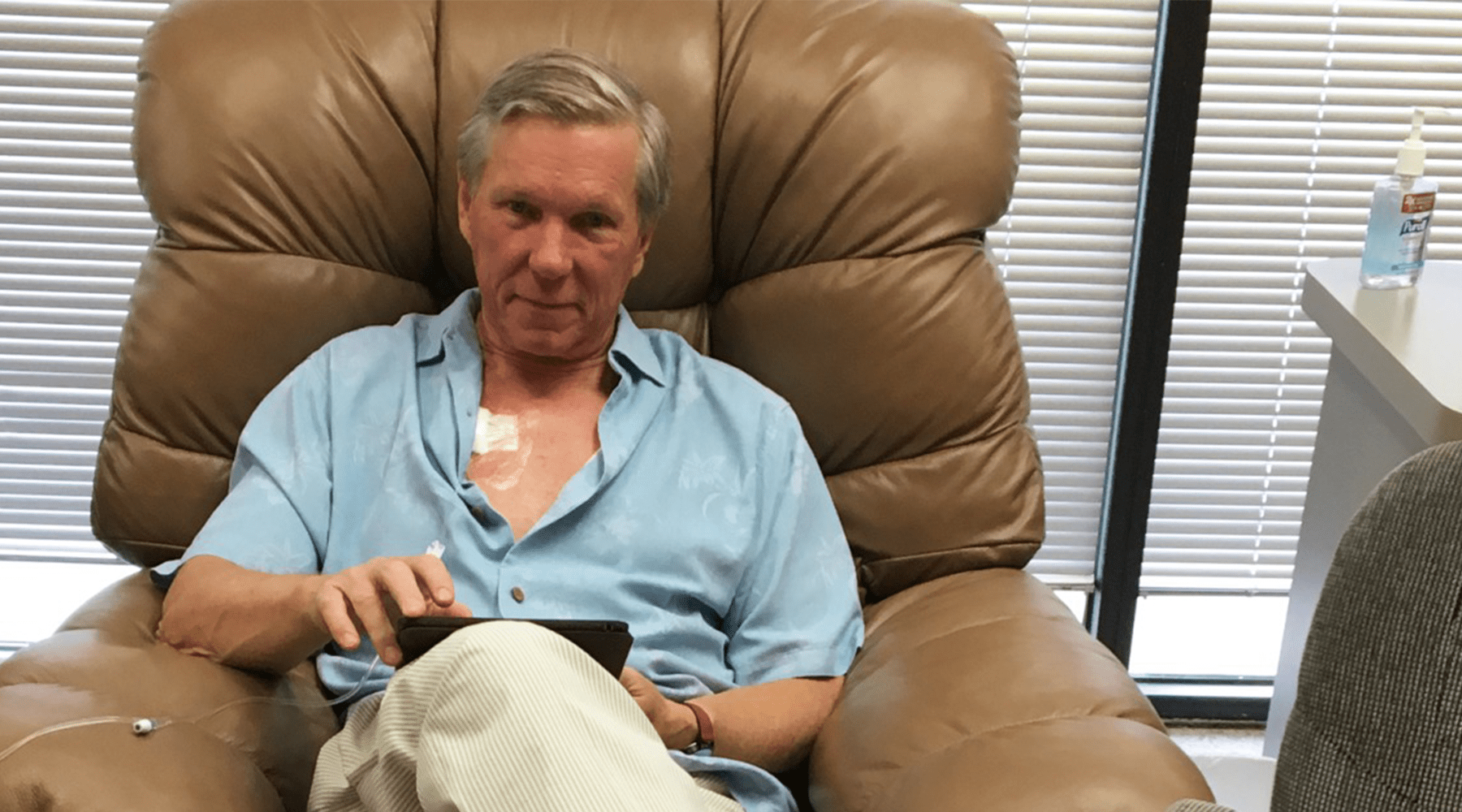

A little more than three years ago, I was diagnosed with urothelial cancer. The prognosis was grim, and I thought I’d be lucky to make it to the end of the year.

Well, here I still am.

The ride has been longer and wilder than I could have imagined: chemotherapy, surgery, immune therapy, metastasis, hair loss, nausea, weight loss, neuropathy, fatigue, uncountable numbers of visits to doctors, and scans, scans and more scans. By early this year, I thought I’d seen it all.

Then came the coronavirus.

I had just finished a(nother) course of chemotherapy, which tends to lay waste to a person’s immune system. Even though I was receiving drugs to help counteract these effects, I was presumed to be at high risk for the newly emerging virus.

So, I faced an unenviable choice. I could put myself at risk for viral infection by continuing my cancer treatment, where I’d face the chance of being exposed at healthcare facilities. Or I could self-isolate and suspend my treatment, which would lessen my odds of SARS-CoV-2 infection but leave me prone to cancer that, despite my physicians’ best efforts, remained with me.

I was hardly alone in this dilemma. Everywhere, people suffering from chronic health conditions faced similar devil-or-the-deep-blue-sea decisions.

In a study published in May in The New England Journal of Medicine, Kaiser Permanente reported a drop of nearly 50 percent in heart attack admissions in its Northern California hospitals. Around the same time, the insurer Cigna reviewed claim and pre-authorization data for seven conditions, they found declines in hospitalization rates ranging from 11 percent for acute coronary syndromes to 35 percent for atrial fibrillation.

This mirrored larger trends. The Centers for Disease Control compared emergency room visits during the early part of the pandemic to the same period last year, and it found a 42 percent drop-off.

Does that mean people have gotten healthier? Almost certainly not. Too frightened by the pandemic to seek care, many opted to let dangerous conditions go untreated. But that’s a state of affairs that can only go on so long.

When their illnesses finally leave them no choice but to seek treatment, they’re “presenting late with strokes and heart attacks,” the chief medical officer for a major medical center told The New York Times. “Or they’re not showing up until they can barely breathe from heart failure.”

In April, emergency medical services teams in Newark made four times the number of on-scene death pronouncements as during that same month in 2019. Covid-19 accounted for fewer than half of those new deaths.

The statistics and anecdotes tell a stark tale. Conditions ignored and care delayed doesn’t heal people. It simply leads to more death and disability tomorrow.

I made the choice to continue my course of cancer therapy. I was fortunate, in that my oncologist was not located in a hospital. So, I did not feel the same degree of peril I might have if my care required me to be treated among patients suffering from Covid-19 and other communicable illnesses.

Still, as we all know, the virus lurks anywhere there are people. So, physical distancing and mask-wearing measures were immediately enforced. I couldn’t enter without having my temperature taken and answering a battery of questions. Visitors were banned.

These measures were necessary, and they helped protect patients and made us feel safe. But they also stripped away a support system that many of us relied on: family and friends.

Even when you’re a physician and medical researcher, being a patient is frightening and disorienting. Having someone by your side, to ask questions of the doctor, or simply to hold your hand, can make all the difference. Read more: “My Cancer Journey,” by Dr. Stephen Prescott

For me, the therapies I’ve received during these past five months have helped keep my cancer at bay. Recently, I’ve begun to feel strong enough that I’ve considered returning onsite to work at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation (where our scientific staff and many others have continued their duties in spite of the pandemic). I’ll even volunteer to go grocery shopping or run other errands. But my wife, Susan, remains cautious.

“Let me do that,” she says. “You don’t need to go out.” And she’s right.

“Let me do that,” she says. “You don’t need to go out.” And she’s right.

Last month, I began receiving a new experimental therapy at the Stephenson Cancer Center. I’m excited for the opportunity to benefit from this novel drug. Still, I can’t help but wonder how many other promising treatments have been stalled in the pipeline by this health crisis.

Those therapies will reach patients eventually. In the meantime, though, many won’t receive those drugs at the moment they most needed them.

That delay will come with a price. Because when it comes to fighting disease, time is one commodity we can never reclaim.

—

Get Dr. Prescott’s column delivered to your inbox each Sunday — sign up here.