The Presbyterian Health Foundation Nurtures Oklahoma Biomedical Research Progress

Tom Gray and Rick McCune aren’t scientists. But as chairman of the board and president, respectively, of Oklahoma City’s Presbyterian Health Foundation, the pair shares a goal with OMRF’s researchers: to improve the health of all Oklahomans.

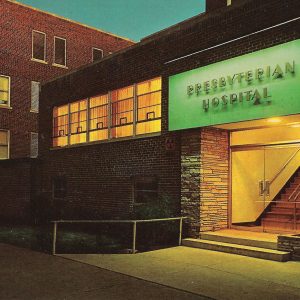

PHF was founded in 1985 following the sale of Oklahoma City’s Presbyterian Hospital, then the largest hospital in the state. With the invested proceeds from that original transaction and, later, the sale of the PHF University Research Park, the foundation has awarded more than $215 million to Oklahoma organizations aligned with the foundation’s mission.

While there are several hundred entities like PHF, as far as Gray and McCune know, the foundation is unique among them in dedicating the lion’s share of its budget to one thing: accelerating biomedical research. And every one of those dollars is awarded to research institutions on Oklahoma City’s Health Center campus.

“We want to keep growing Oklahoma as a center of research excellence,” says Gray. “You do that through disciplined investments and funding.”

Throughout the year, the foundation gives grants that support needs and programs at OMRF and the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center. Those awards include seed funding for new ideas, an M.D./Ph.D. training program, equipment, scientist recruitment and retention, and collaborative grants, which enables teams to work across disciplines.

Along with Gray and McCune, a staff of three oversees day-to-day administration and finances. The team relies on PHF’s scientific advisory committee, made up of experienced local researchers, to evaluate grant applications and make funding recommendations to its 13-member board of directors.

At OMRF, two of the most utilized awards are for equipment and seed funding, says Vice President of Research Dr. Courtney Griffin.

In Oklahoma City, there was only one Presbyterian Hospital. But it was part of a long tradition of hospitals in major metropolitan areas – Charlotte, Dallas, Denver, Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, to name a few – that bore the “Presbyterian” moniker. Although the hospitals were not formally affiliated, like many healthcare facilities, they all started as sectarian institutions. And as their names suggest, each of them had a mission that was in some way tied to that particular branch of Protestantism. For example, at New York’s Presbyterian Hospital, in addition to medical care, Harper’s Weekly in 1872 wrote that patients received “the ministrations of the Gospel agreeably to the doctrine and form of the Presbyterian Church.” Although the hospital doors were open to all, The New York Times reported that many patients claimed to be Presbyterians – just in case.

Unlike seed grants that support one or two labs, equipment grants can benefit an entire research program. And while funding for high-powered microscopes and refrigerator-sized DNA sequencers may not grab many headlines, there’s a domino effect.

“You have to have great researchers to produce groundbreaking research,” McCune says. “To attract and retain great researchers, you have to have cutting-edge scientific equipment.”

Seed grants, on the other hand, fund proof-of-concept experiments or allow a scientist to develop a technology they need for a particular project. “That can be the difference between getting federal funding and not,” Griffin says. And she would know. When the National Institutes of Health awarded her a seven-year grant in 2019, it was thanks in part to PHF seed funding for developing two new research models. Without those models in hand, Griffin says, “almost no grant reviewer is going to be satisfied.”

In 2022, the NIH received more than 36,000 applications for its oldest and most commonly awarded grant mechanism and others equivalent to it, the R01. These multimillion-dollar grants provide several years of support for a scientist’s independent research program. Of those tens of thousands of applications, the NIH ultimately funds only a small fraction.

With the fierce competition for federal dollars, scientists need to demonstrate their ideas have a high likelihood of success to have the best shot at funding, says Griffin. “There just isn’t enough money to go around,” she says. “So, if the NIH is going to invest millions of taxpayer dollars in a scientist, they tend to tip the scales toward someone with a better chance of breakthroughs.”

OMRF scientists have a strong track record of winning this kind of funding. Currently, the foundation’s researchers have more than 50 active R01 or equivalent grants. Through its seed funding, PHF has played a role in securing scores of them, aiding in bringing tens of millions of federal dollars into the state of Oklahoma. In 2023, the NIH awarded one of those grants to OMRF cell biologist Dr. Susannah Rankin.

Rankin studies how our cells package chromosomes during cell division. When errors occur in the process, they can lead to issues ranging from miscarriages, genetic disorders, and birth defects to cancer. By understanding everything that must happen for cell division to go right, scientists can help prevent mistakes from happening in the first place.

In her application to the NIH, Rankin used preliminary data she’d generated through multiple PHF seed grants. “That kind of help to do those early steps – it can just change things,” she says. “It’s incredibly hard to get federal funding without early-stage results.” To her, PHF’s willingness to gamble on early-stage projects “is forward-thinking. Without high-risk, high-reward research, nothing would happen.”

For its part, PHF doesn’t fear projects that ultimately fall short of their goals, says April Stuart, PHF’s director of grants and programs. “Failure closes a door. If an experiment tells someone else where not to look, we see that as its own success.”

No matter the outcome, Gray says the potential payoff for Oklahomans and people everywhere is worth betting on. “When you plant a seed, either it’s going to produce, or it’s not.” But without seeds, he says, one thing is assured: Nothing will grow.

—

Read more from the Winter/Spring 2024 issue of Findings

Road Music

The X (and Y) Files

Voices: Meg Salyer

Ask Dr. James: Does a lifetime of radiation from medical imaging pose risks to patients?

Pain Killer

Living Legacy

Data Nerd