An Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation physician-scientist has long theorized there’s more than a casual association between the autoimmune disease lupus and one of the world’s most common viruses.

A new scientific discovery has confirmed her theory.

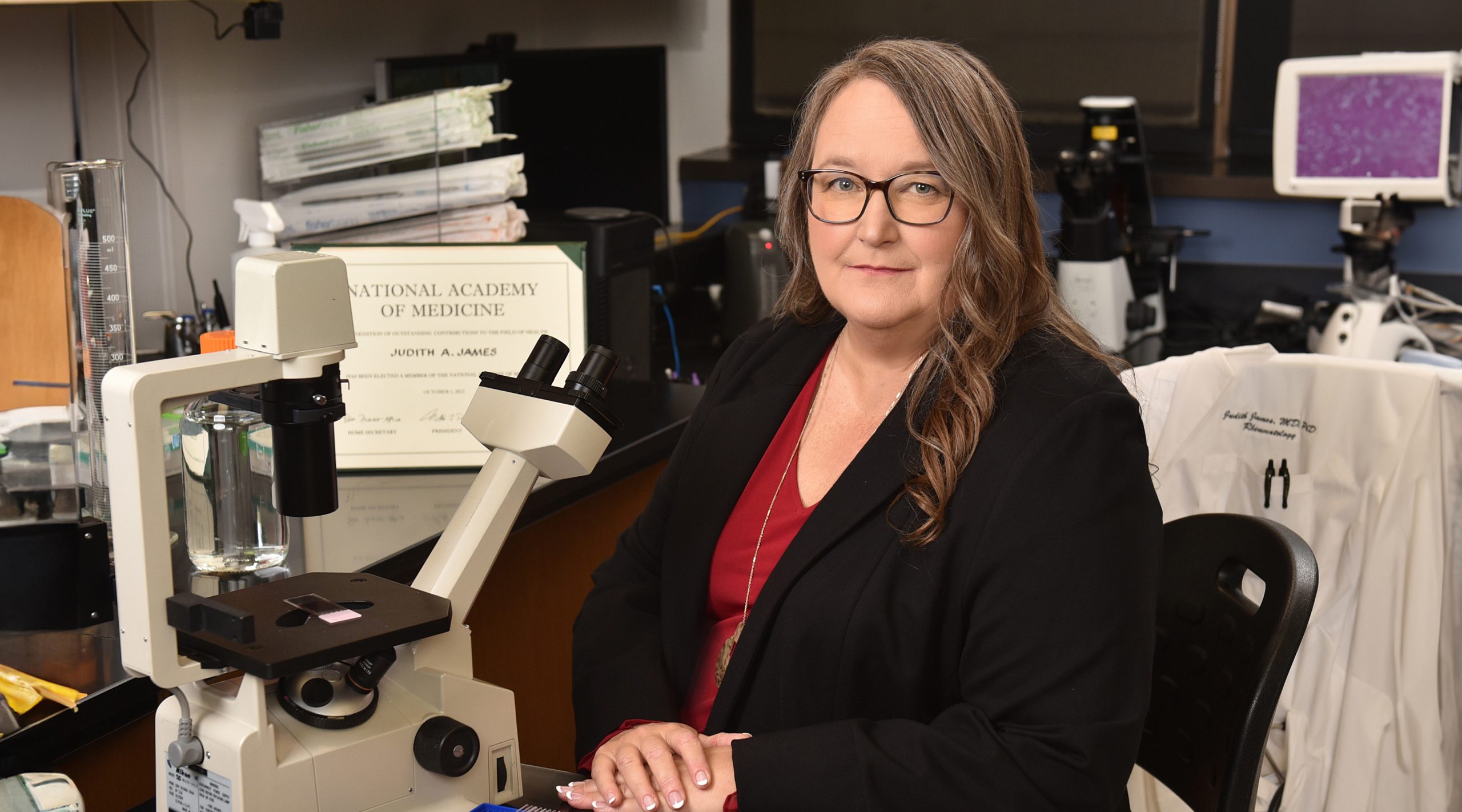

OMRF’s executive vice president and chief medical officer, Judith James, M.D., Ph.D., contributed to a Stanford University study that found the Epstein-Barr virus, or EBV, drives autoimmunity in people with lupus. The breakthrough was published Thursday in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

“This discovery changes the way the field thinks about EBV and lupus,” said James, who holds the Lou C. Kerr Endowed Chair in Biomedical Research at OMRF. “It opens the door to precise lupus treatments that target specific immune cells instead of suppressing the entire immune system.”

Lupus is a chronic disease that can cause inflammation and pain throughout the body. It affects an estimated 1.5 million Americans, about 90% of whom are women. Scientists have long known lupus has a strong genetic component, but environmental triggers are necessary to activate the disease.

The Epstein-Barr virus infects nine of 10 people by adulthood. It can cause mononucleosis, but most people experience either minor cold-like symptoms or none at all. Once a person is infected, the virus remains dormant in the body for life. The virus can occasionally reactivate, and previous research has shown this happens more frequently in with lupus, especially those whose disease is active.

In this study, researchers found that EBV directly infects and reprograms a type of immune cell called B cells. A small and usually harmless number of these reprogrammed B cells can be found in healthy people, but in people with autoimmune diseases like lupus and multiple sclerosis, they attack the body’s healthy tissue instead of foreign invaders.

The results surprised James’ longtime collaborator, Stanford physician-scientist William Robinson, M.D., Ph.D., who led the study.

“We never expected EBV to directly change specific B cells themselves,” Robinson said. “Knowing this gives us a chance to remove the root cause of lupus: these EBV-infected driver cells.”

James said an early-stage clinical trial developed at OMRF is pending on an approach to inhibit EBV. Also in development are other small molecules that aim to decrease EBV reactivation.

Currently, lupus is treated primarily with steroids or with drugs that broadly suppress the immune system. The danger, James said, is that these global immunosuppressants leave people vulnerable to infection and possibly even to cancer.

If successful, new therapies or vaccines could potentially prevent the onset or progression of lupus. “For that reason, this discovery looks like a game-changer,” James said.

You can read the entire journal article here.