at times, it overwhelmed them. “I remember closing my office door on multiple occasions and crying,” Andy says.

The Weyrichs struggled to understand Sam’s condition and care for their infant son, who, at that time, wasn’t predicted to survive to his preschool years. But Andy also struggled professionally, as his research, while paradigm-shattering, at first failed to garner financial support. “I was still a research professor,” which meant he had no guarantee of continued employment, “so I needed to get funded.” Twice, study sections at the National Institutes of Health rejected his applications for his “R01” grant, a cornerstone award that provides financial support sufficient to run a lab for several years. “I only had one more shot.” Andy reached out to his program officer at the NIH, who asked Andy to send copies of his work. After reviewing the findings, the program officer flipped the light from red to green, funding the grant for four years.

Since then, Andy has enjoyed continuous funding from the NIH, including a prestigious grant known as an R35, a seven-year award established to promote scientific productivity and innovation by providing sustained support and increased flexibility in research. But, he says, that moment at the crossroads never stands far from his mind. “We didn’t think Sam would live. And even though I never lost passion for my work, I had doubts I would be successful as a researcher. Could I make it?” The support he and Amy received, he says, proved crucial. “That’s when our mentors and friends said, ‘We got you.’ That was a turning point.”

Andy has never forgotten what that boost meant, both on a personal and professional level. It’s one of the reasons he’s made mentoring students and research trainees a point of emphasis throughout the balance of his career. “The key is to train the next generation,” he says. “When you see one of your trainees give a talk, get a grant or publish a new finding, that’s one of the most gratifying experiences you can have.”

Dr. Guy Zimmerman, Andy’s former postdoctoral advisor and a longtime colleague in Utah, describes Andy as “an absolutely committed mentor of younger people and developing faculty.” He is, says Zimmerman, “one of the best I’ve worked with.”

With increased funding, over time, he grew his lab to more than 20 people: physician-scientists, Ph.D. researchers, postdoctoral fellows, graduate students, medical students, undergraduate students and technicians. The work they did studying blood clotting touched a multitude of different areas: heart disease, diabetes and stroke. But, mainly, they focused on infectious illnesses and sepsis, the potentially fatal blood condition that infections can trigger.

He published more than 150 research papers, and the University of Utah named him an H.A. and Edna Benning Presidential Endowed Chair, an honor bestowed upon the institution’s top medical researchers. He strove to carry his work from “bench to bedside,” connecting experiments in Petri dishes with patients experiencing medical challenges. That meant testing observations his team made in the lab against blood samples donated by research volunteers.

One of those clinical studies, which examined a therapy currently being used against infection, found evidence that the treatment could also cause tissue damage. He and his team then developed an inhibitor designed to prevent those potentially calamitous side effects. The university licensed the discovery to a biotechnology company, which is now working to create a therapy that could help a range of patients from premature babies to adults suffering from a variety of infectious conditions.

With a well-earned reputation as a collaborative scientist, and one whose work bridged multiple disease areas and connected laboratory researchers with clinicians, Andy eventually joined university administration. A stint helping direct the molecular medicine program led to an appointment as associate dean of research in the health sciences center. Then, in 2016, the university named him vice president for research.

The position oversaw the research portfolio for the health sciences center as well as the entire university, which encompasses 18 different colleges. It also introduced Andy to new realms that included managing regulatory compliance and serving as president of the University of Utah Research Foundation and Innovation District.

As leader of the university’s research community, he spearheaded a series of strategic investments into targeted areas of research. “We created a department of population health,” he says, “and we put money into diabetes, neuroscience, infectious disease and genetics.” He developed new skill sets, working with donors and Utah state officials for funding to support the initiatives. He also made diversity a focus, both within his own leadership team and by supporting new initiatives aimed at changing the complexion of research.

The efforts paid dividends. Under Andy, the university’s total research funding grew from roughly $400 million to almost $600 million annually. Andy loved the work, especially the pieces that linked him with stakeholders not only at the university but beyond.

“Decisions should be community-based,” he says. “I have an open-door policy, and everybody’s voice is important.”

He took pride in what he’d accomplished in nearly three decades in Utah. But he found himself looking to the horizon for a “final step” in his career. Sarah had graduated from college and moved to Chicago to pursue a career in musical theater. Sam, too, had grown up, and he’d soon finish at the school he’d been attending for many years.

They’d built a good life in Utah. Amy, in particular, fretted when she imagined leaving. She worried especially about Sam, about how they’d replace the caregivers and programs that had helped their son beat all the odds.

Still, she knew her husband yearned for a new challenge, an institution to lead. Maybe, she told him, she’d think about it. But only if it’s the right place.

—

In Utah, Andy had worked closely with Dr. Stephen Prescott. A longtime faculty member at the university, Prescott’s research overlapped with Andy’s, first during Andy’s postdoctoral fellowship, then during his early days as an independent researcher. “Steve was a mentor and a great friend,” says Andy. When Prescott left the university in 2006 to become president of OMRF, Andy kept up with him and his wife, Susan.

Through his work, Andy maintained many other touchpoints with OMRF, collaborating not only with McEver but also with other cardiovascular biologists at the foundation. “OMRF is known worldwide for its strength in this area,” he says.

Following Prescott’s death in May, Andy reached out to McEver. “I asked him kind of candidly, ‘Do you think I’d be a candidate?’” remembers Andy. “And Rod said, in his characteristic way, ‘I think you’d be credible.’”

After Andy applied and interviewed via Zoom, a search committee consisting of a dozen members of OMRF’s Board of Directors and National Advisory Council enthusiastically agreed, selecting Andy as a finalist for the position. When he and Amy came to Oklahoma City in September, they were, he says, “blown away.”

“We couldn’t believe the level of community engagement,” he says. “People from across Oklahoma came just to see us. Everyone seemed to coalesce around the mission of the foundation.” In an increasingly fractious world, he found the unified support “refreshing. That’s something you can get excited about pretty quickly.”

Importantly, Amy agreed. “Everybody we met was genuinely kind. I could also see Oklahoma City was an up-and-coming place.” When she toured facilities that served the city’s special needs community, she found a variety of resources to help support Sam.

“When we left, I said, ‘I hope we get offered this job,’” says Andy, “‘because we’re coming.’”

The feeling, says OMRF Board Chair Len Cason, was mutual. “We searched for a visionary scientific leader, and Dr. Weyrich was in a class of his own.” When the Executive Committee of OMRF’s Board of Directors unanimously voted to extend an offer to Andy, he accepted.

OMRF already enjoys “a reputation as home to the best and brightest in research,” says Cason. “We think Andy is going to take us to the next level.”

In November, Andy, Amy and Sam visited Oklahoma City. Although he wouldn’t start officially at OMRF until January, Andy wanted to hit the ground running. So, he’d come to town to meet with OMRF staff and to help his family get familiar with their new home.

In just a few days, the Weyrichs bought a handicap-accessible van and put a down payment on a house that’s “Sam-ready.” They also brought Sam to OMRF to introduce him to the senior leadership team Andy will work most closely with. “Family is at the heart of who I am,” says Andy. “So, it’s important to me that my team gets to know my family.”

Sam, in particular, has provided a larger frame for his work. “At first, I think I was doing research for the sake of research.” But when his son was born, it transformed an intellectual pursuit into something deeper, more meaningful. “Maybe what we learned could help the next generation of Sams.”

That goal – to understand, treat and prevent disease – “is what gets me up and what keeps me going,” he says.

At OMRF, Andy sees a research organization that’s already thriving. So, he says, he’ll aim “to build on that excellence, to amplify and strengthen.” To understand where to focus those efforts, he’ll take a page from what he’s learned parenting Sam. “I need to get out there and listen.” That means seeking input from scientists, staff, Board members, donors, legislators and other members of the community.

The information he gleans from those meetings, he says, will help him sketch the blueprint for OMRF’s future. “I want to set us up for continued success. We want to move things forward so that the excellence here becomes a perpetual thing.”

It’s these sorts of strategic thoughts that will creep into his head when he takes a long run by himself. “I’ll think, ‘What are those innovative things we can do to get us ahead of the game 10 years down the road?’” Those sweaty, meditative sessions have proven invaluable to Andy throughout his career as a researcher and leader.

Still, those workouts will always take a backseat to another set of runs.

“When I’m out there pushing Sam, and he’s smiling and looking around, there’s nothing better in this world.”

—

Read more from the Winter/Spring 2022 issue of Findings

Lessons in Philanthropy

Go East, Young Man

Hitting the Target

Life Changer

How Yellowstone’s hot springs paved the way for DNA testing

Voices: Nancy Yoch

Strange Things