Foster a collegial and collaborative environment that celebrates innovation and the sharing of ideas

A scientific collaboration is not a marriage. But that doesn’t mean the two relationships don’t share some important traits.

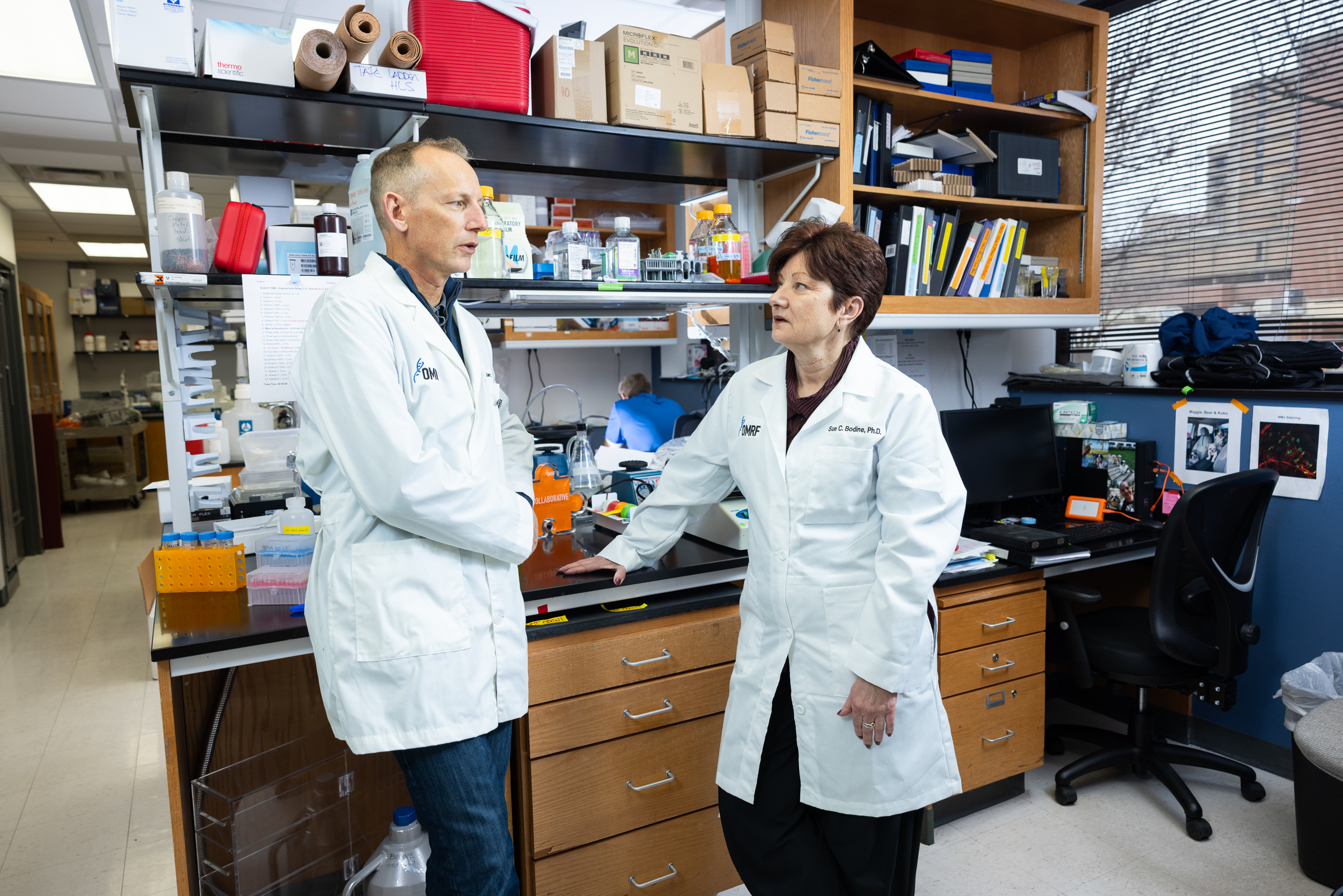

In both, says Dr. Sue Bodine, “Communication is vital.” As is another factor: “mutual respect.”

Bodine should know. Throughout her career, she’s maintained a series of successful scientific partnerships. One of the most important has been with Dr. Benjamin Miller, with whom she’s been teaming up for a decade.

The two study muscle loss that accompanies aging. They have the same goal: finding novel strategies to slow that process. However, each brings a different skill set to the table. Bodine’s lab specializes in protein breakdown, while Miller’s focuses on synthesizing proteins. That balance matters, says Miller.

“You look for people who have strengths you don’t,” he says. “You want somebody who complements what you do.”

The pair met while serving as volunteer editors for the Journal of Applied Physiology. Miller invited Bodine, then a professor at the University of California, Davis, to give a lecture at Colorado State University, where he was a faculty member. They hit it off and soon mapped out their first joint project.

Although they displayed a similar commitment to the work, they didn’t always find common ground. And that, says Bodine, was just fine. “For a collaboration to work, you have to be open to differences of opinion. You need to be able to discuss your disagreements.”

This was critical because the tandem’s work was challenging a core belief in the field – that muscles produce less protein as they age. In fact, they showed muscles actually produce more protein; it’s just that the protein is degraded, shunted off to biological scrap heaps rather than building muscle mass.

Miller eventually moved his laboratory to OMRF, where he now holds the G.T. Blankenship Chair in Aging Research and leads the foundation’s Aging & Metabolism Research Program. In 2023, Bodine joined him, opening a lab around the corner from Miller’s.

That proximity, says Miller, has strengthened their work together. “Our offices are next to each other. We can just pop in the door and ask a question.” Bodine agrees. “It’s the informal stuff; those daily interactions make a big difference.”

Just as important, says Miller, is the broader environment OMRF has created, which encourages researchers to pool their talents. “It’s an open-door place.” While many institutions may talk about “team science,” says Miller, that commitment is real at OMRF. “I have never knocked on a door and not found someone willing to help.”

In a scientific world where problems are increasingly complex, that cooperative spirit is essential, says Bodine. “You can’t be an expert in everything. You have to rely on other people.”

In 2024, she and Miller teamed up to secure a portion of a $7.7 million grant from the National Institutes of Health. Working with researchers from the Florida Institute for Human & Machine Cognition and the University of Florida, they’ll conduct a clinical trial examining why some people respond better to strength training, while others do better with endurance exercise. Their ultimate aim, says Miller, is to create a predictive model that will allow them to “modify exercise plans for different types of people, so that, hopefully, everyone has a positive response.”

Bodine is optimistic that the project will yield useful new insights. She’s also excited to continue her partnership with Miller. “We both have pretty rigorous scientific standards. And we’re both willing to challenge the dogma.” Plus, she says, “I really enjoy working with him.” If the past is any predictor, there will be more joint efforts to come.