Provide science-driven, compassionate care

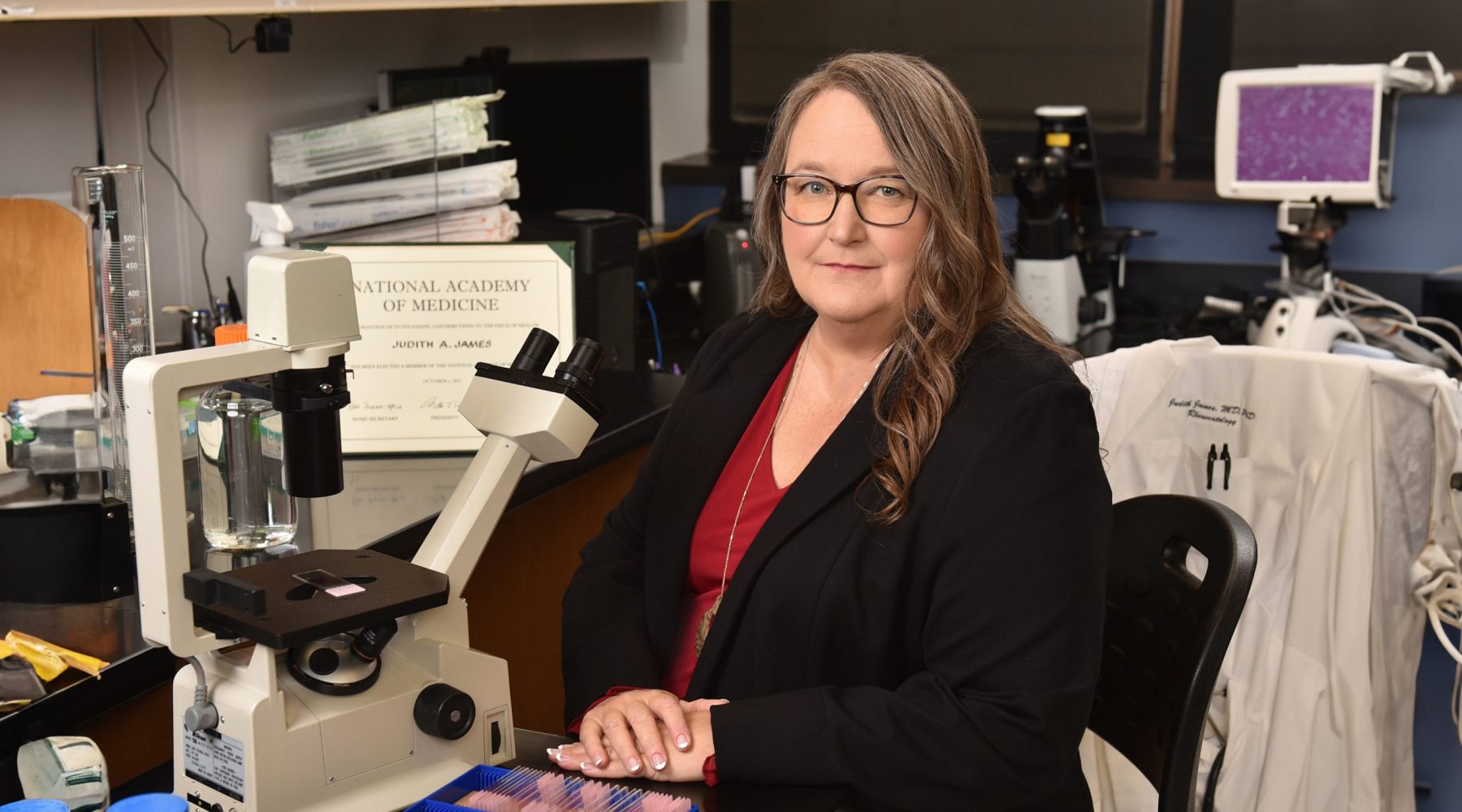

For Dr. Judith James and the staff of OMRF’s Rheumatology and Multiple Sclerosis Centers of Excellence, providing care is all about relationships. “I’ve taken care of some patients for more than 30 years,” says James. In some cases, that caregiving relationship now stretches across multiple generations of the same family. “I like that partnership,” she says.

A rheumatologist and immunologist, James is one of the world’s leading experts in understanding and treating autoimmune diseases. This category of illness, which includes lupus, multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis, encompasses more than 80 conditions that, together, affect an estimated 25 million Americans. Severity, organs and bodily systems impacted vary, but all autoimmune diseases share a central feature: They develop when the body’s immune system mistakes its own cells for invaders and begins attacking them.

James’ practice at OMRF is devoted to treating patients with these diseases. Because many of the conditions have symptoms that overlap – indeed, it is not uncommon for people to live simultaneously with multiple autoimmune illnesses – understanding an individual patient’s situation is crucial. For that, James begins at the source.

“I sit with the patient and say, ‘Tell me the first thing that went wrong,’” she says. From there, she lets patients unfold their own stories. James prompts them with occasional questions and requests for clarification, but she’s careful to let her patients be her guide, not vice versa. “Each person perceives their symptoms in different ways,” she says.

As she listens, she thinks about what patients are describing. She performs a physical examination. And she orders a specialized battery of clinical tests that foundation scientists have developed over decades of studying autoimmune diseases.

These tests, which look for certain telltale proteins – many discovered by OMRF scientists, including James – provide critical information to help pinpoint a patient’s condition. But that, says James, only represents a piece of the puzzle.

“When I started practicing, I thought it was all about solving the mystery, about finding the diagnosis,” she says. But for her patients, a diagnosis is far from an endpoint, as many autoimmune diseases lack effective courses of treatment.

Still, the therapeutic landscape has improved dramatically over the past two decades. OMRF has played a key role in these advances, performing clinical trials for nearly every new therapy for multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis and lupus that has reached hospitals and clinics during that time. In the process, James and her colleagues have refined how they approach those trials, due in no small part to a grant from the National Institutes of Health

that came with a designation for OMRF as one of

only a handful of the nation’s Autoimmunity Centers of Excellence.

“Almost all traditional clinical trials study whether a medicine works or doesn’t,” says James, who holds the Lou C. Kerr Endowed Chair in Medical Research and serves as OMRF’s executive vice president and chief medical officer. With the federal grant, which OMRF first received in 2009 and has since been renewed three times, including in 2024, James and her fellow OMRF scientists have delved deeper. “We try to understand why a medication works or doesn’t, and which patients should be enrolled in a trial for a particular therapy,” she says. This kind of probing clinical research enables her to practice what she calls “science-guided medicine,” using “cutting-edge information from studies to manage the care” of patients for whom

the standard treatment playbook holds no answers.

For James, that’s allowed her to pioneer novel concepts, like stopping medications for lupus

patients whose symptoms have stabilized. Her work has found that many can safely halt a standard course of therapy. She also devised a method to identify those who should.

She also led the first prevention trial for lupus, using clinical testing born at OMRF to identify people at risk of developing the disease. Then, she and other OMRF caregivers administered a medication that might stop the onset of lupus. They’ve also participated in a similar study for rheumatoid arthritis.

James knows not every approach will succeed. Still, she says, “We can learn a lot even when a drug fails.”

As a researcher, she knows progress can be halting, coming in fits and starts. Yet as a physician, she knows that time is a luxury her patients often

don’t have.

Their daily struggles, she says, serve as a constant inspiration. “It pushes us to do better science.”