Dr. Gabriel Pardo spent years finding his true path – solving the mysteries of multiple sclerosis

By the time Dr. Gabriel Pardo turned 30, he’d devoted nearly half his life to becoming, and being, a physician. He had a thriving practice as an ophthalmologist. He was a vice dean at a prestigious medical school. He’d also been handpicked to start a new academic division at that same medical school.

He was, by all appearances, riding high.

Still, things are not always as they seem.

In his practice, he’d begun seeing cases that went beyond what he’d encountered in textbooks. Or his medical training. Patients came in with inflammation of the optic nerve that was causing more severe damage than Pardo expected. Others presented with eye movements in patterns that defied conventional wisdom; whatever root cause Pardo could identify failed to explain what his patients were experiencing.

These were people living with head-scratching conditions that involved the eyes – but that had roots in the neurological system, a vast and complex network that involved the brain and brain stem. The patients often faced painful and debilitating symptoms, and they came to Pardo seeking help.

Too often, the young physician had none to offer.

It was, Pardo says, “humbling” to realize there was a gap between the skills he’d believed he had and those he actually possessed. “You think you’re good at this, and then, all of a sudden, you realize you’re not as good as you thought.”

It would have been easy to ignore. Just refer the tough cases to a neurologist. On to the next patient with cataracts.

But Pardo chose another path. He applied for and received a fellowship to study those complex neuro-ophthalmological disorders. That fellowship would force him to put his career on hold for two years; it would also take him to a new country and a new continent. And even though he’d leave with plans to return and resume his practice, that would not happen.

Instead, he’d devote his career to treating patients with multiple sclerosis, a condition that, at this point, he’d never encountered in his practice. He’d do it thousands of miles from where he’d spent nearly his entire life, as the founding director of OMRF’s Multiple Sclerosis Center of Excellence.

Pardo’s journey would prove to be long. Unpredictable. Rewarding. And one that he would not change one bit.

But to understand how he got here, and how he became the physician-researcher he is today, you can’t start in the middle. Like all good stories, you have to go back to the beginning.

Medicine did not run in Pardo’s family. The son of an economist, he was born in Lincoln, Nebraska, where his father was attending a summer course while earning his master’s degree. Once the elder Pardo completed his coursework in the U.S., he and his family returned to their home in Bogotá, Colombia, where Gabriel would grow up.

In Bogotá, Gabriel attended a preparatory school run by an order of Benedictine monks from, of all places, North Dakota. The English the monks taught him would, it turns out, come in quite handy later in his life.

The monks’ philosophy of education – encapsulated by the school’s motto, which translates to English as “to work and to pray” – would likewise play a central role in shaping Pardo’s future. “They imparted this idea of taking a disciplined approach to learning,” says Pardo, “and that education represented the path to a good life.” Those principles resonated with Pardo, who found himself particularly drawn to classes in the biological sciences.

In Colombia, students go straight from high school to professional school. So, at 17, Pardo was forced to choose his career path. He opted for one that seemed like the most natural extension of the biology classes he enjoyed: medicine.

Medical school in Colombia lasts longer than in the U.S., so Pardo spent the next six years earning his medical degree. A year of mandatory medical service to underserved patient populations came next, followed by a three-year residency in ophthalmology. After three years of private practice – alongside a pair of academic appointments – Pardo embarked on his neuro-ophthalmology fellowship at the University of Texas, Galveston. It was there that he encountered his first patients with multiple sclerosis.

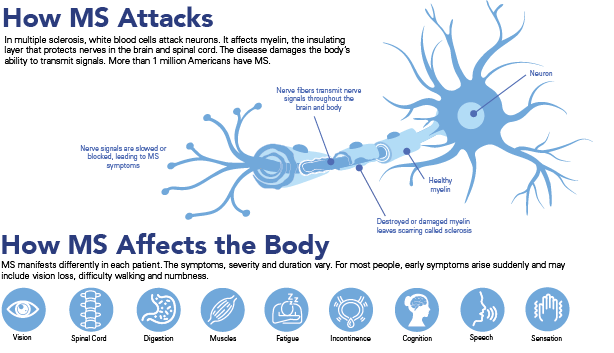

For reasons scientists don’t yet fully understand, in MS, the body’s immune system becomes confused. As a result, its white blood cells attack its own neurons. Those assaults eventually begin to destroy myelin, which insulates nerves in the brain and spinal cord. Over time, that loss of protection leads to a host of problems.

For most of the estimated 1 million Americans living with MS, early symptoms arise without warning. Frequently, they include vision loss, difficulty walking and numbness. The disease has no known cure, and its damage accumulates. Because symptoms are different in each person, and because they can cycle in periods of flares and remissions, MS can go undiagnosed for long periods of time, sometimes years.

Three decades later, Pardo still recalls seeing those initial MS patients in Galveston. The experience felt, he says, as if someone had switched on a light. “It was like” – his eyes widen, and his lips part as he searches for words. But, after a few moments of finding none, he simply opens his hands and draws them away from his body, then makes a popping sound.

“It was like” – searching again for the words, this time finding them – “an epiphany.” He knew what he wanted to do with his life. He’d devote himself to unraveling the secrets of this debilitating disease. To caring for those who live with it.

Intellectually, MS combined several different elements that appealed to the young physician. There was ophthalmology, the eyes that he’d already spent so much time studying and treating. There was neurology, the brain and nervous system whose secrets he’d only begun to plumb. And there was immunology, a field that was largely new to him but that held considerable intrigue.

That emptiness he’d felt in Bogotá, when he’d understood how much he didn’t know, this could fill that. It would be a challenge, he knew. Not only would he have to master a whole new body of knowledge, but he’d have to stay in the U.S. to do so. Because, for whatever reason, that was where the people living with MS were. And he couldn’t help them from thousands of miles away.

Pardo returned to Colombia to close his ophthalmology practice. To treat patients in the U.S., he’d have to complete yet another round of neurology training: a year of internship followed by three years of residency. In total, that would mean nearly 20 years of preparation to reach the destination that, until recently, he hadn’t even known he was headed for.

Still, Pardo says the decision to invest another four years of his life to get there wasn’t as hard as one might imagine. “This was what was going to fulfill me. This was what was going to make me happy.” He applied for and was accepted for a neurology internship and residency at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center.

PARDO WAS HUMBLED WHEN HE REALIZED THERE WAS A GAP BETWEEN THE HEALING SKILLS HE BELIEVED HE HAD AND THOSE HE ACTUALLY POSSESSED.

Although English was not his native language, the monks from North Dakota had taught him well. Plus, Pardo’s fellowship in Galveston had taken his conversational skills to a new level. By the time he reached Oklahoma City, he had his second language down. More or less.

“I would ask patients about their livers,” he says, laughing at the memory. “But it would come out LEE-ver.”

Throughout his training at OU, Pardo made it known that he wanted to establish a practice specializing in the treatment of MS. He made his initial foray at OU, where the chair of the department of neurology recruited him to start a neuro-immunology section once he completed his residency. Pardo would eventually leave OU for private practice, but not before he got a taste of research at OMRF.

Beginning in the 1980s, OMRF built a research concentration in lupus. In the ensuing decades, those efforts grew to include other illnesses such as rheumatoid arthritis and Sjögren’s disease. The conditions, grouped under the umbrella of autoimmune diseases, share a common mechanism: They’re triggered when the body grows confused and tries to destroy its own cells.

Dr. Judith James, who trained with Pardo at OU and now serves as OMRF’s executive vice president and chief medical officer, remembers that the two shared a fascination with autoimmune diseases. “He came to the lab at OMRF in his free time to study them,” remembers James.

Pardo first grew intrigued with the role that genetics play in autoimmune illnesses. Then, working with a senior scientist at the foundation, he obtained federal grant funding to examine whether a common communicable illness – Epstein-Barr virus, which causes colds in most people and mononucleosis in some – might serve as a trigger for MS.

Traditionally, scientists and physicians had viewed multiple sclerosis as a degenerative neurological condition, grouping it alongside Parkinson’s and Lou Gehrig’s disease. But as they developed a deeper knowledge of MS, they also pinpointed an immunological component: The disease process seemed driven by the body’s misguided assaults on the myelin that sheaths nerve cells.

MS joined the list of autoimmune diseases, which, taken together, are now believed to affect an estimated 1 in 10 individuals. In the U.S., that means that approximately 30 million people live with autoimmune illnesses.

Pardo’s research project on MS was long and involved, modeled on similar studies foundation scientists had done linking Epstein-Barr to lupus. When he moved to private practice, he was unable to continue the work. While he knew he wanted one day to circle back to research, he just wasn’t sure how – or if – that might happen.

Pardo’s research project on MS was long and involved, modeled on similar studies foundation scientists had done linking Epstein-Barr to lupus. When he moved to private practice, he was unable to continue the work. While he knew he wanted one day to circle back to research, he just wasn’t sure how – or if – that might happen.

Over the next decade, Pardo built the sort of medical practice he’d envisioned in Oklahoma, one focused on treating MS. But because nothing similar had ever existed in the state, it took him several years of running a more general neurology practice before he had enough MS patients to allow him to pivot and devote his time exclusively to them.

In the interim, he received an offer for a faculty position at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, where he could have joined an established practice centered on MS. But, Pardo says, the move just didn’t feel right.

“I already had a taste of the needs here,” he says. “I wanted to provide to the community of MS patients in Oklahoma.”

For Pardo, clinical trials would represent a key part of serving that community of MS patients. Through this mechanism, people living with the disease can obtain early access to investigational drugs not yet available on the market. Also, the study sponsors provide the treatments free of charge. “That means patients typically don’t have any out-of-pocket expenses,” says Pardo.

In exchange, the patients agree to participate in detailed studies that examine the drugs’ efficacy and safety. And it’s these studies that ultimately determine whether the therapies receive approval from the Food and Drug Administration for widespread use in hospitals and clinics.

As Pardo’s reputation spread, he attracted more trials. This brought new drugs to Oklahoma patients, at a time when the treatment landscape for MS was improving dramatically. He could provide patients with novel, life-changing and free medications, often years before they’d reach the market.

It was, Pardo says, “incredibly rewarding to see the community flock toward this specialized center.” He’d dared to take a step back to understand a complex disease that had once seemed beyond his comprehension. In the process, he’d established himself as a national pacemaker in administering clinical trials for MS. He now had a large and stable patient base, and he used the knowledge and expertise he’d developed to help them lead their best lives.

In short, Pardo now had the career he’d once only imagined. Until, one day, he allowed himself to dream bigger.

As awareness of autoimmune diseases grew, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases sharpened its focus on the conditions, creating a centers of excellence program for research on the illnesses. In 2009, the institute named OMRF as an inaugural Autoimmunity Center of Excellence, one of only a handful around the country. With the designation came significant federal funding. But if OMRF wanted to remain a member of this exclusive club, which included major academic medical centers like Harvard and Duke, it could not stand pat.

“We were a relatively new Autoimmunity Center of Excellence, and they were encouraging us to be multi-disciplinary,” says James. OMRF, she thought, could use its existing base of rheumatological care and biological samples gathered from patients as a beachhead for expanding clinical research. “It seemed this was the perfect time to start a Multiple Sclerosis Center of Excellence at OMRF,” she says.

She and Dr. Steve Prescott, then OMRF’s president, recognized they needed someone with a unique skillset to lead the new center. In a world where the practice of medicine was increasingly driven by the bottom line – number of patients seen each day, billings, collections – they wanted someone cut from a different cloth: a physician with the ability to marry compassionate care and research.

“My first thought,” says James, “was to reach out to Dr. Pardo to see if we could entice him back to OMRF.”

Pardo understood the hurdles that would come with moving his practice to the foundation. But with the MS Center, he saw the opportunity to build something altogether different – and better – at OMRF.

“The vision was to offer comprehensive, multi-disciplinary care that puts the patient first,” he says. “At the same time, we’d be able to contribute to the development of clinical studies and basic research.”

In 2011, OMRF completed construction of a new research tower, the largest campus expansion in the foundation’s history. At the heart of that space was the new Multiple Sclerosis Center of Excellence. Pardo would serve as its founding director.

In the nearly 14 years since, Pardo and his team have developed a center at OMRF that he describes as “a unicorn.” The term, he knows, is overused, but when comparing it to his colleagues’ medical practices around the country, he says it’s apt.

“We have the autonomy to provide care to patients in the way we think is best and not be restricted by the way healthcare is being practiced today,” he says. If he or his fellow caregivers need to spend 45 minutes or even an hour with a patient, they can do that. Nor do they allow insurance coverage to govern treatment decisions. Quite simply, he says, “We have the freedom to provide the care that each patient needs and deserves.”

That approach has helped build a practice that now serves more than 4,000 patients each year. They come to OMRF from every corner of Oklahoma as well as neighboring states. And almost as soon as they arrive, they can see the ways in which the Center’s approach to care is far from typical.

For Kelsey D’Emilio, who began receiving care for MS at OMRF in 2016, the difference was evident even at her initial visit with Pardo. “From day one, it wasn’t about treating my symptoms,” she says. “It was about the hope for a cure.” She’d undergone treatment at several other sites previously and even participated in clinical trials of new medications. Yet those drugs had proven ineffectual and brought punishing side effects. On top of that, D’Emilio says the physicians running the trials treated her “like a test dummy.”

At OMRF, Pardo encouraged her to participate in a clinical trial of a different medication. D’Emilio was reluctant, worried not only about how the drugs might make her feel but about once again being treated as an object of academic interest rather than a person living with disease.

However, she quickly came to understand that Pardo was not like her previous caregivers. “He was the first doctor who explained the science behind the medication,” she says. He gave her an overview of the research scientists were doing at OMRF. “I felt the entire MS Center of Excellence was part of my team to overcome this disease.”

D’Emilio appreciated the patient-centered approach Pardo and his team employed. “Trying to treat my MS used to be a full-time job,” she says. “But once I came to OMRF, what had taken six months now took one day.” Instead of a patchwork of different sites for labs, infusions and appointments with specialists, everything happened in the same facility.

“They make each aspect of the experience easier for you,” says D’Emilio. That approach holds true, she says, down to one telling detail. “They always know me by name.”

D’Emilio decided to participate in the trial. Within six months, lesions on her brain and spinal cord were under control. Feeling returned to her body where it had been lost. Her vision improved, and she could walk normally again. “I got my life back,” she says.

Almost a decade later, she remains under Pardo’s care. In that time, he’s helped control a disease that once controlled her, enabling her to live as she never dreamed possible. That life is not without challenges, but it has allowed D’Emilio and her husband, Gerard, to expand their family: Luca was born in 2023, and his sister was due at the time of publication.

a daughter.

Not long ago, D’Emilio sat down with her father, who expressed sadness that his daughter still had to live with the burdens of MS. “We all prayed for a miracle,” he told her. “I just wish you could have gotten it.” His daughter, though, saw things differently.

“Dad,” she told him, “you got the miracle you wished for.” She had, indeed, found an existence that was as close to a cure as she had ever known; it just hadn’t arrived in the way her father had envisioned. “Sometimes,” she reminded him, “miracles come in the form of scientific advancements.”

For MS care, says Pardo, those scientific advancements have proven “transformational.”

When he first began practicing more than three decades ago, not a single drug existed that was approved for treating MS. Since then, the FDA has green-lit more than 20 new MS medications, and another half-dozen promising investigational treatments are in the final phases of clinical trials. Other than the first few early drugs, Pardo has been involved in the trials for each, with the vast majority of those taking place at OMRF’s MS Center. “We’ve been participants in making history for MS,” he says.

“MY APPROACH TO EVERYTHING IS THAT YOU PUT IN AN HONEST DAY’S WORK. That, AND I TRY TO DO EVERY DAY

WHAT MY MOTHER TAUGHT ME AS A CHILD: BE KIND.”

The new generation of medications, says Pardo, represents a major step forward. “They’re highly effective. We’ve gotten better and better at addressing patients’ problems.” The drugs, he says, are particularly good at shutting down the acute inflammatory phases of the disease. “We came up with treatments for those because that’s what was evident to us as scientists and physicians.”

However, even as doctors have been able to use the latest therapies to “put that fire out,” says Pardo, they’ve come to recognize that patients continue to worsen. “It’s the humbleness of science,” he says, an acknowledgment that there’s always more to learn. Researchers have discovered a second mechanism driving MS progression, one the current line of medications cannot counter. “There’s an underlying smoldering inflammatory activity that’s taking a slower, more profound toll on patients’ cognitive and physical function.”

The next step, he says, is to identify strategies to shut down that inflammation.

Beyond that, Pardo and his fellow MS researchers are also looking to other scientific frontiers. “What can we do to improve function in people who’ve already experienced damage? Can we repair myelin and nerve cells?” And, ultimately, “Can we prevent this disease?”

That final issue, prevention, comes with a personal coda for Pardo. A few years ago, two scientific studies came out showing that – as with lupus – Epstein-Barr virus seems to serve as a trigger for the autoimmune response that leads to MS. That finding answered the question Pardo was investigating more than two decades ago at OMRF, during his neurology residency.

Because the virus starts the process resulting in MS, Pardo and others are now asking another question: “What would happen if we developed a vaccine against Epstein-Barr?”

To that end, a clinical trial for a new Epstein-Barr vaccine is now in the works. Pardo plans to bring that trial to OMRF, where his patients will once again have access to a clinical intervention that could prove to be a game changer.

The idea behind the trial echoes that of another vaccine – shingles. There, following an initial infection in childhood, stores of the chicken pox virus continue to lurk in the body. When those stores are awakened later in life, the result is shingles, a painful and debilitating illness.

Like that virus, says Pardo, the Epstein-Barr virus “takes residence in our body and never leaves.” With the vaccine trial, Pardo and colleagues will see if the shot can rid the body of stores of the virus still present in its cells. Scientists, he says, hypothesize that “the continued presence of the virus in the body is what induces new autoimmune activity down the road.” If that’s the case, “then eliminating the virus might reduce the risk of new autoimmune attacks.”

A vaccine that could blunt, or even halt, the progression of MS? It’s tantalizing to imagine. Still, it might not prove out. But if it does, Pardo’s patients will be among the very first people to benefit.

Moving forward, Pardo is excited about a pair of projects currently on the horizon at OMRF. One is the addition of a human performance lab, where he and his team will work with patients to develop ways to more accurately gauge the progression of MS. OMRF will also build a new center for human imaging, which will house a new research-grade magnetic resonance imager, a powerful tool to aid in both patient care and developing a deeper understanding of MS.

Both represent key undertakings for OMRF, which has secured a major gift to help establish the human performance lab. Meanwhile, the foundation is in the midst of a fundraising campaign for the human imaging center. (For more details, see page 8.)

Pardo understands the crucial role that philanthropic support plays for the MS Center. “Donors created this one-of-a-kind resource in Oklahoma. As we launch these new projects, their help will not only accelerate our research, but it will also impact the lives of people living with MS,” he says.

When he thinks about what the MS Center has become and where it’s headed, he doesn’t think about 5- or 10-year plans. Instead, his thoughts return to his upbringing in Bogotá. To the lessons he learned from the monks from North Dakota.

“My approach to pretty much everything is that you put in an honest day’s work,” he says. “That will get you where you need to be.” Oh, and there’s one more thing. “I just try to do every day what my mother taught me as a child: Be kind.”

He looks up from his desk. It’s a little after 6:00 in the evening. He’s finished a full day in the clinic, but he still has a stack of charts to work on. That’s okay, he says. Taking care of people living with MS helps keep things in perspective.

He gestures upward, to a trio of small bronze figures mounted on his wall. They’re each clutching a rope and pulling upward, straining.

“These climbers remind me of my patients,” he says. “Of their daily struggles.”

His road to this place, to this moment, has been a long one. It hasn’t been straight. Or easy. But, he says, it’s brought him to exactly where he needs to be.

“I try to make a difference today and tomorrow for people living with an extremely challenging disease.” To help them, he says, brings tremendous satisfaction. But sometimes the problems his patients face are beyond his ability to remedy.

For those, he’ll keep searching for answers.

–

Read more from the Winter/Spring 2025 edition of Findings

President’s Letter: The Life-Changing Impact of Clinical Research

Family Legacy

Voices

Ask Dr. James

Three-Peat

Meeting the Challenge

A Biologist From Birth

On a Mission

Coming to America