“Got a call from the police,” read the text from my sister. “Dad called 911 to go to the hospital and is on the way there.”

My father is 91 years old. A retired professor, he lives alone. Despite the efforts of my siblings and me to arrange some degree of in-home assistance and housecleaning for him, he’d resisted.

“I don’t need anybody coming here,” Dad would say. “I don’t want anybody coming here.”

The house was a mess. Newspapers stacked everywhere. Dirty dishes in the sink. Most surfaces coated in varying levels of dust and grime. Mold dotted various walls.

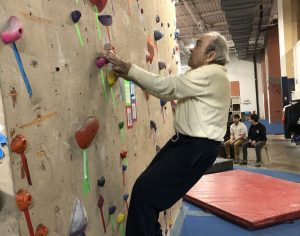

More than a decade before, Dad had suffered a terrible fall at a rock-climbing gym. A seasoned climber, he’d refused to wear a harness, then made his way 25 or so feet up a wall. When he lost his grip, gravity punished him with a broken heel and cracked vertebra. He was fortunate not to end up paralyzed. Or dead.

While he was in the hospital and rehabilitative care, my sister decided to lead a clean-up of his house, which was a wreck even back then. When Dad came home, he was furious at Ali. He stayed that way for years, long after he recovered.

“Apparently, he has a black eye and a bloody elbow from a fall,” read Ali’s new text. “Wish we could figure out a safer living situation.”

I did, too. But none of us wanted to fight with him, and on those occasions when his disheveled, feeble appearance or a call from a concerned neighbor brought the police to his door for a welfare check, he passed muster.

His clothes were stained, his hair wild, his speech slow. Still, when the officers spoke with him, they divined that this was a man in possession of all of his faculties. And, as an emeritus physicist at an Ivy League university, he possessed more than most.

My sister, who lives nearby, would typically hear from an officer at some point in the process. She’d explain that this was Dad’s choice, that he’d consistently spurned our offers of help. The people on the other end of those calls probably thought we were bad, irresponsible children. But none of them did anything.

Until now.

“The social worker from the ER called me,” said Ali. “The police are reporting his house to the county and won’t let him return alone to it as is.”

The news quickly got worse. “Just got a call from the ER,” she texted. “He has a big pulmonary embolism.”

Dad had a major blockage in one of the arteries leading from his heart to his lungs, causing a strain on his heart and restricting the blood flow to his lungs. “They want me to have surgery,” he told me over the phone, struggling between each word for breath. “But I don’t want it at my age.” Instead, he opted for blood thinners to break up the clot.

The next day, as I sat at the gate in Will Rogers World Airport, awaiting my flight to see Dad in Philadelphia, my sister called. She had Dad on speaker, and he’d decided to go ahead with a procedure to protect against any further clots that might get thrown to his heart.

He told us he wasn’t worried about dying. “Whatever happens, it’s okay,” he said. “I’ve had a good run.”

When I saw Dad the next day, a shiner covered half his face, the product of his fall. The procedure had gone well, though, and his clot appeared to be resolving. He’d soon be released to a rehabilitative care facility.

Still, my siblings and I wondered, what happens after that?

At the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, we have an entire research program focused on addressing the declining quality of life as we age. “It’s important that our ‘healthspan’ equals our lifespan,” said Dr. Holly Van Remmen, who leads the program.

The OMRF researchers study cellular phenomena that lead to things like loss of muscle and balance. But what about the other part of the equation, that part that had caused him to give up and no longer care for himself? No pill or exercise routine will put an end to a spiral of self-neglect.

“Unfortunately, we see that a lot,” said the investigator from the county’s Older Adult Protective Services when she interviewed me for my father’s case. I asked if the county could provide us with assistance in remedying Dad’s situation, and she looked at me helplessly. “The case will probably be closed before he gets out of the rehabilitation facility.”

In other words, unless we could convince my father he needed some help, we’d be right back where we started.

According to a 2018 New York Times story, self-neglect is disturbingly common, accounting for more calls to adult protective services agencies nationwide than any other form of elder abuse. Studies in Chicago found it in 7.5 to 10% of the population over the age of 65. But even when it’s reported, as a researcher told the Times, state agencies are “often overworked, understaffed and underfunded.” Plus, with few strategies shown to help, “we really don’t know how to deal with these cases.”

Frightened by the prospect of losing his independence, my father acquiesced, at least for now, to getting his place cleaned up and allowing someone to help with day-to-day tasks like cooking, laundry and shopping. Ali found a cleaning service. But efforts to secure in-home assistance have so far come up short, likely due to the tight labor market.

When I said goodbye to Dad, he was propped up in bed, his head listing to the side. His feet hadn’t touched the ground in days. For years, he’d clung stubbornly to his independence, resisting all forms of help. And now he seemed completely helpless.

I told him I loved him and, reflexively, that everything would be alright. I knew the first part was true. I wanted to believe the second.

—

Adam Cohen is OMRF’s senior vice president & general counsel and interim president. He can be reached at contact@omrf.org. Get On Your Health delivered to your inbox each Sunday — sign up here.