A new Alzheimer’s drug. That has always been the dream.

So, when the Food and Drug Administration green-lit a new treatment from Biogen earlier this month, you’d have expected streamers and champagne. But in many circles, the approval of aducanumab – which will be marketed as Aduhelm – provoked only Bronx cheers.

“This might be the worst approval decision that the FDA has made that I can remember,” said Dr. Aaron Kesselheim. On the heels of the drug’s approval, the Harvard professor of medicine resigned from the independent committee that advised the agency on the treatment.

Of the 11 experts on the committee who reviewed the clinical trial data for the drug, 10 voted against its approval, while one remained uncertain. They said the recommendation was based on their conclusion that the data failed to demonstrate that the drug slowed cognitive decline. Despite this near-unanimous objection, the FDA okayed Aduhelm.

“Approval of a drug that is not effective has serious potential to impact future research into new treatments that may be effective,” said another member of the committee, who also resigned in the wake of the FDA’s decision. “In addition, the implementation of aducanumab therapy will potentially cost billions of dollars.”

Following Aduhelm’s approval, Biogen announced the drug would carry a price tag of $56,000 a year. Led by the Alzheimer’s Association, patient advocacy groups had lobbied strenuously for the drug, which will be administered intravenously each month. But as soon as Biogen revealed the drug’s pricing, the Alzheimer’s Association called the decision “simply unacceptable,” saying that the drug’s cost would be an “insurmountable barrier” to patient access.

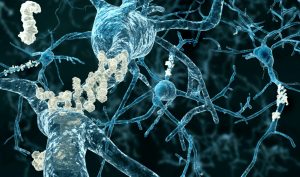

Aduhelm is the first new treatment for Alzheimer’s since 2003, and the only one directed at stopping the disease’s underlying progression rather than simply allaying symptoms. Like research done for many years by the late Dr. Jordan Tang at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, it targets the amyloid plaques found in the brains of those with Alzheimer’s. However, studies thus far have yielded little evidence that attacking these plaques helps combat the disease.

A data safety monitoring board halted two large clinical trials of Aduhelm in people with early-stage Alzheimer’s after it determined the drug didn’t appear to be working. But in a subsequent analysis of trial data, Biogen found that in one trial, the highest dose of the drug had slowed cognitive decline by 22%, or roughly four months over a period of 1½ years. In the other trial, the high dose showed no effect.

“One study was positive, and one identically performed study was negative,” said a Mayo Clinic neurologist who’d worked on the trial. “I don’t think it takes a Ph.D. in statistics to see that that’s inconclusive.”

Nevertheless, the FDA gave the drug the thumbs up, not only in those with early-stage Alzheimer’s but in anyone with the disease. A senior official at the agency stated that “there is substantial evidence that Aduhelm reduces amyloid beta plaques in the brain and that the reduction in these plaques is reasonably likely to predict important benefits to patients.”

Not surprisingly, with 6 million Americans currently living with Alzheimer’s, industry analysts are predicting the drug will be a blockbuster. Several have forecast revenues that will reach $7 billion or more within four years, and those estimates are based on market penetration of only 8% to 10% of patients.

Insurers have yet to say if they will cover the drug. But they will likely follow the decision of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, which is now reviewing the FDA’s decision. If Medicare covers the drug, experts predict it will soon become the most costly medication in the Part B program, which covers drugs administered in outpatient settings like doctor’s offices. (Currently, that distinction belonged to Eylea, which totaled just under $3 billion in expenditures in 2019.)

Even though the evidence the drug works is far from convincing, and it carries a significant risk of side effects like brain swelling and bleeding, geriatricians expect many families to jump at the chance for a new treatment. Because right now, the handful of drugs in the space show, at best, marginal benefits in slowing Alzheimer’s march.

A neurologist recently recounted what is likely to become a typical scene in clinics around the country. “I presented the data to the patient and her husband, and they didn’t hear a word I said about my concerns,” he told The New York Times. “All they heard was there might be benefit.”

It remains to be seen whether patients will profit from the new drug. But for Biogen, the verdict is already in. The day the FDA announced its decision, the company’s stock soared 38%.

–

Adam Cohen is OMRF’s senior vice president & general counsel and interim president. He can be reached at contact@omrf.org. Get On Your Health delivered to your inbox each Sunday — sign up here.