April

The headline in The Washington Post said it all: “A young couple died of overdose, police say. Their baby died of starvation days later.”

The article that followed recounted a tragic story. It was specific to a community 60 miles outside Pittsburgh, and to a young family who lost their lives. But it also represented a much larger narrative, one that’s touched every corner of our country.

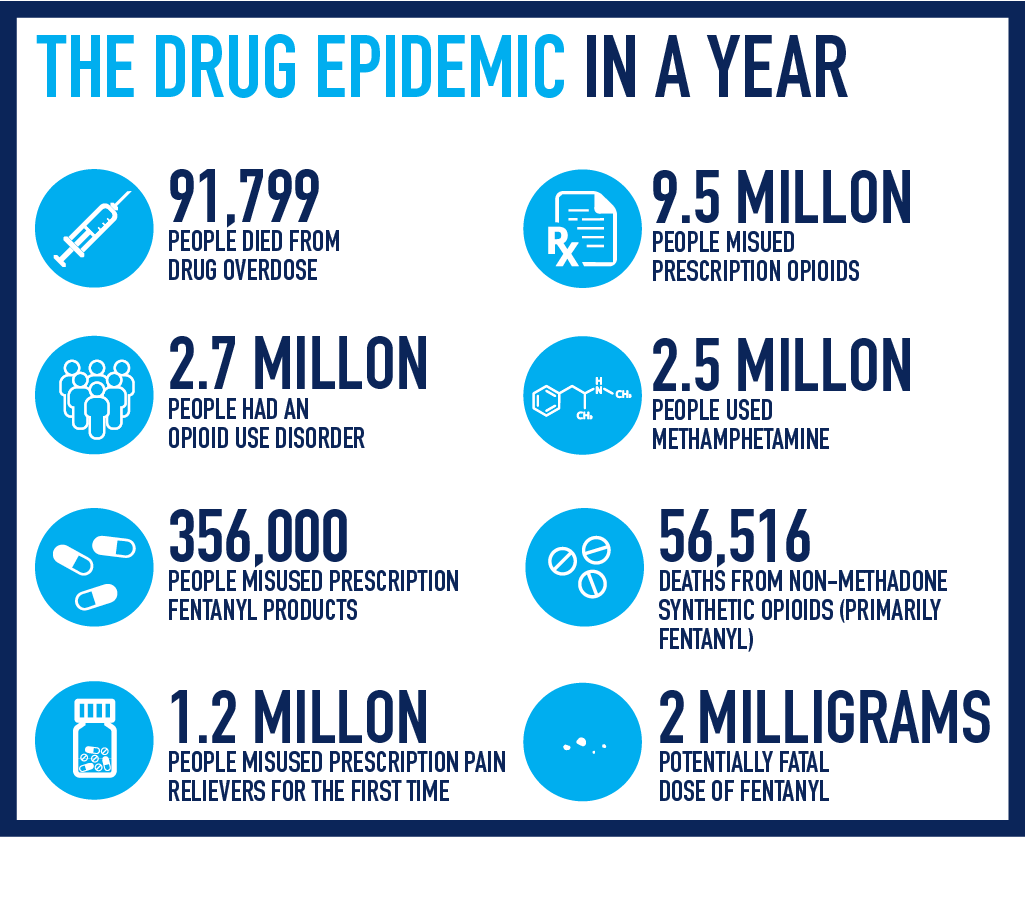

Beginning around 1970 – thanks to declines in smoking, the development of better treatments, lifestyle changes and a variety of preventive measures – most Americans have enjoyed longer and healthier lives. But around 2000, that trend came to an abrupt halt. The culprit? A group of killers economists labeled collectively “diseases of despair”: suicide, alcoholism and addiction to drugs, primarily opioids.

When Nobel Laureate Angus Deaton published a study that put a finer point on the reverse in mortality trends from 1999 through 2013, he wrote, “Half a million people are dead who should not be dead.” By most researchers’ estimates, those numbers have since more than doubled.

From public health experts to surviving family members, countless Americans are now working to change those grim statistics. At OMRF, Dr. Mike Beckstead is leading those efforts.

Beckstead investigates the role dopamine, a naturally occurring chemical in the brain, plays in addiction to opioids and other drugs. In April, he published a study that could clarify a mystery about chemical changes in the brain that occur during relapse. “This may be a missing piece in understanding how increased dopamine activity leads to addictive behavior, particularly after a period of abstinence,” he says.

The finding came on the heels of an announcement that Beckstead had received a four-year grant from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs to continue his work. With the award, he’ll look to isolate specific pathways that respond to opioids without shutting down broader receptors for dopamine, which plays a crucial role in many other systems in the body.

Dr. Bill Freeman, who will work with Beckstead on the project, recognizes that “there’s no magic pill to cure addiction.” But with such an enormous problem to tackle, the pair hope they can help devise at least a small part of the solution.