What follows may qualify as two of the least surprising statements you’ll read in a while. People are pretty tired of everything related to the coronavirus. And they’re yearning for some news — really, any news — that will brighten their days.

As someone who’s devoted every column since (checking Word files …) March 15 to the virus, I am firmly in both camps. So, this week, let’s take a little detour that will, I hope, check both of the above-mentioned boxes.

The narrative begins in Waynoka, a small farming community in western Oklahoma. That’s where the Jaquith family settled around the time of the Land Run of 1893.

The family farmed the same plot of land for generations. Born in 1941, Gerald Jaquith grew up on the land, helping his father to grow wheat and raise cattle. Sometimes, they’d hunt deer together in the wooded areas that run along the Cimarron River.

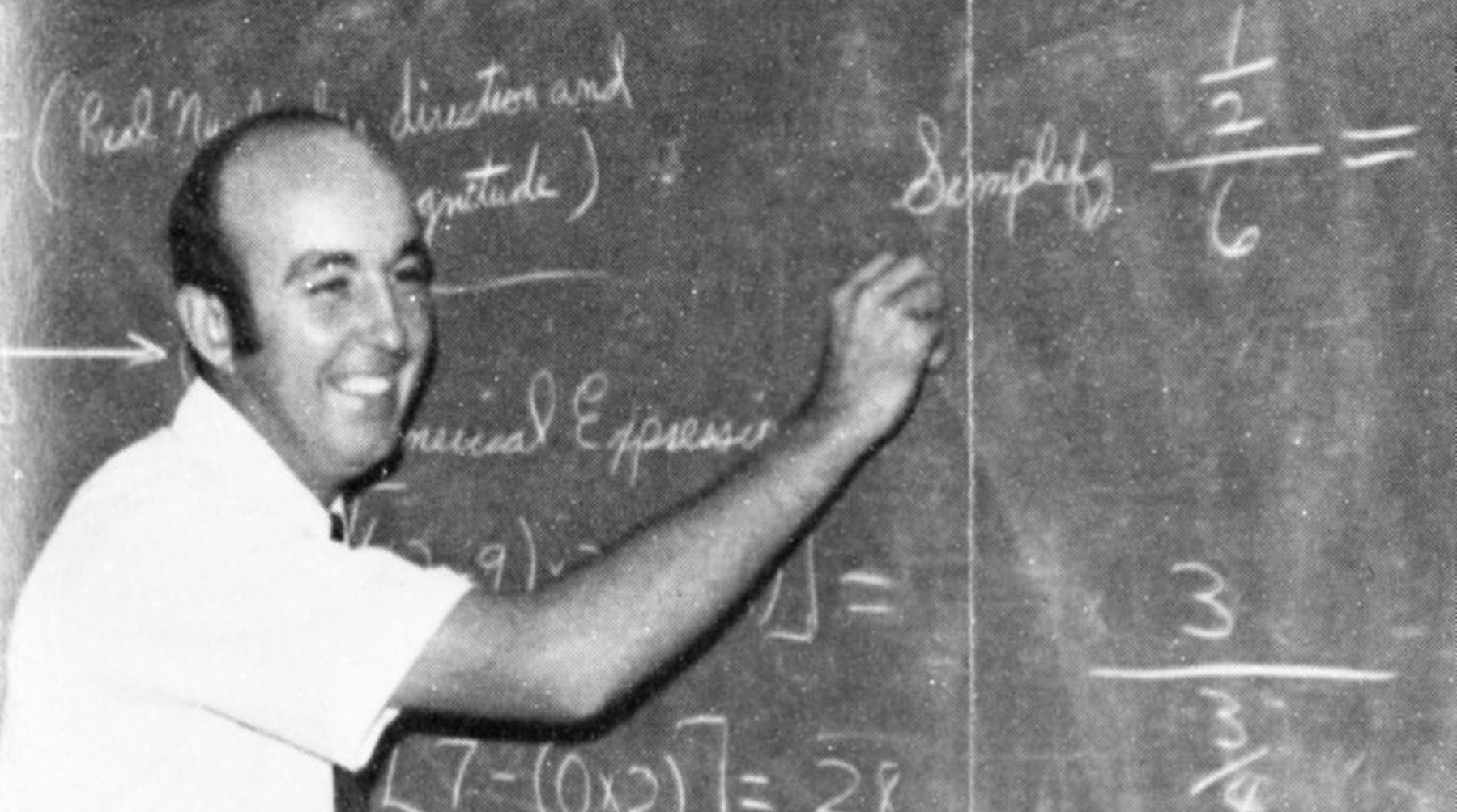

Gerald went away to college, then spent the next two decades teaching high school math in New Mexico and Texas. When his father died of heart disease in 1984, he returned to Waynoka to help his mother run the nearly 1,000-acre farm.

Still, Gerald loved teaching math, and he continued to do so at Shattuck and Ringwood High Schools. There, he encouraged his charges to do as he had done, to look beyond their own backyards when it came time to choose a college. Explore the world, he urged them. And many did.

After Gerald’s mother passed away, also of heart disease, he retired from teaching. With the help of his friend Mark Dickinson, he kept tending the farm. Gerald, said Dickinson, was “a good-natured, everyday kind of person, the type of guy who would stop to help someone broken down on the side of the road.” If he did, he was probably driving his old Ford truck, which he bought in 1986 and kept running for the next 33 years.

Last summer, Gerald died in an accident on his farm. He was 78.

During his life, he’d made regular gifts to the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation. Some had been as small as $5. Over 33 years, they totaled $7,500. That’s a significant sum, especially for a retired high school teacher. Yet they didn’t hint at the generosity he’d show OMRF upon his death.

His attorney, John Meinders, informed us that Gerald had left his entire estate to OMRF. That estate, which included his farm as well as his retirement savings, totaled more than $2 million. We were stunned.

When we visited Gerald’s farm, we found the remains of a life lived simply and frugally: Tinkerbell, the dwarf cow with a crippled leg he’d decided to keep as a pet; a collection of family photos; a barn full of farm equipment. And atop a stack of documents and neatly folded new coveralls on the kitchen table of his tiny farmhouse, a copy of OMRF’s 2015 annual report.

Meinders doesn’t know why his client chose OMRF as the beneficiary of his will, but he suspects it was because Gerald lost both parents and his brother to heart disease. “Gerald was a man with vision and a strict set of values,” said Meinders. “He always wanted to help other people.”

At OMRF, his gift will support research into diseases that touch the lives of Oklahomans and people everywhere. Our goal, as always, will be to translate that generosity into discoveries that improve the lives of patients suffering from illnesses like cancer, Alzheimer’s and heart disease.

To honor Gerald’s gift, we’ll name a lab in his memory in our cardiovascular biology program, where scientists probe the diseases that claimed the lives of his family members.

We were set to announce Gerald’s gift in early March, but with the onset of the pandemic, we tabled it until a more appropriate time. As new virus cases ebb and society now inches back toward normalcy, we decided that time had finally come.

When we released the news early last week, we were stunned. Again, in a good way.