Train the next generation of biomedical scientists and clinicians

In high school, Jang Kim kept looking for more. When he felt like the opportunities for learning and growth at Choctaw High were limited, he applied to and was accepted at the Oklahoma School of Science and Mathematics in Oklahoma City. At OSSM, he eventually recognized he wanted to broaden his scientific knowledge beyond the classroom. So, he talked to a teacher about a laboratory internship.

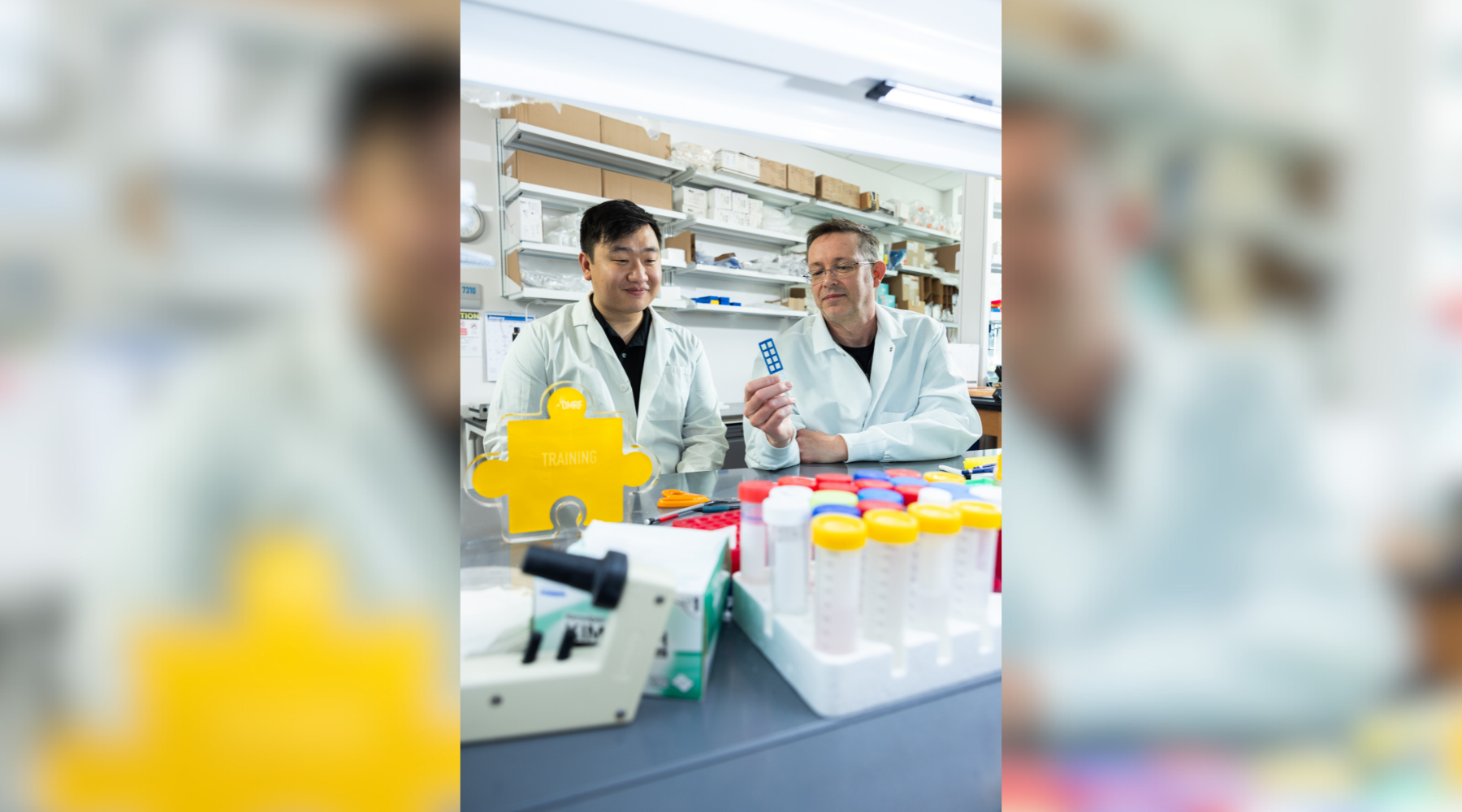

Down the street at OMRF, Dr. Lorin Olson had never hosted a high school student in his lab. Olson had come to the foundation a few years earlier after finishing a postdoctoral fellowship at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York. When Kim’s teacher reached out about an internship for his student, Olson said, “Sure, I’d be happy to help. Send him over.”

That was 2013. With the exception of a brief hiatus during Kim’s first year of college, he’s been a part of Olson’s lab ever since.

Kim, now a graduate student working on a Ph.D. under Olson’s mentorship, still remembers his first day in the lab. He used an instrument called a cryostat to embed tissue samples in a frozen block, then sliced through the block to create cross-sections for study under a microscope. From the get-go, he realized he’d found a different kind of scientific world than the one he’d encountered in classrooms. “It was much more intense and hands-on,” he says. And unlike lab classes in high school, there was no “follow the cookbook” recipe. The questions were open-ended, the answers yet to be determined. He was hooked.

Kim majored in chemical biosciences at the University of Oklahoma, and he continued his work in Olson’s lab, which culminated in a senior capstone project. That research led to a publication in a scientific journal, and for his contributions, Kim was listed as one of the authors. “Productivity in science is putting your name on new knowledge,” says Olson. “That’s what Jang got to do at a pretty early age.”

Still, after graduation, Kim found himself at a crossroads. He worked as a technician in Olson’s lab for two years before ultimately deciding to pursue a Ph.D. in cell biology at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center. Through an agreement with OU, graduate students can opt to study with an OMRF scientist (and 56 currently do). Kim chose Olson.

“Because of our previous history, I knew Lorin was a great mentor,” says Kim. “He’s really understanding.” If, for instance, Kim showed Olson “data that didn’t make sense,” Olson would guide Kim through what to do next.

At this, Olson – who’s been sitting alongside Kim – pipes up. “That’s how you know someone is ready for graduate school. They recognize when data sets don’t make sense.”

In the four-plus years since he began working toward his Ph.D., Kim has produced plenty of data that makes sense, and he’s on track to earn his doctorate in 2026. This past year, the National Institutes of Health awarded him a prestigious Ruth L. Kirschstein Predoctoral Fellowship, which will fund the final two years of his graduate studies. After that, he’ll likely take on a postdoctoral fellowship. While Olson values Kim’s many contributions to his laboratory’s work, he’s encouraging his protégé – as he did – to “leave the nest” and do his postdoctoral training elsewhere. “It’s a chance to go and live in a different city and experience a new part of life. And it’s an opportunity to learn new science from someone else.”

Kim listens, nodding, while his mentor offers this advice. This next big step, does it make him nervous? Or maybe excited? A moment passes, maybe two. “A little of both, I guess.”

He has time to figure it out. Until then, he’ll focus on his work in Olson’s lab. There, he’s studying proteins that help heal wounds and repair blood vessels. Specifically, he’s looking at how a change in a gene that controls these proteins can cause facial abnormalities in people with this genetic mutation. The research could not only point to ways to prevent the abnormalities, but it could also shed important light on heart disease and cancer.

That, along with taking care of his pets – Tiki, an orange tabby cat, and Prim, his goldendoodle – will fill his days and nights. It’s a focused existence, and that single-mindedness is a trait Kim shares with his mentor. “We’re both able to maintain interest in one thing for a long, long time,” says Olson.

Finding kindred spirits like Kim, says Olson, is one of the many reasons he enjoys mentoring students. It reminds him of the community around a favorite hobby: playing the fantasy game Dungeons & Dragons. “We’re all nerding out over the same thing, and it’s a thing that no one else understands.”