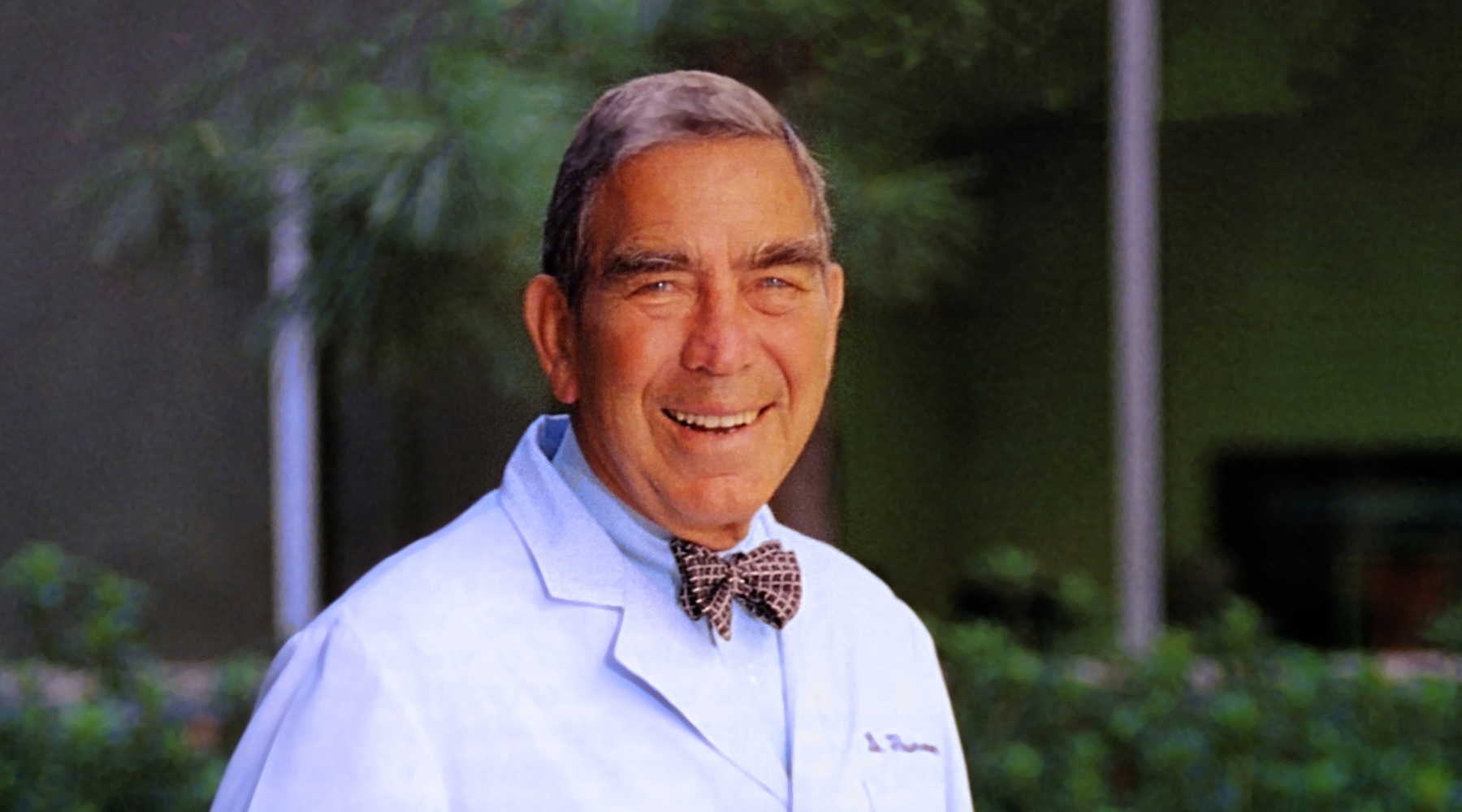

When Dr. William Thurman joined OMRF as the foundation’s seventh president in 1979, he brought the lab coat he’d worn since his days training as a pediatric oncologist. That powder-blue garment, along with the bow ties he favored, would become synonymous with OMRF. And while memorable, Thurman’s sartorial flourishes would prove to be the least of his many legacies at OMRF.

He immediately set to work building the foundation’s scientific programs. His first focus was cancer research, a rapidly emerging field in which OMRF’s presence had diminshed. Making use of an extensive Rolodex developed while chairing the pediatrics departments at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center and the University of Virginia, serving on the faculty at three other institutions, and a stint as provost at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Thurman successfully recruited several nationally prominent cancer researchers to OMRF.

Dr. Paul Kincade, who then ran a thriving cancer research laboratory at Memorial Sloan-Kettering, was one of Thurman’s first targets. “After a single visit to OMRF and Dr. Thurman, my lab staff was ready to leave New York and move to Oklahoma. And that’s what we did,” says Kincade, who would go on to spend more than three decades as a scientist at OMRF.

Thurman’s bushy eyebrows, deep voice and soft, Southern accent—along with the bedside manner of a seasoned physician—bespoke trust. That impression, says Kincade, was spot-on. “He told me he could provide for my needs in the lab, and he was true to his word. He really took care of his people.”

Although trained as a physician, not a laboratory scientist, Thurman had a keen eye for talent and trends in research. Sensing that immunology and autoimmune diseases were another area of increasing need, he recruited Dr. Morris Reichlin from the State University of New York at Buffalo to start a new research program in 1981. Today, that program, now known as the Arthritis and Clinical Immunology Research Program, is one of the nation’s leaders in the field, earning recognition from the National Institutes of Health as one of only 10 Autoimmunity Centers of Excellence. It employs more than 150 OMRF staff members, who study diseases that include lupus, rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis.

Thurman’s ability to identify and foster scientific talent paid similar dividends in cardiovascular biology, where he brought in Drs. Charles Esmon, Fletcher Taylor and Rod McEver. Each would go on to make watershed contributions to the field, and their discoveries have led to lifesaving drugs—and another is poised to reach hospitals and clinics in the coming years.

Thurman’s ability to cultivate research success was no accident, says Kincade. “With Bill at the helm, we always had complete independence and the resources we needed to succeed.”

As OMRF’s research thrived under Thurman, the foundation expanded markedly. During his 18 years as president, the foundation’s budget quadrupled, and it added hundreds of thousands of square feet of laboratory space with a trio of new research buildings.

“I think one of the things I’ve liked best about this job has been the opportunity to see OMRF grow from relative infancy to become a mature center of research excellence,” Thurman told The Oklahoman upon his retirement in 1997. “It’s also been a real pleasure to see research translated from our laboratories and become actual treatments for human disease.”

Following his retirement, Thurman and his wife, Gabrielle, moved to the Seattle area. Still, they remained involved in the Oklahoma City community, staying in close touch with many friends (a group that included a multitude of present and former OMRF scientists). They also continued their long-time work with the Children’s Center in Bethany.

In February, Thurman died at the age of 89. He is survived by Gabrielle, three daughters, eight grandchildren and a research foundation where his contributions live on.