In 1968, doctors gave Greg Kindell six weeks to live. He’s still here.

Like most organizations, OMRF maintains a general contact email address. It’s a place where people—and businesses and spammers—send their inquiries when they don’t know whom, exactly, at the foundation to ask.

A handful of new messages typically arrive each day. “You’ll see lots of vendors trying to sell things,” says Ryan Stewart, a public relations specialist at OMRF who helps monitor the account. “And there’s a steady stream of requests from patients.” Sometimes, they’re people trying to make appointments in one of OMRF’s clinics. “Or it can be someone suffering from a disease who’s read an OMRF press release about their condition.” Stewart does his best to separate wheat from chaff, referring earnest inquiries to the appropriate parties at OMRF—and ignoring junk.

One morning this past February, Stewart opened up the “Contact OMRF” mailbox and began scrolling through the messages. Amidst the LinkedIn requests to connect and canned sales pitches, he saw a subject line that caught his eye: “Cancer survivor story.”

The message came from a friend of a man named Greg Kindell. The email explained that at age 17, Kindell was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia, an aggressive form of leukemia. At the time—1968—this was essentially a death sentence.

Kindell was referred to the OMRF research hospital. The facility was a sort of final option for people suffering from deadly diseases, primarily cancers. There, OMRF physicians tried experimental treatments in a last-ditch effort to save patients’ lives.

Most of the time, it didn’t work.

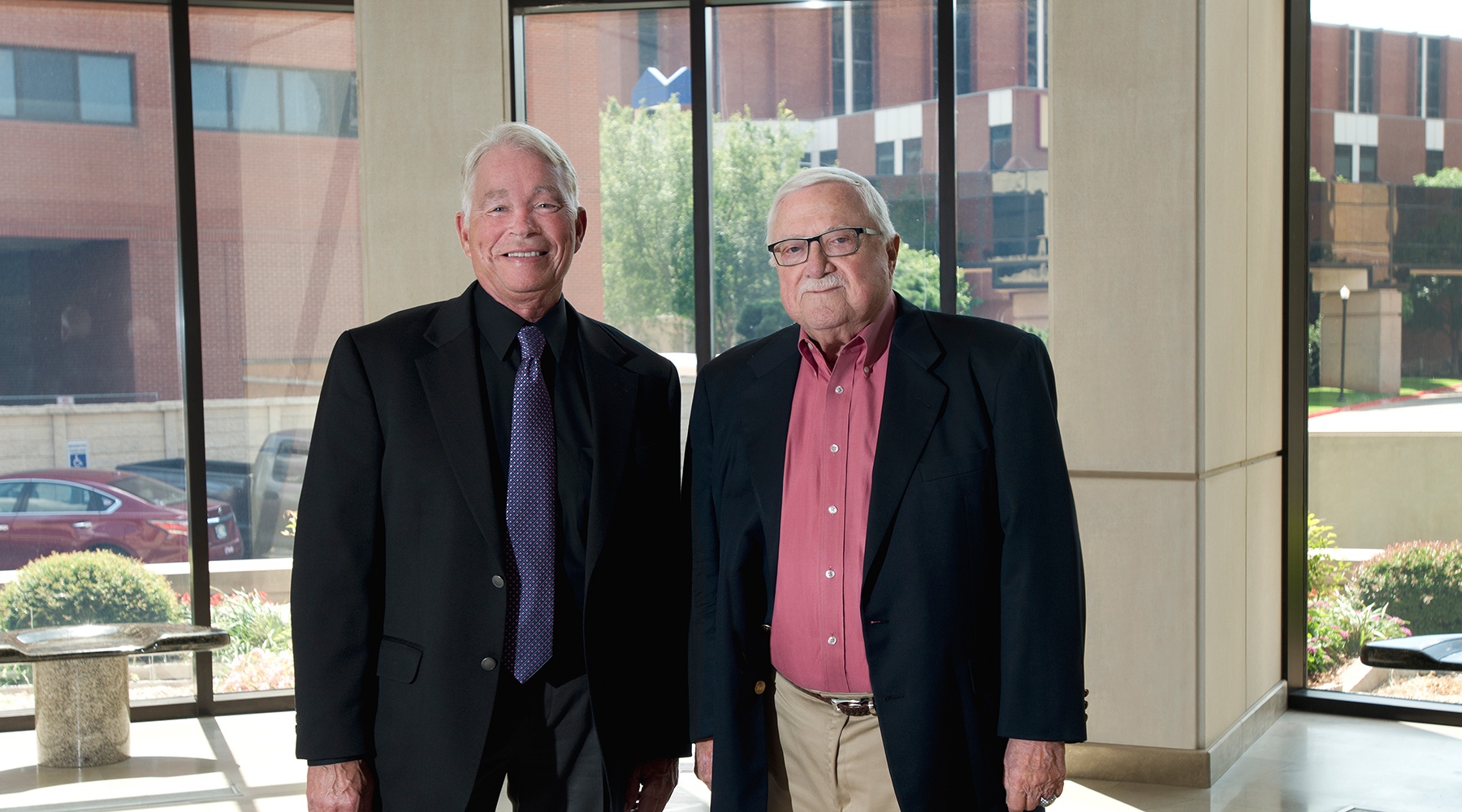

But, the email said, Kindell’s story was different. Now almost 67, he was preparing to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the moment his doctors at OMRF had declared him cancer-free. In the five decades since, the disease had not returned.

“I was wondering if you ever do a celebration story on survivors,” wrote Kindell’s friend. “Please let me know if you are interested, and I can put you in contact with him.”

OMRF opened its research hospital in 1951. Funded by private gifts and a pair of federal grants, the idea was to provide patients with cutting-edge therapies when all other treatment options had failed. “Our hospital provided the most advanced kind of translational research we had then,” says OMRF President Dr. Stephen Prescott.

The lion’s share of patients were children suffering from cancer, a disease that befuddled researchers and physicians alike. “Was it caused by a virus? Environmental changes? We had no intellectual framework for knowing what was really going on with cancer back then. It was all very vague, with many more questions than answers,” says Prescott, who was a cancer researcher and served as executive director of the University of Utah’s Huntsman Cancer Institute before coming to OMRF.

Blood cancers like leukemia proved particularly challenging. “The standard treatment for cancer was surgery to excise tumors,” says Prescott. “But in leukemia, there are no tumors to remove.”

In the spring of 1968, Greg Kindell was preparing for his junior track season at Pryor High School in northeast Oklahoma. Running up to 8 miles a day, the teen developed an infected toe. He also found himself more easily fatigued than usual. “I figured it was from running so much and wasn’t concerned,” he says. Eventually, the problems warranted a trip to his family physician, where the doctor prescribed a round of antibiotics.

Still, Greg grew weaker. When he experienced a prolonged bout of vomiting, his mother took him back to the doctor. There, he underwent blood work.

The results revealed sky-high levels of white cells, a signal that his body was fighting much more than a toe infection. At a hospital in Pryor, a subsequent test of his bone marrow confirmed what Greg’s physician feared: The 17-year-old was suffering from acute myeloid leukemia.

The most common form of cancer in children, AML floods the bone marrow and blood with abnormal white blood cells. These aberrant cells crowd out the normal white blood cells that act as the immune system’s primary defenders, leaving the body prone to infection and illness.

At the time, there was no treatment for AML. Greg’s physician told his mother the cancer was terminal. Your son has no more than six weeks to live, he said.

Still, the doctor offered one, faint ray of hope. In Oklahoma City, he knew OMRF was initiating a clinical study of people suffering from AML. Physicians at OMRF were seeking about 30 patients, all of whom would receive an experimental treatment for their leukemia.

The treatment, an aggressive form of chemotherapy, was unproven. But it was Greg’s only option. With his mother’s blessing, the doctor made arrangements to enroll Greg in the trial. After a hastily arranged family gathering—Greg didn’t realize it at the time, but it was his mother’s way of giving his relatives a chance to say good-bye to a young man they thought they’d never see again—mother and son made the 150-mile drive to OMRF.

Chemotherapy worked in 1968 the same way it does today. Doctors introduce powerful chemical agents to the bloodstream to kill off cancer cells. However, the chemicals are blunt instruments. Cells with naturally short lifespans that grow and turn over quickly, like those found in hair follicles and the lining of the mouth, die along with the cancer cells. Patients lose their hair, and many are plagued with painful sores in their mouths and elsewhere. Nausea, fatigue and fevers are commonplace.

The morning after beginning intravenous treatments at OMRF, Greg awoke to a wave of nausea that intensified as the day went on. The next round of chemotherapy left him vomiting uncontrollably.

“At that time, protocols were usually a combination of two or three different drugs,” says Dr. Richard Bottomley, who treated Greg at OMRF. In some patients, the drugs showed activity against AML. But physicians had no way of predicting who would respond—and who wouldn’t.

Treatment was further complicated by the fact that proper chemotherapy dosages were relatively unknown a half-century ago. How much was too much? How long should patients receive therapy? Over-suppression of bone marrow could leave patients anemic or dangerously immuno-compromised. As a result, some ultimately died from the very medicines doctors hoped would save their lives.

“OMRF’s hospital did a good job with what we knew at the time,” says Bottomley. “But patients often were extremely sick before they arrived here, so they started treatment at a disadvantage.”

That was the case with Greg. Desperate to beat back his leukemia, doctors continued his high-dosage chemotherapy in spite of the side effects.

Greg’s hair fell out. At times, his skin grew too painful to touch. Nurses had to devise soft slings out of sheets to turn and maneuver him in his hospital bed. Night sweats left Greg’s bedding and pajamas wringing wet, requiring changes three to four times a night.

The nausea persisted, and Greg’s weight plummeted, eventually dropping from 142 to 95 pounds. He grew more frail each day. The infected toe flared again and became septic. Weakened by the daily rounds of chemotherapy, he slipped in and out of consciousness. At the three-week mark, he recalls overhearing doctors tell his mother they were concerned he wouldn’t make it through the night.

Three months after he was admitted to OMRF’s hospital, his doctors declared Greg in remission. His cancer was under control, at least for the time being. He could go home, but his treatments would continue. Greg would travel to OMRF one week each month for booster treatments to keep his illness at bay.

He told none of his friends in Pryor why he was gone so often. He wanted to live a normal life and put leukemia behind him. Still, the disease cast a shadow over everything. For example, he says, dating was out of the question. “I didn’t want any girls to get too close to somebody who was probably going to die. It was easier that way.”

Greg stuck with his monthly week-long visits through high school. After graduation, his ongoing treatment schedule seemed to preclude college. “I was going to miss one week a month, so it was basically impossible.” Fortunately, his uncle, who was president of Murray State College in Tishomingo, understood Greg’s situation and offered a solution. “He told me that as long as I got my work in, they wouldn’t hold those absences for chemo against me.”

Whether it was the treatments or something else, the leukemia showed no signs of coming back. Over time, Greg felt healthier and grew more confident about his future. And, as might be expected of a young person, he eventually grew impatient with his once-monthly stays at the foundation.

“I wanted in and out on time,” he says. If there were any delays, he’d cause a stir. “I had things to do and wanted to be on the road as soon as I could.”

Maxine Watson supervised the nursing staff in OMRF’s research hospital and, even at a half-century’s remove, remembers Greg well. “Greg was a sweetheart. He was so positive about his life.” When he’d come for his booster treatments, she says, “He’d wait and wait for that last drip to come. As soon as it did, he’d call us and say, ‘My bottle’s empty! Let me go home now!’”

When Greg reached three years in remission, he made an appointment with the doctor who headed OMRF’s cancer section. “I asked him how long I was going to need to keep taking chemo,” Greg recalls. “He said, ‘We don’t know.’”

Of the 31 AML patients who’d enrolled in the OMRF study, only Greg and one other had survived. The doctor told Greg that no more than a few dozen AML patients worldwide had lived as long as Greg. “And he said that most of them were still taking the drugs.”

Still, Greg was ready to move on with his life. He decided to stop his treatments.

For the next two years, Greg visited OMRF regularly for follow-up testing. When he and the other patient both reached the five-year survival mark, the news made the Daily Oklahoman. The Tulsa World ran the story on the front page.

By then, Greg was 22. Once he’d ended chemotherapy, he’d transferred to Oklahoma State University, where he’d soon earn a degree in forestry and conservation. He’d also gotten married.

Although his fellow survivor would later suffer a recurrence that proved fatal, Greg remained cancer-free. He enjoyed a long career as a conservationist for the U.S. Department of Agriculture. That work took him to every corner of Oklahoma and as far away as Iraq. He earned an award from the U.S. State Department for helping organize farm cooperatives as part of the reconstruction effort in that war-torn country.

After a year of retirement in Owasso, where he now lives, he decided he missed his work. So now he’s back at it, splitting his time between jobs for the State of Oklahoma and the USDA.

OMRF closed the research hospital in 1976. The reason, as with so many decisions organizations make,

was money.

The hospital initially operated on a free care model, with OMRF obtaining grants from the National Institutes of Health to pay for patient expenses. But the NIH grants didn’t keep up with the ballooning costs of cancer care. OMRF started billing patients, but those fees—which began at $5 a day and only covered a portion of the costs—proved too little, too late.

Still, OMRF maintained its tradition of clinical research and patient care by opening a research clinic. As an outpatient clinic, it no longer maintained beds. That

meant there were no more overnight stays or long-term residents like Greg. In the increasingly expensive and competitive market for healthcare, large hospitals would meet those needs.

Instead, OMRF’s physicians would see patients who suffered from illnesses for which specialized care was not widely available and that were also being studied by OMRF researchers. This led to the creation of research clinics to treat Oklahomans suffering from autoimmune diseases like lupus, rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis.

Today, OMRF’s Multiple Sclerosis Center of Excellence and Rheumatology Research Clinic care for thousands of patients. Like Greg, many participate in clinical trials of experimental medications, gaining access to cutting-edge therapies before they’ve become available in hospitals and doctors’ offices. The information OMRF physicians gather from these and other studies, in turn, paves the way for better patient outcomes.

Indeed, this is what’s happened in AML.

Early studies like the one Greg was a part of saved only a precious few lives. Nevertheless, the findings from those clinical trials enabled researchers to develop a deeper understanding of the condition. That feedback loop steadily improved the quality of care and survival rate for patients suffering from leukemia.

Even now, chemotherapy remains the backbone of AML treatment regimens. Decades of experience have enabled physicians to refine their approaches, with better understood and more precisely refined dosing regimens. Also, since Greg’s diagnosis, researchers have figured out that AML is not a single disease but, rather, an umbrella that encompasses a group of sub-conditions. Depending on the specific subtype of a patient’s AML, doctors often supplement chemotherapy with other treatments, including radiation, a class of drugs known as targeted therapies, and stem-cell transplants.

Using these approaches, the prognosis for AML patients has improved. The five-year survival rate is now 27.4 percent for all patients, according to the American Cancer Society. While still low compared to many other cancers, it’s roughly ten-fold higher than it was 50 years ago, when Greg was diagnosed.

Young patients have seen the greatest leap forward. A 2015 study found a five-year survival rate of 36 percent for AML when first diagnosed between the ages of 19 and 30. In those, like Greg, where the disease was found at age 18 or younger, nearly half were alive a half-decade later.

While no one knows why Greg responded to and survived chemotherapy at OMRF when no one else in the study did, Prescott suspects his youth may have played a role. “Younger people do better with leukemia,” says OMRF’s president.

Researchers have identified a number of changes in the DNA and chromosomes commonly found in people suffering from leukemias. Some of these changes, or mutations, happen over a person’s lifetime as a sort of flaw in the aging process or due to exposure to radiation or cancer-causing chemicals. But in childhood leukemias, the mutations are often inherited from a parent.

“For young patients with a certain type of leukemia, the hypothesis is that the disease comes from a birth defect, a specific cancer stem cell or cells,” says Prescott. “That cell or group of cells is always there, and it keeps making new cancerous cells unless you kill it.”

Chemotherapy sometimes can do just that. “Destroy the cancer factory, and the disease stops.” Then, he says, “You can live your life.”

This past spring, Greg’s friends held a small party to mark his 50 years of living cancer-free. For Greg, the occasion brought back all sorts of memories. He recalled the arts and crafts area at OMRF, where a volunteer helped him make pots in between I.V. doses of chemotherapy. He remembered how his mother would cook him whatever meal he wanted when he finished a course of treatment. And he thought about the many other patients with leukemia he’d gotten to know during his years at OMRF. None had survived.

Yet Greg had enjoyed a full life. Like most, it had come with its share of peaks and valleys: marriage, fatherhood, divorce. He’s endured the pain of losing a son. He cherishes the joy his daughter and grandchildren have brought him.

He knew that every person in that long-ago clinical trial would have valued the chance to live as he had. To grow up. To have a family. To turn 67 and think, okay, what will tomorrow bring?

In a way, he realized, he was living for each of them.