Feb. 22, 1948 – May 28, 2021

Dr. Stephen Prescott came to OMRF with impeccable credentials. A physician-researcher, he’d enjoyed a stellar career in the laboratory before pivoting to administration, where he’d led a prestigious cancer institute. There was, says OMRF Board Chair Len Cason, only one slight blemish on his resume: “He was a Texan.”

Still, when it came time to interview candidates to become OMRF’s president, even Prescott’s Lone Star lineage couldn’t hold him back. “Steve said, ‘Why don’t you run through your list and talk to me after you’ve identified your lead candidates,’” remembers Cason. “And I said, ‘Steve, I have a list of candidates, but, honestly, I don’t have a runner-up to you.’”

Prescott knew OMRF through Dr. Rod McEver, now OMRF’s vice president of research, with whom he shared his first research fellowship in the 1970s and continued to collaborate scientifically throughout his career. Prescott also served as an external scientific advisor to OMRF. “He was very impressed with everybody,” recalls his wife, Susan. “The more people he met, the more convinced he became that OMRF was the right place.”

Prescott knew OMRF through Dr. Rod McEver, now OMRF’s vice president of research, with whom he shared his first research fellowship in the 1970s and continued to collaborate scientifically throughout his career. Prescott also served as an external scientific advisor to OMRF. “He was very impressed with everybody,” recalls his wife, Susan. “The more people he met, the more convinced he became that OMRF was the right place.”

When Cason offered him the job, Prescott didn’t hesitate. “He interviewed in other places, but Oklahoma felt so familiar,” says Susan. “It was like coming home.”

Growing up, home had been College Station, Texas. Although Prescott’s father was a biochemistry professor, science wasn’t his first love. “I spent way too much of my life dreaming of being a major league baseball player,” he remembered in an interview with Findings.

When college curveballs put an end to that fantasy during his freshman year at Texas A&M University, the one-time outfielder decided to redirect his energy into pre-med classes. After an honors degree at A&M, he headed to the Baylor College of Medicine, where he also graduated with honors. A residency in internal medicine at the University of Utah and a post-doctoral fellowship at Washington University in St. Louis followed.

It was in St. Louis that Dr. Prescott cut his teeth as a medical researcher. “I’m innately curious, and I like to understand how things work,” he said. “So, I knew I wanted to have a career in research.”

Prescott joined the faculty at the University of Utah, where he enjoyed an eminent career in the lab. The underlying theme of his research was understanding how blood vessels behave. The field didn’t have

a name when Prescott began his research career, but by the early 1990s, scientists had coined the term “vascular biology” to describe this emerging discipline.

The work had implications for heart disease, but it also touched a number of different areas. His research led to the development of Cox-2 inhibitors, the anti-inflammatory drugs now used to treat severe arthritis. And it led him into cancer research, searching for new ways to stop tumor growth. Appointments as the senior director for research and, ultimately, executive director of the university’s Huntsman Cancer Institute followed.

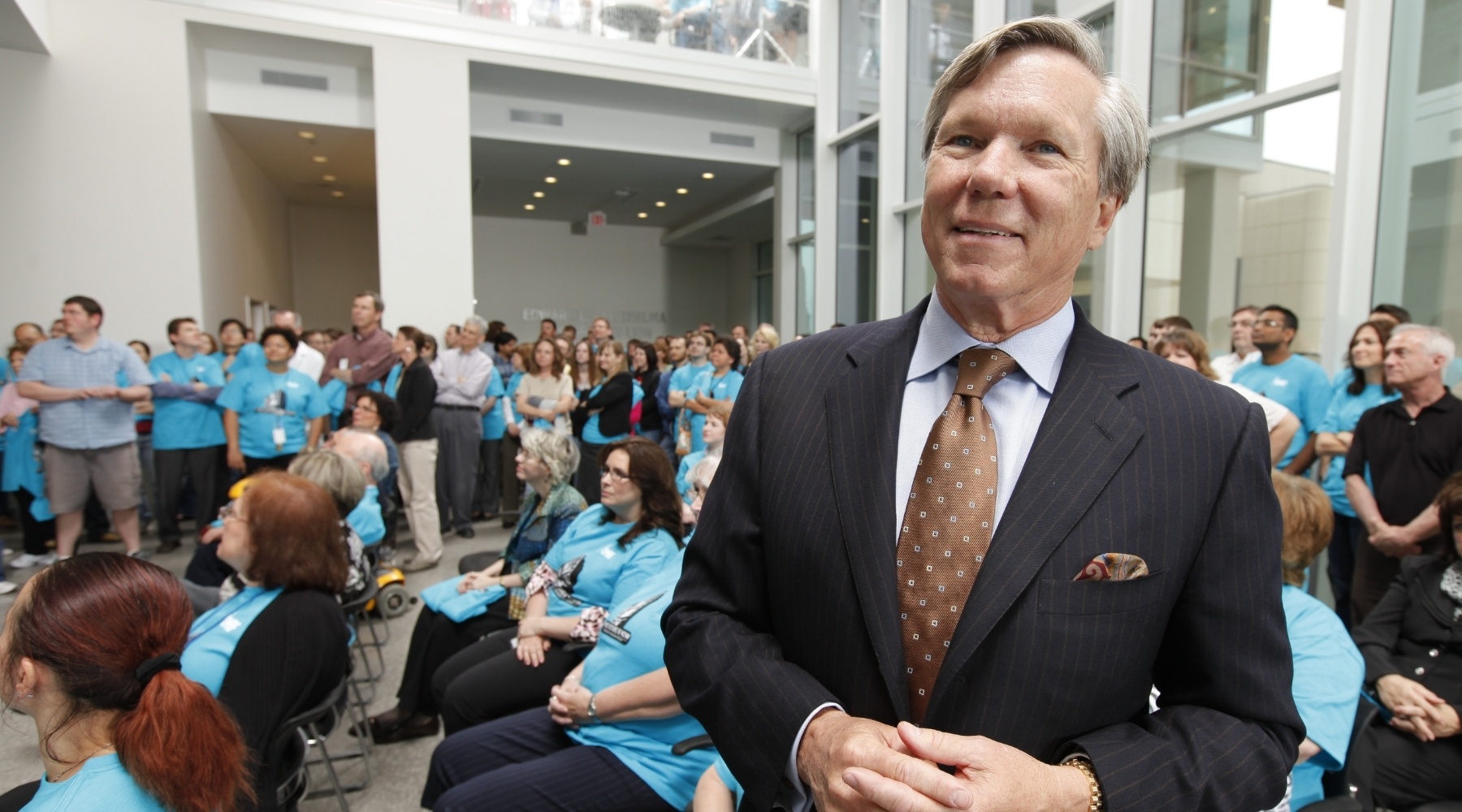

Prescott became OMRF’s fifth full-time president in 2006. Over the next decade and a half, he took the foundation to new heights. He orchestrated the largest campus expansion in OMRF history, raising $100 million to construct a new research tower. It houses the state’s only comprehensive multiple sclerosis treatment center and a variety of state-of-the-art labs, including one that bears Prescott’s name, thanks to the generosity of the Puterbaugh Foundation.

During his time at the helm, Prescott recruited more than 40 new principal investigators to the foundation, and three drugs and a diagnostic test born in OMRF labs reached the market. The Foundation also repeatedly earned top marks from Charity Navigator, the nation’s leading nonprofit evaluator, and in rankings of Oklahoma’s top workplaces.

As with his research – 270 articles cited nearly 40,000 times – his leadership earned him numerous plaudits. Among those honors were Oklahoma’s Most Admired CEO, the Hall of Fame Leadership Award from the OK Bioscience Association, and, finally, induction into the Oklahoma Hall of Fame. Not bad, Prescott would have joked, for a recovered Texan.

“He led us to another level,” says McEver. “Under Steve, OMRF has unquestionably increased its stature and recognition among scientists across the world.”

In April, Prescott announced his retirement. “I’ve been lucky enough to help guide this wonderful institution for 15 years,” he said. “And nothing makes me happier than knowing the scientists of OMRF will continue the tradition of biomedical research excellence long after I’ve gone.” OMRF’s board named longtime Senior Vice President and General Counsel Adam Cohen interim president, and the board is now leading a search for Prescott’s permanent successor.

Since being diagnosed with urothelial cancer in 2017, Prescott had been open about his struggles with the disease. While the treatments proved debilitating at times, he showed remarkable resiliency and positivity in the face of odds that grew increasingly long. When his therapeutic regimen necessitated a portable chemotherapy pump, Prescott simply stuck the device in a backpack that he wore to the office, board meetings and even the many outward-facing events his position at OMRF demanded. “Not once did I hear him say, ‘Why me?’ or feel sorry for himself,” says Cason.

Prescott acknowledged that his cancer journey gave him a fresh appreciation for research. “It’s driven home why it’s so important to keep searching for new approaches to treat disease,” he wrote in 2019. But, he said, the most “wonderful” part of having cancer was the support that so many people showed to him and his family.

During the final year of his life, even as his health plummeted, Prescott added a new role: Covid-19 educator. He spent countless hours working with television stations, newspapers and other audiences, teaching the public about the novel coronavirus. His goal, he often said, was to distill scientific fact from fiction. “He was Oklahoma’s Dr. Fauci when we all needed someone we could trust,” says Scott Meacham, president and CEO of i2E. “He was the calm voice of reason.”

Prescott is survived by Susan, his wife of 52 years; his brother, Don; his children, John and Allison; and his granddaughters, Ruby, Lily and Isabella (all three of whom he liked to describe as “perfect”). “Steve can never be replaced,” says Meacham, speaking for himself and countless others, “only cherished for what he left behind.” – AC