Can research from OMRF help women give birth later?

Menopause officially signals the end of female fertility. But for the majority of women, their ovaries begin to decline around the age of 35, many years before their menstrual cycles cease. This process can lead to a host of reproductive issues, ranging from difficulties conceiving to birth defects.

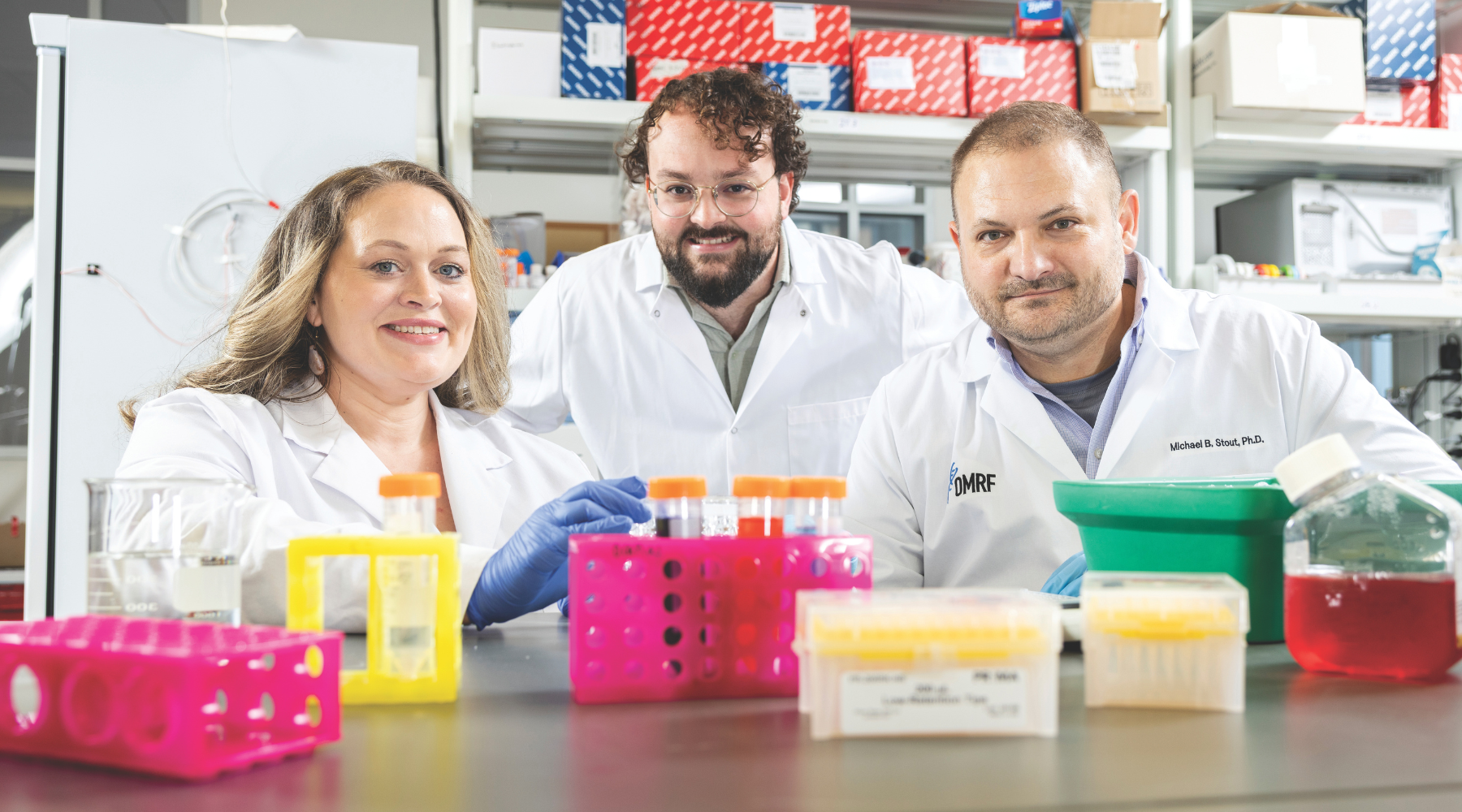

The driver of that reproductive downturn isn’t clear, but recent experiments conducted by OMRF scientists Drs. José Victor Isola, Sarah Ocañas and Michael Stout offer new clues. And with the upward trend in the age of pregnant women, the knowledge is critical. According to 2020 data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, nearly 19% of all pregnancies in the U.S. were in women ages 35 years and older.

Isola, Ocañas and Stout demonstrated for the first time that, in preclinical models that correspond to a woman in her mid- to late 30s, a particular type of immune cell accumulates more rapidly in the ovaries. “Now we can begin trying to understand why this is happening,” says Isola, a postdoctoral researcher in Stout’s lab. “Our findings represent a potential step toward trying to slow the ovarian aging process.”

Nearly 1 in 5 pregnancies are now in women ages 35 or older.

The experiments also showed that around the same time, inflammation forms in cells that encircle developing eggs. The inflammation complicates the process of an egg maturing to the point it can be ovulated and fertilized.

The scientists found a buildup of collagen in the normally pliable ovarian tissue, causing it to become fibrotic. “This is very important,” Ocañas says, “because when the tissue becomes hard and stiff, it makes ovulation of the egg much more difficult.”

“We still don’t know which came first,” Stout says. “Are those cells that encircle the egg drawing in all those immune cells, or are the immune cells causing the inflammation? That answer will require additional research.”

The journal Nature Aging recently published the team’s findings, which were made possible through funding support from the National Institutes of Health, Oklahoma City’s Presbyterian Health Foundation, and the Global Consortium for Reproductive Longevity and Equality.

Stout and Isola now plan to test whether inhibiting a specific protein complex reduces inflammation in the cells encircling the egg. “We’re still in the early stages of discovering why the ovary ages so fast and why it’s one of the first human organs to lose its function,” Isola says. “These experiments provided information that we can build upon.”

—

Read more from the Summer/Fall 2024 issue of Findings